Bling in the 'jing

Despite Beijing's percussive-sounding dialect, the high status of SUVs on its roads and China's opening up to Western modern music, independent hip-hop appears to sit on the back burner of Beijing's modern music scene.

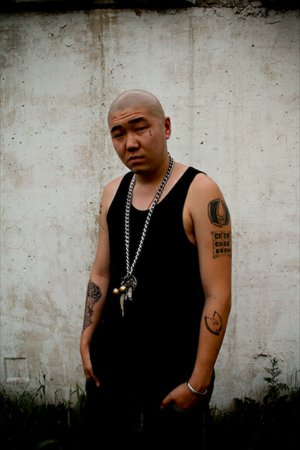

"Blending traditional Chinese music with hip-hop beats has already been tried and has failed," said Nasty Ray, 25, one of a small number of professional rap artists in the Beijing hip-hop scene. "People just weren't interested in the end. Honestly, I'm not optimistic about the future of hip-hop in Beijing."

His words come a week ahead of his supporting performance at the China premier of music documentary Mongolian Bling at Yugong Yishan on March 14.

Written and directed by Australian filmmaker Benj Binks, Mongolian Bling, part of Asian Film Week at this year's Jue music and arts festival, tells the story of how rap music transformed a generation of Mongolians as rapid urbanization took hold of the country in the '90s following a rocky break with Communism. Mongolia's capital city Ulan Bator has since filled with youths sporting baggy jeans and baseball caps, while monks and elders walk the streets in farm clothes and Buddhist robes.

Binks, 33, says he first discovered Mongolian hip-hop in 2004 while working as a tour guide on the trans-Siberian train from Beijing to St Petersburg.

He says the initial development of modern hip-hop in Mongolia was based on a cultural identity crisis facing Mongolian society at a time when Western rap was easily relatable to young people.

Themes in Mongolian rap music that appear time and again in Mongolian Bling are not unlike those that drove mid-'90s American hip-hop acts such as NWA and Public Enemy. Such themes include rundown neighborhoods, bureaucracy, corrupt legal systems and inescapable poverty.

"I think Mongolians relate to hip-hop because the situation they're facing is pretty similar to what rappers have often spoken out about strongly," he says.

Ray meanwhile admits he knows "next to nothing about Mongolian hip-hop," though he says rap in Beijing takes on an altogether a different tone, contrary to issues like poverty and cultural identity.

"It's so rare to hear anyone rap about their lives or feelings about the everyday life they see around them," Ray says. "All I hear people in Beijing rap about is how wonderful their lives supposedly are. I don't like stuff like that because I don't think the people who [rap like that] are being honest."

But Sun Xu, 28, a member of the Beijing rap group Dragon Well, says he feels positive about Beijing's future as a source of original rap music. He's keen to discover more about Mongolian hip-hop by attending the premier of Mongolian Bling.

Xu sees growth in the community as Beijing hip-hop continues to experiment with classical Chinese music. He uses Dragon Well's new album as an example, on which he says the group uses Chinese instruments and sings in distinctive Beijing accents.

Mongolian Bling also deals with the attempts of Mongolia's rap artists to come to terms with cultural change by seeking to incorporate Mongolia's musical heritage into their music.

One featured interviewee is Mongolian folk singer Bayarmagnai, 56. Said to be Mongolia's last legendary singer, Bayarmagnai says hip-hop was "originally brought over to the West from Mongolia," arguing that young Mongolian rappers should resist imitating Western hip-hop.

Ray however says Beijing's experimental phase with hip-hop that blended Western styles with traditional Chinese sounds did not prove successful.

"About 10 years ago a band named Longmenzhen used the Chinese erhu in one of their songs. People just weren't impressed by it live," he says.

Xu, who has played in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, sees clear differences between Chinese and Mongolian hip-hop, such as the distinct flow of lyrics their dialect produces.

"The best thing about Mongolian rappers though is that they keep Mongolia in the music," he says.