Impossible immunization

As World Cancer Day is celebrated on February 4, it is a sad reality that potentially life-saving cervical vaccines are being kept from the Chinese mainland due to tight import restrictions and testing requirements.

Over 30 percent of cancer cases can be prevented "by a healthy lifestyle or by immunization against cancer-causing infections," while others can be detected early and then treated, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Among those, cervical cancer is currently the only type of cancer that can be prevented with vaccination and scientists are hoping to eliminate it completely.

Despite declining rates of cancer and of mortality, 200,000 deaths a year are attributed to cervical cancer worldwide with Chinese cases on the rise, especially among younger women. And seven years since the first vaccine for preventing cervical cancer was sold in the world, it is still not available in the mainland.

Vaccine options

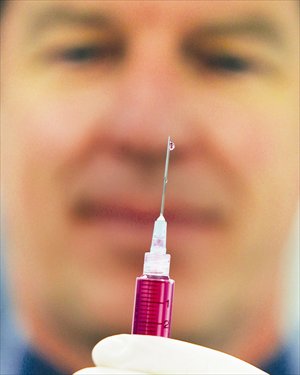

Given the particularity of cervical cancer and the potential to vaccinate against it, inoculations currently rely on two types of vaccines that target the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus, or HPV, which scientists determined decades ago as the main cause of cervical cancer.

For his work in this field, German virologist Harald zur Hausen was awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine in 2008.

In 2006 the first HPV vaccine, Gardasil, produced by Merck & Co., was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In early 2007, FDA approved another vaccine, Cervarix made by British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline.

Gardasil is designed to prevent infections from HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18, and Cervarix targets types 16 and 18. There are over 200 types of HPV and HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70 percent of cervical cancer cases.

HPV vaccines have been available in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan since late 2006. But for vaccines, or any new imported drugs, to be sold in the mainland, new clinical trials have to be performed on mainland residents. Then the drugs are re-evaluated and reviewed by the State Food and Drug Administration before they can be imported, according to regulations.

Some women who are aware of the vaccines and have the means to do so choose to get inoculated in Hong Kong. There are also many agencies that help mainland women book appointments in Hong Kong hospitals. Such procedures usually come in at around HK$3,000.

Both Gardasil and Cervarix are given in a series of three shots over the span of six months, which means women have to travel back and forth. They could also take the other two shots back home and get injected at a local clinic, but strictly speaking this is illegal since the vaccines are not yet approved for the mainland.

Zhou Zijun, professor with the School of Public Health of Peking University, said the purpose of such barriers is to protect the Chinese people while noting that every country has its own set of standards and procedures when approving imported drugs. This also serves to protect domestic pharmaceutical companies.

But many doctors argue that these regulations are too stringent and may be keeping some good medicines out. The tests done in Hong Kong and Taiwan should have been sufficient, said Gong Xiaoming, a gynecologist at Beijing Union Medical College Hospital.

He gave another example of an overseas pharmaceutical company that estimated it would cost around 100 million yuan ($16 million) to do all the clinical trials and evaluations to introduce a drug for ovarian cancer to the mainland, ultimately deciding it wasn't worth it and shelving the launch.

"We should have standards when importing new drugs, but right now it seems the threshold is too high and is preventing us from using some good drugs," said Gong.

The two vaccines started clinical trials in China around 2007. The first two stages of clinical trials have been concluded and have proven the safety of the vaccine. The third stage has been going since 2009, aiming to test the efficacy of the vaccines. But it could still take years, experts say.

In the meantime, Chinese pharmaceutical companies have also started clinical trials for domestically-produced HPV vaccines. But it is unclear when any of these will start to be sold on the mainland.

Major killer

HPV infection doesn't necessarily lead to cancer, as the human body's immune system is able to clear up some of the infections. Furthermore, vaccination doesn't guarantee that a person will not develop cancer. But studies have shown that vaccines can effectively prevent most HPV infections and about 70 percent of cervical cancer cases.

It is advised that women be vaccinated before they become sexually active. In the US, the HPV vaccination is recommended for girls between 9 and 26. In some areas, the vaccines are recommended for women up to 45 years old as well as for teenage boys.

So far the two vaccines are used in over 160 countries and regions, while students and young people in some countries get free vaccinations.

Cervical cancer ranks as the eighth most frequent cancer among women in China, and the second most frequent cancer among women between 15 and 44 years of age, according to a WHO report from September 2010.

Statistics from the Ministry of Health in 2011 showed over 130,000 new cases of cervical cancer in China each year, accounting for about one-fifth of all new cases worldwide. This translates to about 30,000 women in China dying of cervical cancer each year.

In China, cervical cancer usually occurs among women over 35 years old, especially between the ages of 45 and 49, according to research carried out by Qiao Youlin, a leading oncologist and a professor at the Cancer Institute and Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Worryingly, recent years have seen reports indicating that the disease is becoming increasingly prevalent among women in their 20s.

Most cervical cancer cases occur in central and western areas such as Shanxi, Shaanxi and Hunan, and more so in rural areas than in cities, according to a report released by the Center for Cancer Registry in January. Multiple sex partners, poor hygiene and smoking are all contributing factors to cervical cancer.

Besides vaccination, regular screenings are crucial for the early detection and treatment of cervical cancer. However, the biggest problem at the moment is that the general public, especially those in rural or poverty-stricken areas, lack awareness about the disease and the importance of getting regularly tested, said Gong.

Awareness rush

Chinese authorities have also been trying to raise awareness of breast and cervical cancer and have launched programs to promote screening.

Between 2009 and 2011, China invested over 350 million yuan to screen for breast cancer and cervical cancer among women aged between 35 and 59 in rural areas. Over 11 million rural women were tested for cervical cancer and the country aimed to screen another 10 million in 2012. Whether this program was successful remains unknown.

Despite the government's effort to promote screening, not enough is being done to ensure that the hundreds of millions of women who need the test are all able to receive it.

The commonly used screening technique, the pap smear test, detects pre-cancerous and cancerous processes in the cervical canal. It requires skilled doctors and is therefore more suited to developed countries where medical staff have decades of experience.

It takes over 10 years to train a doctor qualified to diagnose the disease from the test, but China lacks both the training system and qualified doctors, according to Qiao.

In 2008, Qiao and scientists from other countries announced in a paper published in The Lancet Oncology that they had developed a new test, named careHPV, to detect 14 high-risk types of HPV in about 2.5 hours.

It took the team five years to develop the new test, which is considerably cheaper and faster than the currently used pap smear or HPV DNA tests. It is also much easier for medical workers to master. The new test, based on the Hybrid Capture 2 technology, is designed for low-resource areas and works in environments that lack water, electricity or modern equipment.

Qiao said that the new test has just been approved by the State Food and Drug Administration last year and will enter mass production soon.

In 2011, the Cancer Foundation of China launched a research program that aims to prevent cervical cancer in ethnic minority areas. An ethnic minority county would be chosen respectively from Inner Mongolia, Yunnan and Sichuan where about 6,000 girls between 13 and 15 years of age would be inoculated with HPV vaccines.

Qiao is hoping that the medical community in China could push for the vaccines to get approved as early as possible. "We are already seven years late. Who knows how many people have been affected during that time?" said Qiao.