Chunyun may vanish in a single generation

This year's chunyun, or Spring Festival travel rush, has started well before Spring Festival itself.

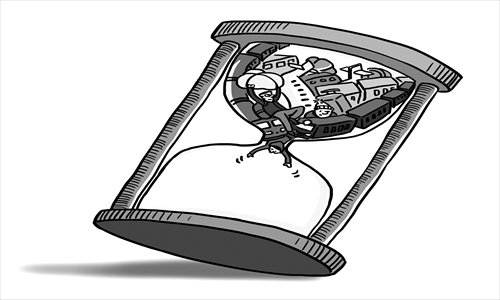

The peak of chunyun in the last few years has marked the most dramatic point in China's switch from an agricultural society to an industrial one.

Chunyun is often a source of stress. Many are anxious that they won't be able to get tickets.

Various online tips, which teach people how to sleep comfortably on extremely crowded trains, show ordinary people's frustration.

But while today chunyun seems like nothing but a source of frustration, in a few decades we might be looking back at it nostalgically.

Spending Spring Festival at home is a deeply rooted tradition which will continue long into the future. In comparison, the difficulties of chunyun appeared only in the last few decades, as Chinese society began to transform itself.

The bulk of chunyun travelers are the migrant workers who move from countryside to city, spending their working life in the metropolises but the Spring Festival with their families back in the village.

They typically reflect China's transformation from an agricultural society to an industrial one. It's these migrant workers who clog up the rails and roads in such vast numbers every year, as they struggle to collect their pay and head back to families they haven't seen for months.

It reminds me of Britain in the 19th century. The development of a variety of industries, such as spinning and shipbuilding, made people pour into the cities from the remote countryside.

With the booming population, Manchester, Liverpool and other cities rapidly became global industrial centers. By the start of the 20th century, Britain was 70 percent urban.

During this process of urbanization, the UK's transport networks suffered similar stresses, with the new railways being built to help reconcile the gulf between old and new.

Eventually those Chinese rural migrants will also set down roots in the cities and become urban residents.

As urbanization accelerates, people have more chances to work near their homes, relieving the pressure on the big cities. And Chinese families are becoming increasingly smaller, making the Spring Festival reunion easier to achieve.

In addition, technological changes and the development of logistics and transport are relieving the pressure on the roads and rails.

People can have gifts delivered online for their parents rather than bearing bulky luggage themselves.

It's possible that the peak of chunyun will end sooner than we can imagine. Within a decade or two, chunyun may become a unique memory for our generation.

We can also celebrate chunyun in another aspect. It shows the country's new freedom of movement.

In the past, police regularly expelled migrants from the cities, but today a Chinese citizen can travel virtually anywhere in the country without restriction.

Chunyun might be stressful and frustrating for the public, but it also promotes national modernization.

Chunyun has proved a stress test for China's transportation infrastructure, and thus promoted programs such as highway construction and high-speed railways, which have also made China a new world leader in global transport.

And after going through the harshest test in the world, chunyun, they are also able to provide a strong backbone for economic development.

Admittedly, chunyun exposes the problems of the hukou (household registration system). The restrictions imposed by the hukou system and the failure of locals to accept outsiders are haunting problems.

This is China's social reality, but it's not an unsolveable difficulty. A more humane system can be adopted.

According to Karl Marx, each way of social life is determined by the mode of production.

The mode of production of China has changed, and the way of life is bound to change in the future.

Each generation bears certain social and cultural marks. The memory of chunyun, I believe, will vanish in a single generation.

The author is a researcher at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn