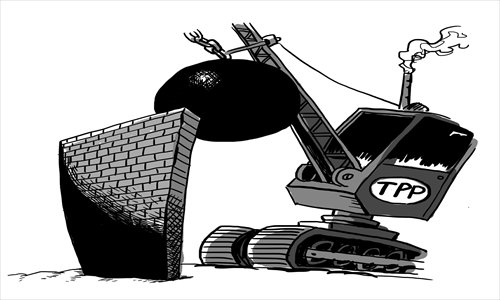

Messy TPP process no reason for China to fear

View Point: New agreements by US do not block Asian integration

The US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) has become a topic of major controversy in Japan and China over the last two years. Chinese commentators have warned that it is a policy of economic encirclement by the US and allies, while the Japanese public has fretted that joining the TPP will amount to an Americanization of their economy.

In the US, however, there is virtually no public debate at all over the TPP, and only specialists in trade and Asian international relations know what the letters stand for.

While late 20th century trade negotiations began to see a major expansion of issues seen as trade-related, including internal intellectual property rights and various industrial policy measures, the TPP is meant to go deeper. In theory, the TPP will create a fully level playing field for goods, services, and investment among countries and make regional production networks nearly frictionless.

A proper understanding of the TPP requires an understanding of US trade politics. The US public is increasingly skeptical of the benefits of free trade. They have seen significant outsourcing and deindustrialization without recognizing that they benefit from lower prices or that, in the aggregate, low value-added jobs are being replaced by better ones.

Instead, they tend to blame economic stagnation and growing inequality on globalization rather than on technological change, regressive tax policies, and insufficient investment in education and infrastructure.

It has thus become extraordinarily politically difficult to ratify any trade agreements at all. The last three FTAs approved by the US Congress took over three years to be ratified even with fast-track arrangements in place. Meanwhile, the Doha Development Round appears to be dead.

It was in the context of this poisonous political atmosphere that free-trade advocates latched onto the TPP as a means of advancing their agenda. The TPP had a long time horizon and uncontroversial partners such as Australia and Singapore.

But the assumption that TPP partners would start out small and uncontroversial has been immeasurably complicated by Japan's public discussion about joining.

From the first, TPP advocates in the US were deeply split over the inclusion of Japan. On the one hand, they recognized the enormous gains to be made from further opening the world's third-largest economy. On the other hand, they feared the Japanese political system would delay negotiations, and that suspicion of Japan in the US Congress would make US approval of any agreement far less likely.

In Japan, the politics were even more complicated. Japanese farmers, garment makers, and other protected groups have long been deeply opposed to trade agreements of all kinds.

Although Japan has concluded a surprising number of FTAs, all involved carve-outs for politically significant producers. Reformers in Japan have been fighting to open up markets for years with only partial success. They see TPP as a last-ditch opportunity for a comprehensive approach to liberalizing the Japanese economy.

It has been very difficult to ensure political support, which is why Japan is still dithering over a year and a half after it first approached Washington about joining. With Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda deeply weakened by the recent fight over a consumption tax increase, discussion of a formal request to join the TPP has been postponed until after the next election.

Much of the TPP story in the US and Japan should be understood as the messy democratic process at work. It is understandable that Chinese may see the TPP as a strategy of encirclement. The need for governments in both the US and Japan to please skeptical publics means that the prospects for the successful conclusion of the TPP are remote.

China would do better to focus on trade facilitation and improving its own existing FTAs, rather than on fretting over the threat of encirclement through the TPP.

The author is chair of the Department of International Relations and Professor of International Relations and Political Science at Boston University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn