HOME >> ARTS

Conveying a culture

By Lu Qianwen Source:Global Times Published: 2012-11-6 19:55:07

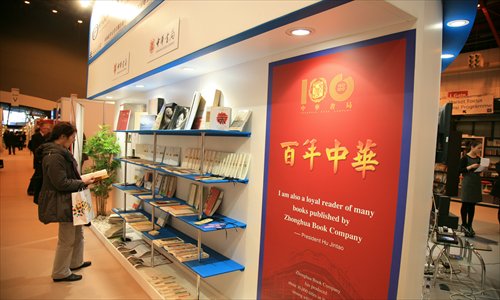

Chinese literature at 2012 London Book Fair Photo: CFP

For a Chinese writer planning to publish his book overseas, finding a capable and qualified translator is of the utmost importance. For years, not only authors, but government and academic institutions have been trying to scout or nurture a stable of competent translators to ensure the quality of the original works.

"Technically, works of modern Chinese literature have been going out [to foreign countries] since the early 20th century, including writers like Lu Xun," said Liu Jiangkai, a researcher at the Research Center of Chinese Literature Overseas Dissemination at Beijing Normal University.

According to Liu, before the 1980s it was usually official organizations like the Foreign Language Press that undertook the task of translating works by domestic writers. "But since 1990s, writers began to seek translators by themselves, … among which the works of Mo Yan, Su Tong and Yu Hua were the first group to be introduced abroad," Liu told the Global Times.

Literary deficit

"The works introduced in and out each year are extremely imbalanced, with no more than 10 domestic works translated per year," said Liu.

According to the research by Goran Malmqvist, a permanent member of the judge panel of the Nobel Literature Prize, from 2005 to 2007, among all the works translated into Swedish, English works took up 74 percent; French works were 3.6 percent and German was about 2 percent. But the overall from Asian works amounted to less than 1 percent of the total.

"This is not just in Sweden, but almost all of Europe," Malmqvist said.

But now, state and local governments as well as some private publishers are all financing their own translations of domestic writers' works. In 2010, Chinese Literature Today, the first English magazine about Chinese literature was initiated by Beijing Normal University and the University of Oklahoma in the US. They will soon publish their 5th issue.

Last year, Pathlight, the English version of flagship Chinese literature magazine People's Literature, was launched, and the upcoming issue will be its 3rd.

However, due to the lack of resources like professional translators and book agents, the efforts of government and private organizations are taking effect slowly.

"Foreign publishers are prone to publish those works translated by their native speakers," said Wang Mengda, a Swedish teacher from Shanghai International Studies University, "and it's impossible for Chinese colleges to invest so much to cultivate a professional translator of small languages."

Translation makes the difference

Thanks to the Nobel Literature Prize this year, Mo Yan and his works have been placed in the spotlight. "He has a strong legion of translators in different countries," said Liu, "His English translator Howard Goldblatt, Japanese translator Fujii Shozo, French translator Chantal Chen-Andro, all are great translators and masters in literature."

"A great translator makes a big difference," Liu said. "Take Howard Goldblatt for example; he has translated books like Wolf Totem by Jiang Rong and Turbulence by Jia Pingwa. Both these books became more popular overseas after Goldblatt's translation," he noted.

In fact, writers like Jia Pingwa, Chen Zhongshi and Wang Anyi possess as much literary significance as Mo Yan for domestic readers. But their overseas reputation was limited by inadequate or uninspired translation of their works.

"Though Shaanxi writers such as Jia and Chen enjoy an advantage domestically, their works are hard to be translated and understood by foreign readers since they involve many local dialects and customs," said Lei Tao, executive vice president of Shaanxi Writers Association.

"Since 2008 we have initiated the SLOT (Shaanxi Literature Overseas Translation) project, which aims at translating local writers' works," Lei told the Global Times. "But the work has been slow and the quality of the translation is not guaranteed," he said.

Translation obstacles

"Currently the translation of Chinese works are mainly completed by sinologists... who understand Chinese language and culture," said Liu. But the sad truth is that the total number of sinologists across the West amounts to no more than 20 individuals, which leads to not just a shortage of Chinese literature works in the region, but also to a substandard quality of translation because many are translations of other translations.

Meanwhile, the writing of Chinese cultural traditions featured in some works adds much to the difficulty. American translator Michael Berry translated To Live by Yu Hua in 2004.

"I know some names in his book like Fugui and Chunsheng have their specific meanings, but it was hard to translate in English. I hesitated about whether to directly use pinyin or paraphrase them, but finally in most cases I chose to use pinyin," Berry told The Beijing News.

However, despite various translation problems, a good thing is that Chinese writers are beginning to place more emphasis on the quality of the translation.

Li Er, author of long novels Truth and Variations and Cherry on Pomegranate Tree, which have both been published in German, refused his overseas' publishers suggestion to publish a Spanish version of his books, even though translating directly from German to Spanish will greatly reduce the time.

Many insiders believe only native speakers of foreign languages can translate the works in accordance with foreign readers' reading habit. But in Liu's view, the industry should also cultivate domestic language learners to become qualified translators.

"A capable translator needs to be equipped with three qualities," he pointed out. "First, the translator should be a writer himself…; second, he also should be an academic researcher and know about Chinese and foreign literature; and third, he must be a master of languages."

To make it happen, Liu said, "The government can finance more domestic scholars and students to attend foreign institutes each year, enabling them to be immersed into a real different language and cultural environment."

For a Chinese writer planning to publish his book overseas, finding a capable and qualified translator is of the utmost importance. For years, not only authors, but government and academic institutions have been trying to scout or nurture a stable of competent translators to ensure the quality of the original works.

"Technically, works of modern Chinese literature have been going out [to foreign countries] since the early 20th century, including writers like Lu Xun," said Liu Jiangkai, a researcher at the Research Center of Chinese Literature Overseas Dissemination at Beijing Normal University.

According to Liu, before the 1980s it was usually official organizations like the Foreign Language Press that undertook the task of translating works by domestic writers. "But since 1990s, writers began to seek translators by themselves, … among which the works of Mo Yan, Su Tong and Yu Hua were the first group to be introduced abroad," Liu told the Global Times.

Literary deficit

"The works introduced in and out each year are extremely imbalanced, with no more than 10 domestic works translated per year," said Liu.

According to the research by Goran Malmqvist, a permanent member of the judge panel of the Nobel Literature Prize, from 2005 to 2007, among all the works translated into Swedish, English works took up 74 percent; French works were 3.6 percent and German was about 2 percent. But the overall from Asian works amounted to less than 1 percent of the total.

"This is not just in Sweden, but almost all of Europe," Malmqvist said.

But now, state and local governments as well as some private publishers are all financing their own translations of domestic writers' works. In 2010, Chinese Literature Today, the first English magazine about Chinese literature was initiated by Beijing Normal University and the University of Oklahoma in the US. They will soon publish their 5th issue.

Last year, Pathlight, the English version of flagship Chinese literature magazine People's Literature, was launched, and the upcoming issue will be its 3rd.

However, due to the lack of resources like professional translators and book agents, the efforts of government and private organizations are taking effect slowly.

"Foreign publishers are prone to publish those works translated by their native speakers," said Wang Mengda, a Swedish teacher from Shanghai International Studies University, "and it's impossible for Chinese colleges to invest so much to cultivate a professional translator of small languages."

Translation makes the difference

Thanks to the Nobel Literature Prize this year, Mo Yan and his works have been placed in the spotlight. "He has a strong legion of translators in different countries," said Liu, "His English translator Howard Goldblatt, Japanese translator Fujii Shozo, French translator Chantal Chen-Andro, all are great translators and masters in literature."

"A great translator makes a big difference," Liu said. "Take Howard Goldblatt for example; he has translated books like Wolf Totem by Jiang Rong and Turbulence by Jia Pingwa. Both these books became more popular overseas after Goldblatt's translation," he noted.

In fact, writers like Jia Pingwa, Chen Zhongshi and Wang Anyi possess as much literary significance as Mo Yan for domestic readers. But their overseas reputation was limited by inadequate or uninspired translation of their works.

"Though Shaanxi writers such as Jia and Chen enjoy an advantage domestically, their works are hard to be translated and understood by foreign readers since they involve many local dialects and customs," said Lei Tao, executive vice president of Shaanxi Writers Association.

"Since 2008 we have initiated the SLOT (Shaanxi Literature Overseas Translation) project, which aims at translating local writers' works," Lei told the Global Times. "But the work has been slow and the quality of the translation is not guaranteed," he said.

Translation obstacles

"Currently the translation of Chinese works are mainly completed by sinologists... who understand Chinese language and culture," said Liu. But the sad truth is that the total number of sinologists across the West amounts to no more than 20 individuals, which leads to not just a shortage of Chinese literature works in the region, but also to a substandard quality of translation because many are translations of other translations.

Meanwhile, the writing of Chinese cultural traditions featured in some works adds much to the difficulty. American translator Michael Berry translated To Live by Yu Hua in 2004.

"I know some names in his book like Fugui and Chunsheng have their specific meanings, but it was hard to translate in English. I hesitated about whether to directly use pinyin or paraphrase them, but finally in most cases I chose to use pinyin," Berry told The Beijing News.

However, despite various translation problems, a good thing is that Chinese writers are beginning to place more emphasis on the quality of the translation.

Li Er, author of long novels Truth and Variations and Cherry on Pomegranate Tree, which have both been published in German, refused his overseas' publishers suggestion to publish a Spanish version of his books, even though translating directly from German to Spanish will greatly reduce the time.

Many insiders believe only native speakers of foreign languages can translate the works in accordance with foreign readers' reading habit. But in Liu's view, the industry should also cultivate domestic language learners to become qualified translators.

"A capable translator needs to be equipped with three qualities," he pointed out. "First, the translator should be a writer himself…; second, he also should be an academic researcher and know about Chinese and foreign literature; and third, he must be a master of languages."

To make it happen, Liu said, "The government can finance more domestic scholars and students to attend foreign institutes each year, enabling them to be immersed into a real different language and cultural environment."

Posted in: Books