HOME >> CHINA

Sci-fi made in China

By Xuyang Jingjing Source:Global Times Published: 2013-1-7 18:53:01

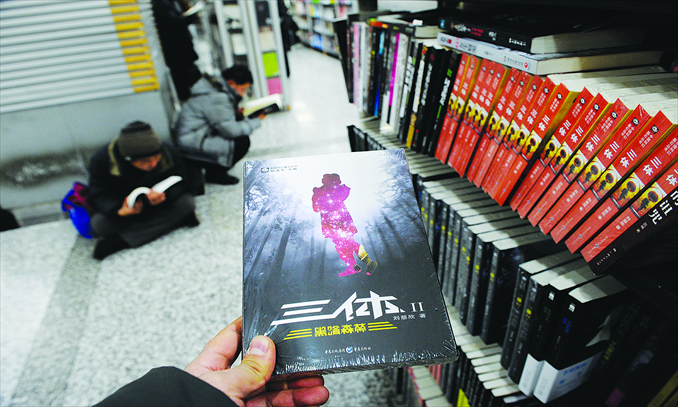

A copy of the popular science fiction novel Three Body in the Beijing Books Building Photo: Li Hao/GT

This is the time of year when people wrap up the last 12 months and look to the future, when pundits and strategists predict what China or the world will become over the next year or the next decade. But a brave few souls go much further and depict all types of future imaginable for humanity, if not the entire universe.

Science fiction, despite remaining a marginal genre here, is slowly making a comeback in China. Long considered a branch of children's literature, science fiction today has been maturing. The rise of China and the problems caused by its rapid development provide ample materials for science fiction writers to feed their imaginations.

Science fiction as a genre is closely related to the progress of science and technology. Many scholars have pointed out that it's no coincidence that the first science fiction novel was published in industrial-era Britain.

Brainchild to bestseller

Scholars and sci-fi writers point out that China has seen three booms of sci-fi texts. At the turn of the last century translations of writers such as Jules Verne had a major influence on late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) writers. However, this movement did not survive the ensuing wars and revolutions.

The late 1970s and early 1980s, the early years of reform and opening-up, saw another boom in sci-fi stories, though some of them were written much earlier than their publication dates would suggest.

Ye Yonglie, one of the earliest sci-fi writers in China, wrote a novel in 1961, which presented a technology-enabled future of convenience. But his story wasn't published until 1978, after the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

Stories like Ye's are representative of the imagination and mind-set of an era where the country was very much focused on modernization through science and technology. Most science fiction stories then talked about the bright future science would bring. There was also an obvious influence from the Soviet Union.

But this nascent sci-fi scene didn't last long. In 1983, the government launched a campaign to eradicate the "pollution" of Western thoughts and lifestyles that were flourishing as the country opened its doors to the world. Science fiction was targeted as being unrealistic, fantastical and useless.

After going through the wilderness, it wasn't until the last decade that science fiction underwent a third wind. Liu Cixin is one of the best known sci-fi writers in China. His acclaimed Three Body trilogy has sold at least 400,000 copies and is about to be translated into English.

Set against the backdrop of China's Cultural Revolution, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans its invasion of Earth, while on Earth, people form into different camps to either welcome the superior beings to take over a world seen as corrupt, or to fight against the invasion.

Heavily influenced by science fiction legend Arthur C. Clarke, Liu's novels place more on technical and scientific explanations than on characters or plot. The basis of Three Body, which took him over five years to finish, is the "three-body problem" where a system with three interacting objects is highly unpredictable. Its technical depictions can make the books seem cold and detached, but they still depict a grand imagination and draw readers into a different world.

A computer engineer by day, Liu, 49, started out as a sci-fi fan and began writing part time in his early 20s. He published his first short story in 1999. He said he is more conscious of the common themes of the genre, which treat humanity as a whole and dwell upon ultimate questions such as the future of civilization or life itself.

Liu admits that there aren't as many heavy sci-fi works as in the genre's post-war golden age. "Perhaps the rapid development of science has made it less magical as in the past, and there is now more emphasis on the negative impact of science," said Liu.

What Liu loves most about science fiction is creating a whole new world. "It's also a way of thinking and looking at things," said Liu. "It shows you all the different possibilities of the future."

Universe of themes

While dealing with common themes such as science being a double-edged sword or a clash of civilizations somewhere in space, contemporary Chinese science fiction has nonetheless shown a distinct Chinese flavor and its own concerns and perspectives.

"We see in traditional science fiction that Western countries save the world in the face of a major crisis, but in Chinese sci-fi literature, we see the role China plays," said Yao Haijun, deputy editor in chief of Science Fiction World, a popular sci-fi magazine running for over 30 years.

Yao said the subject matter has to do with the rise of China but it has also caught the eye of Western readers and researchers who want to look into China's future through such stories.

In Han Song's 2066: Red Star Over America, first published in 2000, the US has declined and China has become the dominant power in the world. Players of traditional Chinese game, go, are sent to spread their superior civilization to America. During their stay in the US, they see terrorists take down the Twin Towers and plunge the country into chaos. But such predictions do not necessarily show confidence or arrogance about China's power. Writers have shown deep concern about the rapid development of China and the problems it could cause today or in the future.

In this context many science fiction stories are in fact a response to or a reflection of reality but with more imagination, said Song Mingwei, assistant professor of Chinese at Wellesley College, Massachusetts. Song said that the reality of China provides an experimental field for both utopian and dystopian sci-fi.

One example is Life of Ants, by Wang Jinkang. Set during the Cultural Revolution, the main character Yan Zhe is an intellectual youth sent to work in the countryside. Disappointed with the dark side of humanity, he decides to use ant hormones to make people altruistic, disciplined and hardworking. Yan creates a society in which he rules over his hardworking "ants" but his utopia eventually crumbles.

"My main point in writing this novel is that I don't want an almighty god to control the world because there's no way to guarantee his goodness, since eventually he would be corrupted by power," said Wang, 64. Song commented that Yan's utopian experiment essentially epitomizes the experiment of China at the time.

Holding up a mirror

While Wang delves into the past for inspirations, Han Song is very much looking ahead. Han says his job as a journalist at Xinhua News Agency gives him access to the real China.

Many writers and scholars have said that living in today's China sometimes feels surreal. In an earlier interview with the Global Times, Han said that sometimes writing news feels like science fiction.

It seems that Han is fascinated with the rapid development of China, especially transportation. In Subway, published in 2010, Han wrote about a subway train that mysteriously disappears at night and enters a seemingly endless tunnel. Passengers on the speeding train eat and mate with each other, eventually evolving into new lifeforms. It turns out that the train is part of a government subway project which is attempting to connect to the broader universe.

In 2012 he published a book entitled High-speed Railway, which begins with a high-speed railway accident. Shortly after Han finished the book, on July 23, two bullet trains collided in Wenzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province, killing at least 40 people and injuring over 200.

In the prefaces and epilogues to the two books, Han wrote about the country's huge investment in building railways and independently developing high-speed railway technologies. Since the first subway line opened in 1969, China has been playing catchup with the Western world and long seen total railway mileage as a symbol of the nation's power and revival.

Yet the rapid development that is often referred to as a miracle has left many people feeling surreal and concerned, much like Han. Reality is what inspires him. Strange, dark, and sometimes horrific, Han's novels are filled with violence, confusion and chaos. His style is often described as kafkaesque.

"There is one aspect of China that has not been written enough, and that's this kafkaesque absurdity of reality," Han told Southern Metropolis Weekly.

Writers admit that the atmosphere for fictional novels has become more tolerant. Most of their works eventually get published, although publishers are still cautious about references to the Cultural Revolution and the darkness of certain stories. Many of them have to go through several publishing houses before finding their luck.

"I think we are now at a good time for science fiction," said Yao. "We have cultivated a group of strong writers, a steady and growing fan base and we are hopeful." Circulation of his Science Fiction World magazine has grown from several thousand to 400,000 copies at its peak.

Still compared to the US where thousands of science fiction titles are published each year, only a hundred or so are published in China. Good writers are also in short supply. "For a long time people didn't believe there's a market for science fiction in China, but I think recent years have proved that is wrong," said Yao.

Unlike in some Western countries where the scientific community embraces science fiction and is involved in writing sci-fi novels, there is little overlap in China. For a long time the country viewed science and technology only as tools, with scientists not supposed to do anything other than research. Only very recently have certain scientists started to venture into sci-fi writing.

There have been other promising changes of late. In particular, as Three Body gained popularity, many publishers have shown their interest in publishing science fiction works.

However, Yao said he is worried that when seeing the market potential of sci-fi literature, some publishers might become short-sighted and too focused on profits rather than fostering good writers and stories, which remain the most important thing.

Sticking to his classic science fiction tradition, Liu is concerned that future writers and readers will see the future moving so fast that science fiction might lose its magic and appeal.

This is the time of year when people wrap up the last 12 months and look to the future, when pundits and strategists predict what China or the world will become over the next year or the next decade. But a brave few souls go much further and depict all types of future imaginable for humanity, if not the entire universe.

Science fiction, despite remaining a marginal genre here, is slowly making a comeback in China. Long considered a branch of children's literature, science fiction today has been maturing. The rise of China and the problems caused by its rapid development provide ample materials for science fiction writers to feed their imaginations.

Science fiction as a genre is closely related to the progress of science and technology. Many scholars have pointed out that it's no coincidence that the first science fiction novel was published in industrial-era Britain.

Brainchild to bestseller

Scholars and sci-fi writers point out that China has seen three booms of sci-fi texts. At the turn of the last century translations of writers such as Jules Verne had a major influence on late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) writers. However, this movement did not survive the ensuing wars and revolutions.

The late 1970s and early 1980s, the early years of reform and opening-up, saw another boom in sci-fi stories, though some of them were written much earlier than their publication dates would suggest.

Ye Yonglie, one of the earliest sci-fi writers in China, wrote a novel in 1961, which presented a technology-enabled future of convenience. But his story wasn't published until 1978, after the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

Stories like Ye's are representative of the imagination and mind-set of an era where the country was very much focused on modernization through science and technology. Most science fiction stories then talked about the bright future science would bring. There was also an obvious influence from the Soviet Union.

But this nascent sci-fi scene didn't last long. In 1983, the government launched a campaign to eradicate the "pollution" of Western thoughts and lifestyles that were flourishing as the country opened its doors to the world. Science fiction was targeted as being unrealistic, fantastical and useless.

After going through the wilderness, it wasn't until the last decade that science fiction underwent a third wind. Liu Cixin is one of the best known sci-fi writers in China. His acclaimed Three Body trilogy has sold at least 400,000 copies and is about to be translated into English.

Set against the backdrop of China's Cultural Revolution, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans its invasion of Earth, while on Earth, people form into different camps to either welcome the superior beings to take over a world seen as corrupt, or to fight against the invasion.

Heavily influenced by science fiction legend Arthur C. Clarke, Liu's novels place more on technical and scientific explanations than on characters or plot. The basis of Three Body, which took him over five years to finish, is the "three-body problem" where a system with three interacting objects is highly unpredictable. Its technical depictions can make the books seem cold and detached, but they still depict a grand imagination and draw readers into a different world.

A computer engineer by day, Liu, 49, started out as a sci-fi fan and began writing part time in his early 20s. He published his first short story in 1999. He said he is more conscious of the common themes of the genre, which treat humanity as a whole and dwell upon ultimate questions such as the future of civilization or life itself.

Liu admits that there aren't as many heavy sci-fi works as in the genre's post-war golden age. "Perhaps the rapid development of science has made it less magical as in the past, and there is now more emphasis on the negative impact of science," said Liu.

What Liu loves most about science fiction is creating a whole new world. "It's also a way of thinking and looking at things," said Liu. "It shows you all the different possibilities of the future."

Universe of themes

While dealing with common themes such as science being a double-edged sword or a clash of civilizations somewhere in space, contemporary Chinese science fiction has nonetheless shown a distinct Chinese flavor and its own concerns and perspectives.

"We see in traditional science fiction that Western countries save the world in the face of a major crisis, but in Chinese sci-fi literature, we see the role China plays," said Yao Haijun, deputy editor in chief of Science Fiction World, a popular sci-fi magazine running for over 30 years.

Yao said the subject matter has to do with the rise of China but it has also caught the eye of Western readers and researchers who want to look into China's future through such stories.

In Han Song's 2066: Red Star Over America, first published in 2000, the US has declined and China has become the dominant power in the world. Players of traditional Chinese game, go, are sent to spread their superior civilization to America. During their stay in the US, they see terrorists take down the Twin Towers and plunge the country into chaos. But such predictions do not necessarily show confidence or arrogance about China's power. Writers have shown deep concern about the rapid development of China and the problems it could cause today or in the future.

In this context many science fiction stories are in fact a response to or a reflection of reality but with more imagination, said Song Mingwei, assistant professor of Chinese at Wellesley College, Massachusetts. Song said that the reality of China provides an experimental field for both utopian and dystopian sci-fi.

One example is Life of Ants, by Wang Jinkang. Set during the Cultural Revolution, the main character Yan Zhe is an intellectual youth sent to work in the countryside. Disappointed with the dark side of humanity, he decides to use ant hormones to make people altruistic, disciplined and hardworking. Yan creates a society in which he rules over his hardworking "ants" but his utopia eventually crumbles.

"My main point in writing this novel is that I don't want an almighty god to control the world because there's no way to guarantee his goodness, since eventually he would be corrupted by power," said Wang, 64. Song commented that Yan's utopian experiment essentially epitomizes the experiment of China at the time.

Holding up a mirror

While Wang delves into the past for inspirations, Han Song is very much looking ahead. Han says his job as a journalist at Xinhua News Agency gives him access to the real China.

Many writers and scholars have said that living in today's China sometimes feels surreal. In an earlier interview with the Global Times, Han said that sometimes writing news feels like science fiction.

It seems that Han is fascinated with the rapid development of China, especially transportation. In Subway, published in 2010, Han wrote about a subway train that mysteriously disappears at night and enters a seemingly endless tunnel. Passengers on the speeding train eat and mate with each other, eventually evolving into new lifeforms. It turns out that the train is part of a government subway project which is attempting to connect to the broader universe.

In 2012 he published a book entitled High-speed Railway, which begins with a high-speed railway accident. Shortly after Han finished the book, on July 23, two bullet trains collided in Wenzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province, killing at least 40 people and injuring over 200.

In the prefaces and epilogues to the two books, Han wrote about the country's huge investment in building railways and independently developing high-speed railway technologies. Since the first subway line opened in 1969, China has been playing catchup with the Western world and long seen total railway mileage as a symbol of the nation's power and revival.

Yet the rapid development that is often referred to as a miracle has left many people feeling surreal and concerned, much like Han. Reality is what inspires him. Strange, dark, and sometimes horrific, Han's novels are filled with violence, confusion and chaos. His style is often described as kafkaesque.

"There is one aspect of China that has not been written enough, and that's this kafkaesque absurdity of reality," Han told Southern Metropolis Weekly.

Writers admit that the atmosphere for fictional novels has become more tolerant. Most of their works eventually get published, although publishers are still cautious about references to the Cultural Revolution and the darkness of certain stories. Many of them have to go through several publishing houses before finding their luck.

"I think we are now at a good time for science fiction," said Yao. "We have cultivated a group of strong writers, a steady and growing fan base and we are hopeful." Circulation of his Science Fiction World magazine has grown from several thousand to 400,000 copies at its peak.

Still compared to the US where thousands of science fiction titles are published each year, only a hundred or so are published in China. Good writers are also in short supply. "For a long time people didn't believe there's a market for science fiction in China, but I think recent years have proved that is wrong," said Yao.

Unlike in some Western countries where the scientific community embraces science fiction and is involved in writing sci-fi novels, there is little overlap in China. For a long time the country viewed science and technology only as tools, with scientists not supposed to do anything other than research. Only very recently have certain scientists started to venture into sci-fi writing.

There have been other promising changes of late. In particular, as Three Body gained popularity, many publishers have shown their interest in publishing science fiction works.

However, Yao said he is worried that when seeing the market potential of sci-fi literature, some publishers might become short-sighted and too focused on profits rather than fostering good writers and stories, which remain the most important thing.

Sticking to his classic science fiction tradition, Liu is concerned that future writers and readers will see the future moving so fast that science fiction might lose its magic and appeal.

Posted in: In-Depth