Fire-proof policies

Bai Weilong has been nervy since October last year, when a Tibetan set himself on fire near the famed Labrang Monastery, a few hundred meters from his office. As a community director in Labrang, Xiahe county, Gansu Province, Bai has been busy leading an anti-immolation campaign among residents. Fearing "instabilities" which might cost him his job, Bai has had 1,600 residents in the community sign letters of commitment against self-immolation.

"I spend 200 days a year maintaining stability. It's crucial we make it through March safely, as it is the most sensitive time of the year," said 31-year-old Bai. With the two sessions in Beijing, China's annual political meetings, underway and the fifth anniversary of the 2008 riots in Lhasa approaching, pressure on government workers in China's Tibetan-inhabited areas has spiked.

Letters of commitment

Since Spring Festival, Bai has been visiting homes, handing out pamphlets that introduce Chinese laws and favorable policies to residents, and telling people how the Chinese government discourages self-immolation.

"The families of self-immolators can't keep the bodies, residents are forbidden to offer condolences, and monks are not allowed to chant sutras for the dead," said Bai.

The government set up these restrictions for a reason, he said, explaining that six people attacked police when they tried to rescue a Tibetan villager on October 23 last year, after he set himself alight outside Xiahe's military headquarters. They forcibly took away the body from police to keep him from being sent to hospital, he said, with some later sentenced to years in prison for intentional homicide and stirring up troubles in January.

Apart from publicizing the trial result among villagers, the township government has been closely monitoring a group of "key targets," including monks, local residents who might have family or marriage problems, the terminally ill, and those who have expressed extreme dissatisfaction on social affairs or the government. In Bai's community, 10 "key targets" were identified, three former practitioners of Falun Gong, banned by authorities, and seven who illegally crossed the border to attend religious meetings in India.

In the letters of commitment signed between Bai and residents, Bai wrote that he would "help residents gain a better, richer life and secure a safer environment." Residents, in return, promise "not to commit self-immolation, organize or take part in illegal demonstrations or gatherings."

Stricter management

In other Tibetan regions, meanwhile, authorities have employed more restrictions over management of monasteries and monk disciplines.

"We've driven out 16 monks from Duohe Monastery, who misbehaved or violated monastery rules after the immolation of a Tibetan villager occurred nearby on October 6," said Dang, the chief of Nawu township in Hezuo, capital of Gannan prefecture in Gausu Province. Five of the monks allegedly involved in the case have been stripped of their certificates, Dang said, and the monastery management has been trying to win the remaining monks over with diversified services.

"We're planning to offer them free medical checks, building new venues where they can bathe, eat, wash clothes and read," Dang told the Global Times.

Elsewhere in Sichuan Province, at the Kirti Monastery in Tibetan-inhabited Aba prefecture, the government has tightened requirements for religious activities, and monks are required to obtain approval from a higher-level monk and the monastery management if they want a few days' leave.

More than 30 self-immolations have occurred since 2009 in Aba county. All of the immolators were connected somehow to Kirti Monastery in Aba county, a county government spokeswoman told the Global Times.

"Some were monks or former Kirti monks, and some were Kirti followers that committed immolations under others' instructions," said the spokeswoman, Yang Yanwei.

Two Tibetans, including a Kirti monk, faced 10 years in jail and the death penalty with a reprieve for intentional murder respectively after they confessed to having incited a series of self-immolations in Aba, under instructions from the Dalai Lama clique.

The Aba Intermediate People's Court ruled that Lorang Konchok and his nephew Lorang Tsering, had goaded eight people, three of whom died, to immolate themselves since 2009. They said they acted on the instructions of a monk in India who is part of the Dalai Lama clique.

"Most immolators are monks who did so for religious reasons. They cried out for the so-called independence of Tibet or the return of Dalai Lama as they were burning," Zhou Mu, a senior police officer with Aba county's public security bureau, told the Global Times, detailing his experiences dealing with more than 20 self-immolation rescues since 2009.

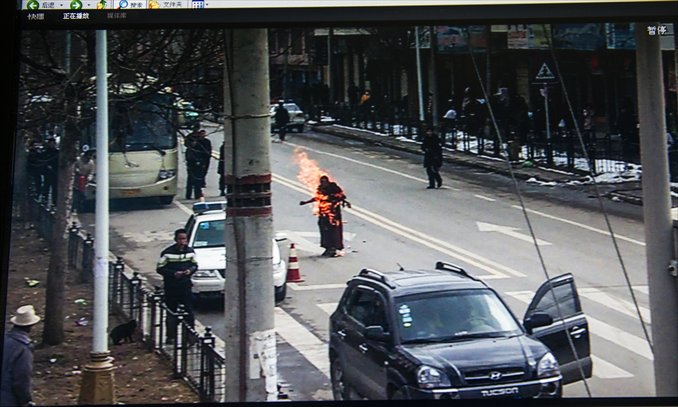

Some immolators were ordinary Tibetans, Zhou said, who had grave dissatisfactions over their own family problems or living conditions, and wanted to improve their social status and gain respect from locals through this suicidal act. A Tibetan who set himself on fire near the Kirti Monastery on February 25 this year only did it because he felt ashamed after being caught stealing. It was never easy rescuing the burning people, said the 40-year-old officer.

"One of my colleagues was attacked and injured in a rescue as a burning Tibetan strangled his neck when he tried to stop the fire, and some by-standers threw rocks at me," he said.

Tensions between monks and the government began to grow at Aba from 1998 to 2000, Zhou recalled, and peaked in 2008, when a riot started among some 300 monks on March 16, two days after the Lhasa incident.

The monks rushed out of the Kirti Monastery and attacked the government and police, Yang said. Since then the Aba county government has had four armed police vehicle stationed round the clock, and currently the Kirti Monastery is closely watched by police, with fire extinguishers placed at crossroads.

"A few residents, who were misled by the allegations of separatists, did pay tribute to the immolators and saw them as heroes. Some gave money and food to their families out of respect," Zhou said. But through recent government education by respected monks, more residents begin to realize the fact that they were fooled by religious extremists and separatists, Zhou said, who use innocent people's deaths to attract global attention and put pressure on the Chinese government.

For legal and Buddhist doctrine education, the county government of Aba has tightened control over the sales of fuel and pain-killers. Currently gas stations only open for a certain period of time during the day, with armed police patrolling nearby, and residents are required to show their ID card when purchasing pain-killers.

The county police also arrested some who took photos and filmed the immolations, as evidence showed some of them instructed the immolation, or they were informed in advance and agreed to upload the images onto the Internet.

Through the public lens

Since the beginning of March, Aba has seen its Internet access cut off and text message services blocked to prevent the spread of separatism and self-immolation information. In Gannan, residents can't connect to the Internet either, and traffic restrictions have become more frequent as police grew more careful about vehicles coming from outside the city. Nevertheless, the overall situation is changing for the better, officials say.

"Residents used to spit on me when I patrolled, but now people will greet me on the street," said Zhou Mu. The immolators who survive do not resist medical treatment, and they express regret at their actions, he said.

Gawa Gyatso, a monk at the Dazha Monastery in Aba's Ruoergai county, has been running a Tibetan-language literature magazine that publishes essays, poems, stories introducing Buddhism theories and ideas. He told the Global Times that although management tightened in March, monks still enjoy peaceful lives.

Although some residents do have a portrait of the Dalai Lama at home, most monks and laypeople see him as merely a religious symbol, say officials in Tibetan regions.

On the way from Aba to Ruoergai county, this Global Times reporter met Shanke, a 48-year-old herdsman, who had a picture of the Dalai Lama hanging in his tent. He said that he respects the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader, but doesn't agree with him on separating Tibet from China.

"I'd like to see China stand as one with Tibet, Xinjiang and other ethnic minority-inhabited areas, but I hope the Dalai Lama could return to Lhasa without political motives," Shanke said.