Railway ministry fails to grasp scope of chunyun chaos

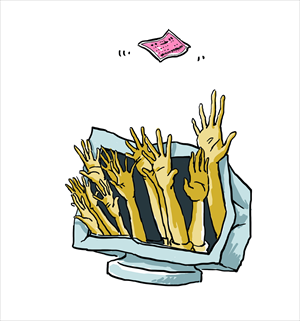

Illustration: Liu Rui

The really tough challenge for the Ministry of Railways (MOR) at the moment is not dealing with last year's train crash in Wenzhou. Liu Zhijun, the former head of the MOR who faces corruption charges, has to take responsibility for the tragedy, and the related people are punished, then the whole thing can be regarded as history.

The real problem is the Spring Festival travel period, known as chunyun. It comes every single year and never changes, like a recurring nightmare. We can blame the railway authorities, and it's not unreasonable to do so, but there's no ultimate solution to the chunyun chaos.

Over chunyun this year, 3.16 billion rail trips will be made, equivalent to everyone in the country travelling twice. This would be a grave problem in any country, but Chinese still manage to overcome their troubles and return home at last.

The two cancers of chunyun are the volume of passengers and the lack of transport. The first stems from a clash of popular custom and modern reality. Returning home was possible when people lived in nearby villages, but in an age of rapid urbanization, the distances to be covered are so much vaster. This can't be changed, but we should strive to fix the second problem, and ensure that people can travel home in decent conditions.

The scenes of buying tickets are shocking: in the roaring wind, anxious people queue day and night to get a ticket home. The lucky get crammed into a carriage like cattle, the unlucky pay ticket scalpers huge prices for the same privilege.

To make life easier for the public, the MOR reformed the ticket system by introducing a real-name registration system last year. An online and telephone purchasing system also started to operate this year. It attempted to not only expand purchasing channels but also attack the scalpers.

Unfortunately, the first group to suffer as a result of the new policy has been the migrant workers. They queue the hardest at chunyun, getting a ticket has become even tougher for them, like winning the lottery. As a result, they've written letters of complaint to the head of MOR, which have been reported by the media.

How did the policy go wrong? The people who created it spend all day sitting in comfortable offices. They have no concept of what it's like to labor all day at a construction site without having the time or resources to surf the Internet. Apparently, the policy has been more beneficial to the ticket scalpers, who can work in teams with explicit task division and have Internet skills. Was any research done on the implications of the policy? If so, who was it aimed at?

Theoretically, the MOR has managed chunyun for years and is quite familiar with the issues. But rather than come up with a solution, it just created a ticket-booking website that's constantly down and several phone lines which can almost never be reached.

I could understand the policy if it was an advert for an unknown website, but it's ridiculous to try and pass it off as a public service. Why weren't existing portal sites like Sina and Sohu used? Why not cooperate with 114, the services hotline? Modern government is supposed to be service-orientated. Nowadays, along with the shaping of civil society, the public is increasingly concerned with the administrative and state affairs, while the MOR is still acting blindly. Why does it rely solely on several officials and experts it trusts but neglect the vast voices from the public?

Inside the opaque administrative decision-making system, unexplained mysteries are actually hiding. Are the tickets that people are rushing to buy really the whole of those available, or are there still any spare ones? Can the ministry guarantee that nobody inside it is colluding with the ticket scalpers?

Considering the tragedy of the Wenzhou train crash, I cannot stop worrying. The public is ready to suffer the travails of chunyun, but they still hold a simple dream; everyone should suffer equally and fairly. Can the various so-called public servants really share the joys and sorrows alongside them?

The author is a media commentator based in Beijing. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

counterpoint: Flaws in new systems no reason to go backwards