Year-end: Chinese business in India

By GT staff reporters Source: Global Times Published: 2020/12/8 20:08:40

A bumpy 2020 with uncertainty ahead

Two women who often post videos on video-sharing app TikTok, shoot a video on a miniature cooking inside their house in Mumbai, India on July 1. Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:In April, India amended its FDI policy, widely deemed as a firing shot against Chinese investment amid downward spiraling bilateral relations. Since then, New Delhi has intensified its push for an economic decoupling with Beijing, banning hundreds of Chinese apps including TikTok and WeChat, while reportedly delaying the clearance of Chinese goods at Indian ports. Now, after half a year, how is Chinese investment in India? The Global Times spoke with several Chinese entrepreneurs in India, trying to present a through picture of their bumpy roads of doing business there. This is the first of a four-part special year-end review by the Global Times' biz team.

The year of 2020 has been a tough year for Wan Tao (pseudonym), a Chinese tech entrepreneur who had spent three years investing and researching India's fintech industry.

"I have thought of failure in India because of the fallout of COVID-19 pandemic, but grounding the investment plan due to local government's hostile policy was something I did not expect," Wan told the Global Times on Monday.

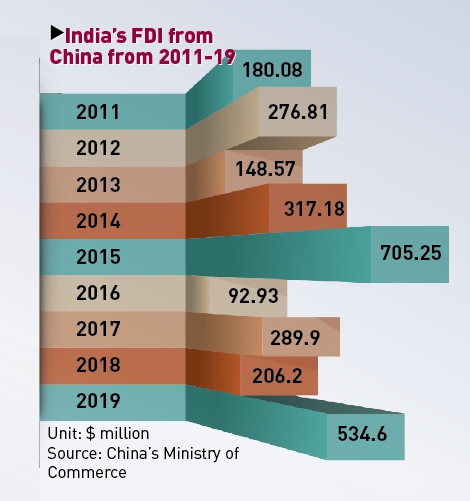

In April, India amended its policy on foreign direct investment (FDI), requiring any investment from bordering countries to go through a government approval process. As China is the only neighbor with significant trade relations with India, the move is widely seen as one made to limit Chinese investment.

Wan described this recent policy as a "straw that broke the camel's back" dragging his business into bankruptcy.

"Our liquidity evaporated, and we were unable to survive any longer. So, I made the ultimate decision to dissolve the Indian team and quit the market," Wan said, he was unwilling to discuss the process in detail.

Wan's experience is just the tip of iceberg reflecting how Chinese business endeavors in India has undergone transformation over the course of 2020 on the heels of a China-India border dispute. Navigating these new circumstances, some Chinese entrepreneurs - most in the internet industry - were unable to endure, while others, in particular in the manufacturing industry, had already bottomed out from the "darkest hours."

During a series of interviews conducted by the Global Times, Chinese entrepreneurs - who had closely linked their future prospects to the direction of China-India relations, remained cool-headed and somewhat pessimistic on the Indian market.

"Even if the two sides reach an agreement that prevents bilateral relations from deteriorating further, the Indian market won't be as open to Chinese investors as one or two years ago," Scott Wang, head of a China-invested fintech provider based in Gurgaon, India, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

As geopolitical factors add up uncertainty, some businesses are considering shifting focus from the South Asian market to other emerging markets, including Southeast Asia or Africa.

Graphics: GT

Waning internet business

In June, the Indian government abruptly banned 59 apps developed by Chinese firms, including the popular TikTok and WeChat platforms, claiming those apps were engaging in activities that threatened the "national security and defense of India, and impinge upon the sovereignty and integrity of India."

Since then, the Indian government has issued another three rounds of bans targeting at other popular Chinese apps, including popular gaming platform PUBG as well as Baidu, China's largest search engine provider. So far, around 267 Chinese apps have been banned in the world's second-largest internet market.

A Chinese business insider, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told the Global Times on Monday that most Chinese internet start-ups in India have frozen operations in India, with some already mulling over plans to withdraw from the market entirely.

Scott Wang noted that his fintech business had been in limbo for two to three months after the amended FDI policy in April.

"Despite strong performance over last few months, uncertainty is still increasing," Wang said, noting that his investment in India has become more "conservative" than last year, and that he has been considering shifting his business to Africa.

Around 70-80 percent of foreign investment firms in India's fintech sector are from China. According to Wang, some leading players in the industry are increasingly unwilling to shoulder the risk, and may look to exit.

Shunwei Capital, the Chinese venture firm established by Lei Jun, CEO, and Chairman of China's technology giant Xiaomi, told the Global Times that the firm is not focused on Indian projects "at the moment." Shunwei has already invested in several Indian apps including social media platform ShareChat.

Ant Group, the financial arm of Chinese tech behemoth Alibaba, is reportedly considering selling its 30 percent stake in Indian digital payment processor Paytm amid tensions between the two Asian neighbors. Ant Group refused to comment on the matter when contacted by the Global Times.

UC Web, a web browser subsidiary owned by Alibaba which was among the first batch of 59 apps banned by the New Delhi, suspended operations in India in August after entering the market a decade ago. Other apps that were on the list have reportedly considered similar moves, with many laying off local Indian employees.

Manufacturing bounce-back

While the internet industry maybe the first to feel the pain of stained bilateral ties, many Chinese manufactures have seen rapid business bounce back in India in recent months after a dive.

"Our operations ground to a halt for a few months in the first half of the year following the pandemic outbreak. And intensifying tensions between the two countries due to the border standoff also made our Indian clients hesitant to place orders," Xi Ting, Head of a Chinese-backed new-energy firm in India who has been working there for years, told the Global Times.

But in the second half of the year, Xi's businesses quickly resumed with more orders coming in.

"More orders from Indian clients were placed through us over our rivals from the US and Europe because the quick recovery of China's supply chain under effective anti-epidemic measures," Xi said, who believed that business conditions will continue to improve next year. And he plans to increase its local employment to 40-50 percent of its total staff in India next year.

Xi's story is not unique. In fact, it reveals a fatal flaw in the Modi government's plan to restrict Chinese investment aimed at boosting the local manufacturing industry: Local Indian manufactures are still heavily dependent on Chinese investment and are voting with their feet.

An executive of a leading Chinese smartphone marker, who prefers not to be identified, told the Global Times that the impact of Indian government's crackdown on Chinese enterprises has "not generated any impact" on their sales in India.

In the third quarter of 2020, four Chinese smartphone vendors - Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo and Realme - made up an overwhelming market share of 64 percent in the Indian market, according to a report by consulting firm Counterpoint.

"The development of industrial infrastructure is a long-term process that cannot be completed in one go. China has the world's most complete smart phone production chain which is irreplaceable," the executive said.

However, it is abundantly clear that India's anti-China policy has sent Chinese business confidence in the country into freefall.

When asked about future expansion plans, the executive from the leading smartphone brand only noted that the company will "continue its current business in India."

Li, head of a Chinese firm involved in an adjacent business connected to a major smartphone brand in India, told the Global Times that he will take a wait-and-see attitude about when it comes to investment depending on whether the current climate improves.

"Folks around me have turned their eyes from India to the Southeast Asian countries," Li added.

"We used to call India a promising 'blue sea,' but now it is pool full of uncertainty and unpredictability," the business insider told the Global Times.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Posted in: ECONOMY