Ghettos under fading red roofs

Look at the towering Gothic church and the endless red roofs on the two- and three-story houses from the right perspective, and you might think you were in 19th century Europe. But zoom out to take in the neighboring residential high-rises, and this vision collapses.

Qingdao, a coastal city in Shandong Province, is a former German colony long famed for its old town. But it's increasingly difficult to separate old from modern in the city, and many of the once-exotic colonial compounds have become ghettos packed with impoverished locals and migrant workers.

Many local residents and conservationists warn that the city's unique architecture is rapidly vanishing.

Harmonious blend

The old city of Qingdao was built during the German colonial period, after Germany was granted the concession by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) in 1897. After Germany's defeat in World War I, its former colonial territories in China were handed over to the Japanese, prompting mass protests by young Chinese. Qingdao became famous for its distinctive German brewery, using the old rendition of the city's name as Tsingtao.

Both the Germans and the Japanese built the basic infrastructure of the city today, as well as a large number of villas and public buildings. The Republic of China, led by the Kuomintang Party, retained the city framework and architectural flavor after taking it over in 1922, though it was then reoccupied by the Japanese invaders in 1938.

"Old Qingdao is a mixture of different styles, but they don't disturb each other, instead they coexist in harmony," said Jin Shan, a PhD student at the University of Stuttgart in Germany, majoring in architecture. The 30-year-old Qingdao local is an enthusiast for protecting his hometown's heritage.

However, the city's skyline was broken in the 1980s when newly built high-rises began dominating the view. To make way for the modern buildings, a large number of old structures have been dismantled, including many century-old liyuan (inner courtyards), Qingdao's signature buildings.

The liyuan were first built by the Germans to be used as shops, warehouses and residence for local Chinese. Only the colonizers and Chinese dignitaries could afford to live in villas and other luxury housing, and most local people grew up in the liyuan communities, for which they retain a particular affection.

"A city is not only about buildings. They carry people's memories and emotions," Jin said, estimating more than half of Qingdao's old buildings have disappeared.

Although Qingdao is not unique in boasting colonial buildings, as most other port cities that opened up early to foreigners also have century-old European architecture, Qingdao residents' attachment to their historical legacy is unparalleled. Local people take pride that the entire old town remained largely intact until the mass urbanization began three decades ago.

After decades of overuse and lack of maintenance, especially after 1949 when the private liyuan houses were confiscated by the government and crammed full of residents, these houses quickly dilapidated.

Due to a lack of sanitation facilities, the liyuan compounds can't meet modern day demands unless refurbished. People abandon the old city once they are able to afford housing in the newly developed eastern part of the city, leaving only the impoverished and migrant workers as tenants.

Like all other boomtowns in China, Qingdao focuses more on the future, not the past, as it expands its urban center and adds development zones, extending to both east and west as the century-old downtown is drained of its life.

Wandering around the former European section can disillusion visitors. Save for a few well-preserved houses, many buildings are worn or have even collapsed. Some liyuan courtyards have been turned into garbage dumps.

Ground view

The city authorities have tried to renovate the areas several times with different plans through the past decades. However, the biggest feature of the renovation projects is that old houses were dismantled and modern buildings were added, either high-rises or pseudo-archaic structures.

Today, the public buildings and luxury villas of the 1900s have generally been well-preserved and publicized as tourist attractions. But the large swathes of liyuan that once made up the majority of the old cityscape are disappearing to make way for new developments.

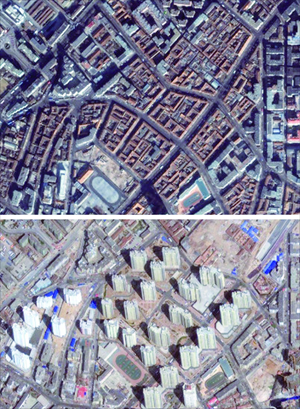

Jin recently posted a group of satellite pictures on his Weibo microblog that drew wide attention, revealing the staggering changes that took place in Qingdao's old city from 2003 to 2011. The pictures show that two large areas of old houses were flattened and new residential towers have been built over their "corpses," as Jin described it.

Residents don't need to resort to Google Earth to know the changes, though, as they happen under their own eyes.

The new developments are a sign that old houses are being wiped out in masses, rather than in the past when modern buildings appeared separately and usually take up only one courtyard each. As the lifeless new buildings have entrenched on the old city's heartland, "the worst has happened," Jin said. "After seeing that, I know the old city can never be restored," he added, despite once dreaming about subverting the trend of destruction and restoring the city's spirit.

"The more I saw the damage to the old town in recent years, the more I relished the original Qingdao," Jin said. He spent much of his childhood in the old town, and now relentlessly criticizes the urban planning authorities for what he describes as the mishandling of the city.

The experience of studying architecture in Germany for nine years has provided Jin with a rare insight on both the European and Chinese perspective. He is now working on his PhD dissertation focused on the construction of Qingdao during 1923-37.

The reconstruction to the old town is not without support. The majority of liyuan and other old houses have become tattered through the decades. The houses, which were originally built for a couple of families, are at present crammed with dozens of people, with extra rooms created with makeshift boarding.

Many of the residents in those houses were glad they were eventually relocated to the rebuilt high-rises with toilets and kitchens for every flat, leaving the surrounding residents that have yet to be relocated envious and expectant.

A resident on Ziyang Road who has lived in an old building for life, just opposite a newly excavated building, said he hopes to be relocated soon. The 47-year-old Qingdao local, surnamed Meng shares a home of less than 30 square meters with three other family members. In contrast, an elderly man who was relocated to the new residential tower was jubilant to relate how much his living condition has improved.

For conservationists and urban planning experts, however, this improvement of individual urban lives was achieved at too high a cost.

Keeping Qingdao spirit alive

Xu Feipeng, an architecture professor in Qingdao Technological University, shares Jin's views and calls the rapid destruction of the liyuan districts a failure. The neglect of the past parallels the situation of many other Chinese cities that "don't have much sense of preservation but are eager to show off a newfound modernity," said Xu. However, the two, both Qingdao natives, are divided over what is the best way to bring the old city back to life.

Xu is now heading a group of scholars and officials in a government-initiated renovation scheme for Zhongshan Road, the pivotal commercial street of the old Qingdao. He found that more than 80 percent of the house owners and previous residents in the area have moved to more prosperous and flashy new urban areas, leaving the old compounds gradually becoming ghettos packed with migrant workers and other out-of-towners.

"Based on this survey result, it's clear to see that the original social structure in this region has fragmented, so we can simply move these people out," Xu said. His answer to the eventual usage of these houses was that after preserving the old houses and rebuilding the teetering ones to their original appearance, the houses should be leased out and become shops.

However, Jin believes the best solution is to more effectively manage these communities including to step up sanitation and educate the residents.

"We must respect the natural selection that moved these people here and respect them. Through education and better property management the communities will gradually and eventually be face-lifted and reenergized," Jin said.

There is no specific planning for height control or regulations on new construction distance around the city-approved historic sites in Qingdao. However, In 2009, a century-old German fire-observation tower was dismantled, which prompted the Qingdao People's Congress to approve a protocol regulating the protection of cultural sites.

Zhang Dazhi, an official with the Qingdao Urban Planning Bureau, said the two newly finished high-rise residential communities were both approved before the new protocol took effect.

Zhang said such rebuilding projects are not likely to get approved any more. But for lovers of the city's heritage, the damage has already been done.