HOME >> CHINA

Judging a book by its cover

By Lin Meilian Source:Global Times Published: 2012-8-1 19:35:04

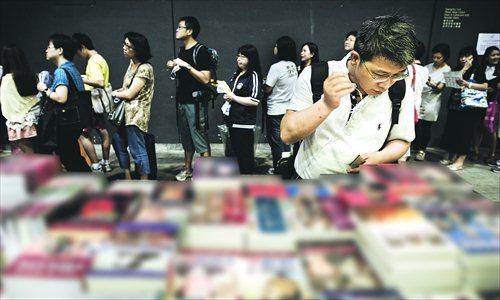

A man looks at Chinese political books at the Hong Kong Book Fair on July 18. More than 530 exhibitors from 20 countries took part in the six-day fair which drew in around 900,000 visitors. The annual event is known for shedding light on works that have been banned on the Chinese mainland. Photo: AFP

For many mainlanders, crossing the border from Hong Kong with a stack of potentially political contentious books in your bag can be a tense moment. Try and blend in. Follow the crowd. Pray that you won't be singled out to be searched by hawk-eyed customs officials.

Feng Chongyi, PhD, who carries a Chinese passport and is deputy director of the China Research Center at the University of Technology in Sydney, was not so lucky. Nine books that he brought into the mainland from Hong Kong were confiscated as being illegal printed materials back in June 2009.

He argued that they were legal publications from legitimate Hong Kong publishers and important to his research. However, the customs officials told him the books were on a list of banned works, which has not been released to the public.

Feng took the matter to the courts one month later but eventually lost the case.

Ever since individual tourists have been allowed to visit Hong Kong and Taiwan, mainland visitors have snapped up books on sensitive topics that are banned at home at the risk of being caught when crossing the border.

Ahead of the 18th CPC National Congress, books related to Chinese politics have become increasingly popular.

"They are curious to read the banned books for a true perspective on history and to find answers," Feng told the Global Times in an e-mail interview.

However, authorities do not see it this way. A high-level official was quoted as saying that such sources of information, including the banned books that are making their way into the mainland through diverse routes, made it hard for people to stay politically correct in today's complex society.

Mind what you read

The annual Hong Kong Book Fair that opened on July 18 was flooded with thousands of mainland visitors, seeking to browse banned works.

To attract more mainland visitors, the organizers even set up a special area, offering cheaper entrance tickets and putting controversial volumes front and center.

Authors such as Zhang Yihe, a female historian whose latest banned book is a collection of biographies of Peking Opera singers, were invited to give talks.

Huang Lilin, an 18-year-old high school student in Guangdong Province and a fan of Zhang, paid her first visit to Hong Kong to attend the book fair.

She told the Global Times that the trip had been eye-opening. She found Zhang's speech inspiring and was wracked with fear at going back through customs with two of her books in her bags.

"When I learned that Zhang's books were banned on the mainland, I was even more curious to read them," Huang said.

Experts divide the banned books into two main categories: serious ones about contemporary Chinese history and the ones churned out by shrewd publishers who take advantage of people's curiosity for "sensitive content" but a lot of them are proved to be fake.

Wong Kim-ching, manager of Cosmos Books in Hong Kong, told the Global Times that books such as biographies of Chinese leaders are their best-sellers, especially as the 18th CPC National Congress approaches.

This summer, books about Bo Xilai, the former Party chief of Chongqing Municipality who is suspected of being involved in serious discipline violations, were thriving in Hong Kong, he said.

Currently riding high on the best-seller list are Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, written by Ezra F. Vogel, and How Did the Red Sun Rise: The Cause and Effect of Zhengfeng in Yan'an, written by professor Gao Hua about the political nature of the Yan'an Rectification Movement (1942-45). Gao, a controversial historian from Nanjing University known for studying the Party's power struggles at the time, died at the age of 57 in December 2011.

"Some customers will buy a dozen of the same book and give them out as gifts," Wong said. "Mainlanders don't really listen to what we recommend. They seem to know what they are looking for."

Not to everyone's liking

However, not everyone is well-prepared to read books that present different perspectives. Joy Li, a university student from Beijing, told the Global Times that she was shocked after reading The Private Life of Chairman Mao: The Memoirs of Mao's Personal Physician at a friend's place. It took her quite a while to digest the information.

"I can't believe what I read. It showed me a total different image of Chairman Mao. I argued with my friends that it couldn't be true," she said.

She explains that young people like to read banned books to get a different perspective on China.

"We love our country and we want to know it better," she said. "The more information we can get, the clearer picture we can develop. We are adults. We selectively absorb the information. We can tell right from wrong."

Huang spent about 1,000 yuan on books including Zhang's The Memories Haven't Vanished, which tells of how prominent intellectuals suffered under the brutal attacks of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). She was lucky and got past customs safely, showing her victory by displaying the banned book on her Weibo account. Lawyer Tang Jingling, who took up Feng's court case, told the Global Times that with over 200,000 people crossing the border from Hong Kong to Shenzhen each day, it is impossible for customs officials to check all the luggage going through.

"But they have a blacklist," Tang said. "They will single out and check the luggage of the people whose names are on the blacklist." His claims could not be verified by the Global Times.

He added that anyone who gets caught of carrying "sensitive materials" will not face any charge or fine, but might be blacklisted.

Fuzzy wrong-doing

However, the blacklist of books has not been made public and neither is there a clear standard for what constitutes illicit printed material.

The term, illicitly printed material, has changed over the years. In the early 1980s, it referred to pornographic and superstitious materials. Later on, this definition was replaced by "materials harmful to China's politics, economy, culture and morality."

Li said that she was warned by a tour guide to ditch printed materials about the cult of Falun Gong before going through customs.

"When a Falun Gong protestor handed me the leaflet, I didn't pay attention and put it in my bag. Thank God the tour guide reminded me and saved me from getting into trouble," she said.

The Beijing Tourism Administration issued a notice to warn all travel agencies that beginning from this year, if a tourist is caught bringing "harmful materials" back into the mainland, the travel agency will be punished.

Some lawyers have suggested people who get caught simply hand over the books and leave, abandoning any plans to get the books back.

"It is not because these lawyers are afraid to lose the court case, it is because they don't want to offend officials," Tang said.

The only case that saw the customs lose was back in 2002 when a Beijing-based lawyer Zhu Yuantao was caught bringing in a copy of Gao Hua's aforementioned book. He sued the Beijing Airport Customs Office and then won on appeal in Beijing Higher People's Court.

However, two months later the court reversed its decision and upheld the seizure. Subsequent lawsuits over confiscated books have never been successful. Tang believes this is because authorities are afraid about setting a precedent.

The Beijing Airport Customs Office refused to comment for this case.

Holes in the wall

Readers do not necessarily need to go all the way to Hong Kong or Taiwan to buy banned books. Some are able to order them online or receive them through express delivery services that do not often censor the materials they transport.

E-books are also available for easy download and readers can buy pirate copies of books from private booksellers on the street.

However, this can have severe consequences. A bookseller in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province was arrested for copyright infringement and illegal management in 2009. He was sentenced to five years in jail for selling over 10,000 banned books on the mainland, the Yangtze Evening News reported.

The bookseller said he did not know those books were banned and just wanted to make money.

General Administration of Press and Publication spokesman Fan Weiping admitted that it is hard to bar politically harmful materials from entering the market.

"Those books that target our leaders, exaggerate the power struggle and spread rumors about the so-called hidden secrets of the Party have had an extremely negative influence on society," he told the Beijing News.

However, Feng calls for more acceptances and a positive attitude toward the banned materials. "There can be no limit to knowledge in a time of globalization; the authorities should revise their stance on this issue."

Zhu Yuanli contributed to this story

For many mainlanders, crossing the border from Hong Kong with a stack of potentially political contentious books in your bag can be a tense moment. Try and blend in. Follow the crowd. Pray that you won't be singled out to be searched by hawk-eyed customs officials.

Feng Chongyi, PhD, who carries a Chinese passport and is deputy director of the China Research Center at the University of Technology in Sydney, was not so lucky. Nine books that he brought into the mainland from Hong Kong were confiscated as being illegal printed materials back in June 2009.

He argued that they were legal publications from legitimate Hong Kong publishers and important to his research. However, the customs officials told him the books were on a list of banned works, which has not been released to the public.

Feng took the matter to the courts one month later but eventually lost the case.

Ever since individual tourists have been allowed to visit Hong Kong and Taiwan, mainland visitors have snapped up books on sensitive topics that are banned at home at the risk of being caught when crossing the border.

Ahead of the 18th CPC National Congress, books related to Chinese politics have become increasingly popular.

"They are curious to read the banned books for a true perspective on history and to find answers," Feng told the Global Times in an e-mail interview.

However, authorities do not see it this way. A high-level official was quoted as saying that such sources of information, including the banned books that are making their way into the mainland through diverse routes, made it hard for people to stay politically correct in today's complex society.

Mind what you read

The annual Hong Kong Book Fair that opened on July 18 was flooded with thousands of mainland visitors, seeking to browse banned works.

To attract more mainland visitors, the organizers even set up a special area, offering cheaper entrance tickets and putting controversial volumes front and center.

Authors such as Zhang Yihe, a female historian whose latest banned book is a collection of biographies of Peking Opera singers, were invited to give talks.

Huang Lilin, an 18-year-old high school student in Guangdong Province and a fan of Zhang, paid her first visit to Hong Kong to attend the book fair.

She told the Global Times that the trip had been eye-opening. She found Zhang's speech inspiring and was wracked with fear at going back through customs with two of her books in her bags.

"When I learned that Zhang's books were banned on the mainland, I was even more curious to read them," Huang said.

Experts divide the banned books into two main categories: serious ones about contemporary Chinese history and the ones churned out by shrewd publishers who take advantage of people's curiosity for "sensitive content" but a lot of them are proved to be fake.

Wong Kim-ching, manager of Cosmos Books in Hong Kong, told the Global Times that books such as biographies of Chinese leaders are their best-sellers, especially as the 18th CPC National Congress approaches.

This summer, books about Bo Xilai, the former Party chief of Chongqing Municipality who is suspected of being involved in serious discipline violations, were thriving in Hong Kong, he said.

Currently riding high on the best-seller list are Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, written by Ezra F. Vogel, and How Did the Red Sun Rise: The Cause and Effect of Zhengfeng in Yan'an, written by professor Gao Hua about the political nature of the Yan'an Rectification Movement (1942-45). Gao, a controversial historian from Nanjing University known for studying the Party's power struggles at the time, died at the age of 57 in December 2011.

"Some customers will buy a dozen of the same book and give them out as gifts," Wong said. "Mainlanders don't really listen to what we recommend. They seem to know what they are looking for."

Not to everyone's liking

However, not everyone is well-prepared to read books that present different perspectives. Joy Li, a university student from Beijing, told the Global Times that she was shocked after reading The Private Life of Chairman Mao: The Memoirs of Mao's Personal Physician at a friend's place. It took her quite a while to digest the information.

"I can't believe what I read. It showed me a total different image of Chairman Mao. I argued with my friends that it couldn't be true," she said.

She explains that young people like to read banned books to get a different perspective on China.

"We love our country and we want to know it better," she said. "The more information we can get, the clearer picture we can develop. We are adults. We selectively absorb the information. We can tell right from wrong."

Huang spent about 1,000 yuan on books including Zhang's The Memories Haven't Vanished, which tells of how prominent intellectuals suffered under the brutal attacks of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). She was lucky and got past customs safely, showing her victory by displaying the banned book on her Weibo account. Lawyer Tang Jingling, who took up Feng's court case, told the Global Times that with over 200,000 people crossing the border from Hong Kong to Shenzhen each day, it is impossible for customs officials to check all the luggage going through.

"But they have a blacklist," Tang said. "They will single out and check the luggage of the people whose names are on the blacklist." His claims could not be verified by the Global Times.

He added that anyone who gets caught of carrying "sensitive materials" will not face any charge or fine, but might be blacklisted.

Fuzzy wrong-doing

However, the blacklist of books has not been made public and neither is there a clear standard for what constitutes illicit printed material.

The term, illicitly printed material, has changed over the years. In the early 1980s, it referred to pornographic and superstitious materials. Later on, this definition was replaced by "materials harmful to China's politics, economy, culture and morality."

Li said that she was warned by a tour guide to ditch printed materials about the cult of Falun Gong before going through customs.

"When a Falun Gong protestor handed me the leaflet, I didn't pay attention and put it in my bag. Thank God the tour guide reminded me and saved me from getting into trouble," she said.

The Beijing Tourism Administration issued a notice to warn all travel agencies that beginning from this year, if a tourist is caught bringing "harmful materials" back into the mainland, the travel agency will be punished.

Some lawyers have suggested people who get caught simply hand over the books and leave, abandoning any plans to get the books back.

"It is not because these lawyers are afraid to lose the court case, it is because they don't want to offend officials," Tang said.

The only case that saw the customs lose was back in 2002 when a Beijing-based lawyer Zhu Yuantao was caught bringing in a copy of Gao Hua's aforementioned book. He sued the Beijing Airport Customs Office and then won on appeal in Beijing Higher People's Court.

However, two months later the court reversed its decision and upheld the seizure. Subsequent lawsuits over confiscated books have never been successful. Tang believes this is because authorities are afraid about setting a precedent.

The Beijing Airport Customs Office refused to comment for this case.

Holes in the wall

Readers do not necessarily need to go all the way to Hong Kong or Taiwan to buy banned books. Some are able to order them online or receive them through express delivery services that do not often censor the materials they transport.

E-books are also available for easy download and readers can buy pirate copies of books from private booksellers on the street.

However, this can have severe consequences. A bookseller in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province was arrested for copyright infringement and illegal management in 2009. He was sentenced to five years in jail for selling over 10,000 banned books on the mainland, the Yangtze Evening News reported.

The bookseller said he did not know those books were banned and just wanted to make money.

General Administration of Press and Publication spokesman Fan Weiping admitted that it is hard to bar politically harmful materials from entering the market.

"Those books that target our leaders, exaggerate the power struggle and spread rumors about the so-called hidden secrets of the Party have had an extremely negative influence on society," he told the Beijing News.

However, Feng calls for more acceptances and a positive attitude toward the banned materials. "There can be no limit to knowledge in a time of globalization; the authorities should revise their stance on this issue."

Zhu Yuanli contributed to this story

Posted in: In-Depth