Five years on, summit aims to breathe life into Paris deal

Five years ago, countries agreed a plan to chart humanity's path away from climate catastrophe, with the landmark Paris Agreement paving the way to a greener, healthier future.

Yet carbon pollution has continued its steady rise as temperature records tumble with increasing regularity.

Following a year of raging wildfires and record megastorms, heads of state will this week seek to breathe new life into the Paris Agreement.

On December 12, 2015, after 13 days of grueling negotiations between 195 country delegations, the gavel came down on the COP 21 conference with a momentous message.

Nearly every nation on Earth committed to limiting warming to "well below" 2 C above preindustrial levels.

A more ambitious cap of 1.5 C was also adopted.

But things have not gone to plan.

Its viability questioned by Donald Trump's decision to withdraw the US and a collective failure to enact its pledges, the Paris deal's goals are currently set to be missed.

The last five years have been punctuated by ever-growing alarm from scientists highlighting the need for urgency, and by popular anger manifested in millions-strong youth strikes for climate.

But despite the hard data and hardening public opinion, "climate policies have yet to rise to the challenge," said United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

"Today, we are at 1.2 degrees of warming and already witnessing unprecedented climate extremes and volatility in every region and on every continent," he said on December 2.

Such warming is already contributing to the rash of wildfires that tore across California and Australia in 2020, as well as the record-breaking number of Atlantic hurricanes and tropical storms.

Limited progress

Despite its shortcomings, the Paris Agreement is probably already limiting the damage of otherwise unchecked climate change.

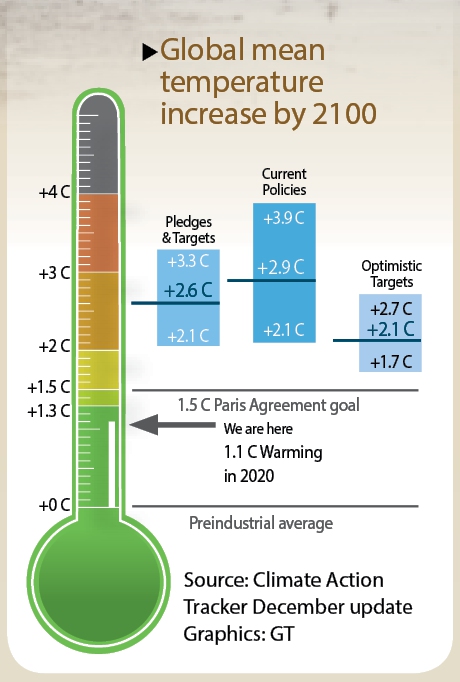

"Before the Paris Agreement, we were headed for a warming of anywhere between 4 C and 6 C by the end of the century," said Christiana Figueres, who was UN climate envoy during COP 21.

She said the first raft of country promises - termed Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) - set Earth on course to be 3.7 C hotter by 2100.

"Obviously 3.7 is way, way too much and unacceptable," she said in an online press conference. But 2020 has seen a slew of major economies commit to achieving net-zero emissions sometime in the future.

Climate Action Tracker calculated on December 1 that with Japan, South Korea and the EU aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050 and China by 2060 - coupled with Joe Biden in the White House - warming could be limited this century to 2.1 C.

So far more than 100 nations accounting for the majority of carbon emissions have unveiled plans for net-zero.

"It's positive, the question is: Will it happen?" said COP 21 President Laurent Fabius.

The situation is likely to be helped by events of 2020, with the economic slowdown linked to the pandemic likely to result in a roughly 7 percent fall in emissions compared with 2019.

But the UN has sounded the alarm over countries' spending on sectors dependent on fossil fuels to power their COVID-19 recoveries.

Under Paris' "ratchet" mechanism, nations must increase their emission cutting plans every five years.

With days remaining before the December 31 deadline, fewer than 20 nations accounting for 5 percent of emissions have so far submitted revised NDCs.

Organizers of this weekend's virtual climate summit - held online in lieu of COP26, which has been delayed until November 2021 due to the pandemic - express hope it can drum up renewed momentum for stricter pollution curbs.

Torrential rain in Italy's Calabria Region causes severe flooding in the provinces of Crotone and Cosenza, resulting in widespread damage on November 21. The regional government has requested a state of emergency. Photo: VCG

'We still have time'

Mohamed Nasheed, former Maldives president and an ambassador for the Climate Vulnerable Forum representing 48 countries at the highest risk from climate change, said the summit needed to result in "much higher ambition in terms of each country's plans for reducing emissions."

"Our nations, particularly the small island states, will be condemned to extinction even with a two degrees outcome," he told AFP.

"Anything less than 1.5 C condemns us to death."

High-risk nations have continually called for rich counterparts to make good on a promise to provide $100 billion annually to help them adapt to climate change.

But even with renewed ambition - and if the adaptation funding ever materializes - is it still possible to cap warming at 1.5 C?

"If all countries reach carbon neutrality by 2050, it's physically possible," said climatologist Corinne le Quere.

"But is it politically and economically possible?"

The UN estimates that to keep 1.5 C in play emissions must fall 7.6 percent annually throughout the 2020's.

That may well happen in 2020, but Le Quere told AFP that "a rebound is inevitable."

The UN's climate chief Patricia Espinosa, in a speech in November, summed up the state of play for climate action.

"What we don't know is the date it becomes too late, when we finally cross the point of no return," she told attendees of an online conference.

"What we do know is that right now, today, we still have time."

Newspaper headline: Warming expectations