US cities look to co-living to ease housing crisis

Source: Reuters Published: 2020/12/16 19:33:40

When teacher Ashley Johnson arrived in Atlanta after a cross-country move in 2019, she was quickly confronted with the city's affordable housing shortage, one of the worst in the country.

A friend told her about a service called PadSplit, which connects tenants with shared housing options, similar to boarding houses and a growing trend in the US.

For $145 a week, including utilities - far less than an apartment would have cost her - Johnson found a room in a house with four other housemates, just minutes from her work, with a furnished bedroom, and shared bathroom, kitchen and living room.

Five months later, she was able to move out. "It gave me time to save enough money to get my own housing," Johnson, 30, told Reuters by phone.

Informal shared housing - when someone finds roommates and splits the cost of an apartment - remains a key way for young people to move to urban areas and join the workforce.

Formal shared housing - also known as co-living when it refers to tenants from higher income levels - differs in that a specialized firm vets applicants and typically deals with utility bills so tenants have just one monthly payment.

The rise of this type of housing has also allowed companies to construct or refurbish buildings specifically for this use.

The idea is not a new one but it is resurging in US cities as both residents and housing providers grapple with an ongoing shortage of affordable units.

Nearly half of realtors reported seeing an increase in "group-living" in 2019, according to the National Association of Realtors.

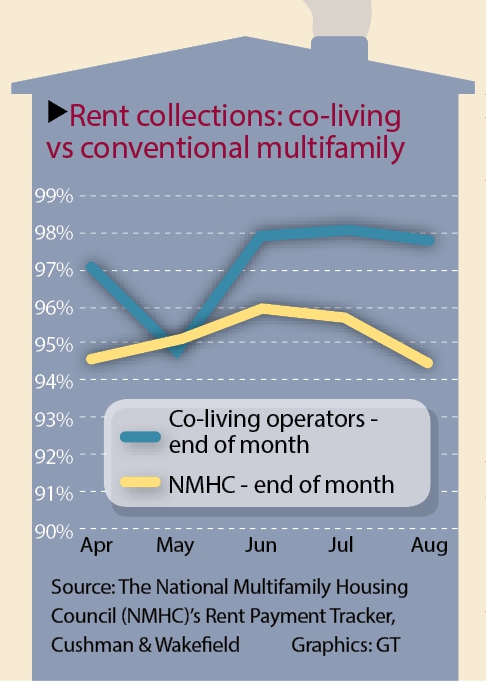

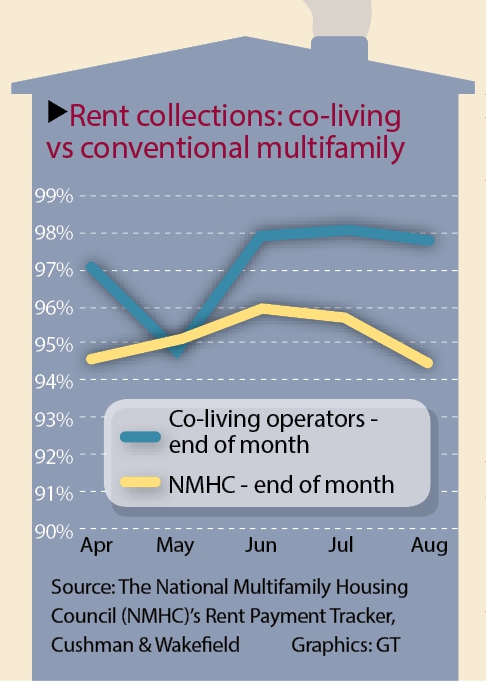

And that trend does not appear to have been slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the potential implications of an airborne virus for shared housing.

By the end of the second quarter of 2020, there were about 8,000 co-living "beds" in the US, with more than 54,000 more under development, according to a November report from real estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield.

Such options are up to 30 percent cheaper than studio apartments, the report found.

That does not surprise PadSplit founder Atticus LeBlanc, whose company focuses on tenants making an average of about $25,000 a year - "the front-line workforce," he said.

"They don't have access to any other type of housing," LeBlanc said.

"Their options are in an extended-stay motel that is twice as much or more, so they can't afford it. Or they can look at living in a car or on someone's sofa. That's it."

Shared space

Boarding or rooming houses played a key role in housing US urban workers for decades and, at the time, helped keep the homelessness rate close to zero, said Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

As recently as the 1960s, there may have been as many as 2 million such "single room occupancy" (SRO) units across the country, but today that number has probably fallen to fewer than 100,000, she said.

The alliance encourages cities to pay more attention to shared housing, Roman said, noting that getting the SRO number back to 2 million would "solve the homelessness crisis" for most individuals.

"We're 7 million units short of enough affordable housing, and we won't fill that anytime soon. So, people will have to share," she said.

LeBlanc at PadSplit began working on the idea in 2017 in recognition of the "wasted space" in many residential buildings.

"A formal dining room or home office - how often are those used?" he asked.

Some PadSplit units are in private homes - LeBlanc himself rents out a room in his house to tenants - while others are in multi-unit buildings.

PadSplit units are paid for on a weekly basis with utilities included, have no long-term commitment and give renters access to additional services like free telemedicine and credit reporting.

The company, which does background checks on all applicants, operates about 1,100 units, primarily in Atlanta, and is planning to move into multiple other cities, LeBlanc said.

Affordable solution?

City authorities are starting to look more closely at shared housing, though supporters say a host of zoning and other regulations remain obstacles in most jurisdictions, particularly rules on the number of unrelated people who can live together.

In 2019, lawmakers in San Jose, California, tweaked the zoning code to add co-living, allowing construction to begin on an 800-unit, 18-story project.

Offering private bedrooms and bathrooms, but shared kitchens and other living spaces, the project is reportedly the largest co-living building in the world.

And New York City is in the midst of a pilot project on shared housing that will see two companies, PadSplit and New York City-based Common, construct more than 300 units to serve primarily low-income residents.

"The construction of apartments with shared facilities can increase housing options for individuals who face a competitive market for small apartments," said Jeremy House, press secretary for the city's Housing Development Corporation.

Otherwise, those people "often end up living with roommates in larger apartments that could otherwise accommodate families," he said in emailed comments.

For instance, three single roommates can often afford to spend far more on rent than a family of four, which drives up the market rate of a three-bedroom apartment, explained Brad Hargreaves, chief executive officer at Common.

"If you can provide different solutions for single people who need housing, you're going to avoid them taking other units off the market," said Hargreaves, whose company launched five years ago and now operates in 10 cities.

While the concept of designed co-living remains new, he said, "I certainly think this will be part of affordable housing solutions going forward."

Newspaper headline: Closer quarters

A friend told her about a service called PadSplit, which connects tenants with shared housing options, similar to boarding houses and a growing trend in the US.

For $145 a week, including utilities - far less than an apartment would have cost her - Johnson found a room in a house with four other housemates, just minutes from her work, with a furnished bedroom, and shared bathroom, kitchen and living room.

Five months later, she was able to move out. "It gave me time to save enough money to get my own housing," Johnson, 30, told Reuters by phone.

Informal shared housing - when someone finds roommates and splits the cost of an apartment - remains a key way for young people to move to urban areas and join the workforce.

Formal shared housing - also known as co-living when it refers to tenants from higher income levels - differs in that a specialized firm vets applicants and typically deals with utility bills so tenants have just one monthly payment.

The rise of this type of housing has also allowed companies to construct or refurbish buildings specifically for this use.

The idea is not a new one but it is resurging in US cities as both residents and housing providers grapple with an ongoing shortage of affordable units.

Nearly half of realtors reported seeing an increase in "group-living" in 2019, according to the National Association of Realtors.

And that trend does not appear to have been slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the potential implications of an airborne virus for shared housing.

By the end of the second quarter of 2020, there were about 8,000 co-living "beds" in the US, with more than 54,000 more under development, according to a November report from real estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield.

Such options are up to 30 percent cheaper than studio apartments, the report found.

That does not surprise PadSplit founder Atticus LeBlanc, whose company focuses on tenants making an average of about $25,000 a year - "the front-line workforce," he said.

"They don't have access to any other type of housing," LeBlanc said.

"Their options are in an extended-stay motel that is twice as much or more, so they can't afford it. Or they can look at living in a car or on someone's sofa. That's it."

A contractor uses a roofing hammer while working on a home under construction in the Norton Commons subdivision in Louisville, Kentucky, the US, on March 23. Photo: VCG

Shared space

Boarding or rooming houses played a key role in housing US urban workers for decades and, at the time, helped keep the homelessness rate close to zero, said Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

As recently as the 1960s, there may have been as many as 2 million such "single room occupancy" (SRO) units across the country, but today that number has probably fallen to fewer than 100,000, she said.

The alliance encourages cities to pay more attention to shared housing, Roman said, noting that getting the SRO number back to 2 million would "solve the homelessness crisis" for most individuals.

"We're 7 million units short of enough affordable housing, and we won't fill that anytime soon. So, people will have to share," she said.

LeBlanc at PadSplit began working on the idea in 2017 in recognition of the "wasted space" in many residential buildings.

"A formal dining room or home office - how often are those used?" he asked.

Some PadSplit units are in private homes - LeBlanc himself rents out a room in his house to tenants - while others are in multi-unit buildings.

PadSplit units are paid for on a weekly basis with utilities included, have no long-term commitment and give renters access to additional services like free telemedicine and credit reporting.

The company, which does background checks on all applicants, operates about 1,100 units, primarily in Atlanta, and is planning to move into multiple other cities, LeBlanc said.

Affordable solution?

City authorities are starting to look more closely at shared housing, though supporters say a host of zoning and other regulations remain obstacles in most jurisdictions, particularly rules on the number of unrelated people who can live together.

In 2019, lawmakers in San Jose, California, tweaked the zoning code to add co-living, allowing construction to begin on an 800-unit, 18-story project.

Offering private bedrooms and bathrooms, but shared kitchens and other living spaces, the project is reportedly the largest co-living building in the world.

And New York City is in the midst of a pilot project on shared housing that will see two companies, PadSplit and New York City-based Common, construct more than 300 units to serve primarily low-income residents.

"The construction of apartments with shared facilities can increase housing options for individuals who face a competitive market for small apartments," said Jeremy House, press secretary for the city's Housing Development Corporation.

Otherwise, those people "often end up living with roommates in larger apartments that could otherwise accommodate families," he said in emailed comments.

For instance, three single roommates can often afford to spend far more on rent than a family of four, which drives up the market rate of a three-bedroom apartment, explained Brad Hargreaves, chief executive officer at Common.

"If you can provide different solutions for single people who need housing, you're going to avoid them taking other units off the market," said Hargreaves, whose company launched five years ago and now operates in 10 cities.

While the concept of designed co-living remains new, he said, "I certainly think this will be part of affordable housing solutions going forward."

Newspaper headline: Closer quarters

Posted in: AMERICAS