China-bashing doesn't match US values

In US presidential debates, Republican candidate Mitt Romney claims that he would label China as a currency manipulator on "Day One" in the White House. It is a sharp contrast to the president's "No Drama Obama" approach to China policy.

In the cacophony of China-bashing and scapegoat rhetoric, Beijing's currency manipulation is a major concern for the Republican Party.

The issue, however, is a double-edged sword: US insistence on the appreciation of the yuan might benefit the national manufacturing sector, but will surely lead to higher costs for US consumers for imported Chinese goods.

The real question is the national debt, for which China and Japan hold $1.15 trillion and $1.12 trillion respectively.

When the Chinese share of our national debt as a percentage of the total US public debt, and the yearly interest payment of over $25 billion to China, declined over the past two years, the value of the yuan exchange rate against the dollar appreciated. And US trade deficit with China declined.

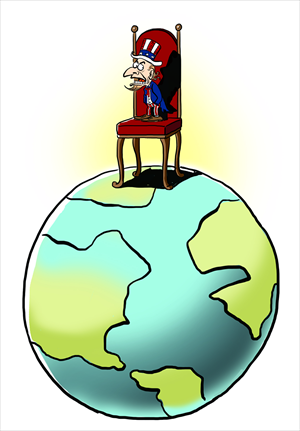

The larger question is: Should the Republicans battle with the US's leading banker, world's largest low-cost exporter, and the US's growing export market?

Unlike Romney's changing campaign tactics and policy positions, the Obama administration quietly and persistently imposed tariffs on Chinese tires and filed subsidy complaints against Beijing at the WTO.

In the meantime, the Sino-US Strategic and Economic Dialogue is deepening as the White House unveiled the Asia pivot strategy along with the Trans-Pacific Partnership to expand US exports.

US foreign policy is often divided into Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian, referring to the US's founding rivals Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, and their differing vision.

The purpose-driven Obama's strategic policy architecture is Hamiltonian, focused around a realistic assessment and use of US strengths, with a new trade and military strategy in the Indo-Pacific region.

More idealistic Jeffersonian aspirations of religious freedom and human rights have been placed in the pragmatic framework of the president's larger strategic vision.

With the US's retreat from the Indian and Pacific ocean regions in recent years, China has attempted to restore its international legitimacy and historical supremacy.

As the crown jewel of the multibillion-dollar Chinese "String of Pearls" naval strategy across the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea, Beijing is now constructing the over $100 million Lotus Tower in Colombo, the largest city of Sri Lanka.

The soaring telecommunication tower symbolizes not only Beijing's foreign policy slogans of "Peaceful Rise" and "Harmonious Society," but also projects a symbol of ancient power radiating from the Middle Kingdom.

Suddenly awakened to this reality, Obama's Asian pivot strategy is intended to realize the US's founding vision of Jefferson's "Empire of Liberty" in the Indo-Pacific region.

Shortsighted China-bashing with political rhetoric, trade tactics, and military battles is counterproductive, and it would most likely be costlier than the two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

The vibrant and more educated young Chinese, who are already exposed to the taste of liberty and social networks, would be the 21st century's missiles of freedom. These include trade delegations, academic exchanges, cultural connections, scientific contacts, and the use of other "soft-power" instruments - from both sides of the Pacific.

Like the US's progress toward the eventual Jeffersonian ideals of equality, the next Chinese "fairness revolution" will organically rise from internal sources.

China doesn't need to worry about US containment. The two intertwined Chinese and US economies must succeed for mutual prosperity and social stability by creating more wealth and jobs.

Beijing has now begun to unfold the balancing act of reviving China's historical role balanced between might, with its ancient maritime claims and imperial ambitions with legitimacy, and right, with its Confucian virtues and Asian values.

With these complexities, the US needs a better understanding of China's history and struggles when formulating policies that can realize the founding vision of the US, tempered with realism.

The author is a senior fellow and affiliate professor of public and international affairs at George Mason University's School of Public Policy. He is also a visiting professor in the Center for American Studies at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, a former military professor and diplomat during the Clinton and Bush administrations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn