The buildings that became the stars

In the scores of films and television shows that have Shanghai as a setting, there are three historic buildings that constantly appear and which are fondly remembered by the city and its inhabitants - the Great World Entertainment Center (Dashijie), the Paramount Ballroom and the Garden Bridge.

The Great World Entertainment Center used to be the leading amusement venue in the Far East. It was once said that people could not claim to have visited Shanghai if they had not visited the center. In 1995 a Shanghai University survey claimed that 80 percent of the city's inhabitants had visited the center at some time.

In its glory days, people queued for hundreds of meters to get into the center. In 1946 the records show that more than 7,000 admission tickets were sold every day - the actual number of people visiting would have been higher. On one day during the 1955 Spring Festival, the center recorded 40,000 visitors. Today the center can be found at Xizang Road South and Yan'an Road East, not the same as it was once, but still a place of fun and history.

A French connection

The Great World Entertainment Center opened on July 14, 1917 in the then French Concession. It was Bastille Day (the French national day) and the 30th anniversary of the day that the center's creator, Huang Chujiu and his mother, came to Shanghai from their hometown in Yuyao, Zhejiang Province.

Huang began his working life as a doctor but being quick and good with people and having a natural flair for publicity, Huang broadened his business interests to include pharmaceutics, entertainment, tobacco and banking.

Five years before he set up the Great World Entertainment Center, Huang was involved in setting up Shanghai's very first indoor amusement park - Louwailou.

Huang proved a natural publicist, even creating a newspaper, The Great World Daily News, two weeks before the Great World Entertainment Center opened. The newspaper, of course, carried lurid descriptions of what could be seen in the center to entice even the most cynical citizens.

It was an elegant two-story brick and wood structure, with Chinese characteristics. The entrance was on what was then called Rue Palikao (today's Yunnan Road South).

The center offered the sort of entertainment that visitors might have found at a temple fair - bits of Chinese opera, conjurors, puppets, shadow plays and acrobats. As well, there were distorting mirrors, bumper cars, slot machines and roundabouts - the trappings of traditional Western fairgrounds.

But its popularity waned and the structure was torn down and a new four-story building was erected on the site in 1924 - the same building with the trademark clock face that can be seen today.

When Huang Chujiu died in 1931, the center was taken over by the crime boss Huang Jinrong ("Pockmarked Huang"). He changed the atmosphere and allowed prostitutes and drug dealers to hang out there. It became a center for dubious entertainments, gambling and crime.

In 1954, the center was taken over by the People's Republic of China government and it began a new life - very different from the days of sleaze. It was, for a while, renamed the People's Amusement Park, but later it returned to its original Chinese name, Dashijie.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), the center became a large warehouse and was renamed the Shanghai Youth Palace. In 1987 it reopened as an entertainment center under the title Dashijie. It was shut down in 2003 again for a major renovation and reopened just before the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai. Today it is back as an entertainment center offering a range of activities, fun and food for visitors.

Dancing with fame

The Paramount Ballroom, on the corner of Yuyuan Road and Wanhangdu Road was built in 1932. The imposing three-story art deco style building covers 930 square meters and was one of the leading attractions around Jing'an Temple from Day One.

Most historians believe Gu Liancheng, a businessman from Nanxun, Zhejiang Province, was the man who put the money up for the ballroom. The astute Gu noticed there were few stores and houses built in the western part of Shanghai at the time.

Gu was from a business family. His grandfather owned the only pier to service foreign cargo ships since Shanghai had opened up. When he died in 1868, the British and US consulates in Shanghai and many businesses flew their flags at half mast to show their respect.

Gu's father was a major figure in the silk business, opening several factories in Wuxi and Shanghai. His silk products won prizes at the 1926 Philadelphia international exposition.

Inheriting this sense for business, Gu expanded into different areas. He opened department stores, jewelry stores and made money in property and entertainment. He believed that dancing could be a new moneymaker - the Shanghainese of the day were rich, and loved new things and especially Western lifestyles.

He decided to build a dance hall in Shanghai where the property prices were then lower than in the east of the city. Gu believed large investments were impressive and he plunged 700,000 taels of silver into the project.

In creating the Paramount Ballroom, everything was imported - ornaments, curtains, lights, tables, chairs and the sprung floor. The decor reflected the most extravagant styles of New York's nightclubs. The ballroom featured special air conditioning that refreshed the air in the ballroom every 10 minutes.

The Paramount Ballroom was the best dance hall and the most famous of its day. In the early days most of the clientele were rich or well-connected and Westerners enjoyed the international atmosphere there.

It became as famous as its guests who included the politician Zhang Xueliang and the poet Xu Zhimo along with Charlie Chaplin who danced the night away there on a one-day visit to Shanghai.

Aiming for the ordinary

Later when other dance halls opened nearby, the Paramount had to change its marketing strategies - lowering its prices and appealing to the more ordinary citizens of the day. It became a taxi dance hall where men paid to dance with hostesses.

Some of these glamorous creatures became quite famous and there were strict regulations about how the girls should behave. Most of the hostesses were aged between 20 and 25 and the popular girls could earn up to 6,000 yinyuan (or silver dollar) a month, a fortune in those days.

Chen Manli was one of the most glamorous Paramount girls and one who became a legend with her death, which cast a tragic shadow over the ballroom. She was born to a poor family in Wuhu, Anhui Province. Her father, a barber, took the family to Japan when she was a small child. After the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45) broke out, her parents found it hard to live in Japan and came to live in Shanghai.

Chen grew into a tall elegant beauty and she could dance well. She achieved pop star fame and in a good month could earn more than 30,000 yinyuan. At one stage she was the mistress of a prominent banker. They pledged their love to each other and promised never to frequent dance halls again. Although Chen kept her promise, the banker didn't and when she discovered this she left him and returned to the Paramount.

Then in 1940 one night in the crowded dance hall, she was chatting with clients in the Paramount when she was gunned down by an unknown assailant who shot her three times. Some say she was murdered by Japanese officers because she had refused to dance with them, others say she was killed by a former lover, a Kuomintang officer, who was mortified that she had found a new man.

Still others say she was in reality an undercover Kuomintang officer and she was shot by an assassin under instructions from Wang Jingwei, the president of the Japanese-backed puppet regime in Nanjing from 1940 to 1944.

During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, the ballroom became a place most people avoided. It was near the traitor Wang Jingwei's headquarters and it became a haunt for spies and collaborators.

After the war, the ballroom reopened and in the 1950s became the Red Capitol Cinema, screening propaganda films. During the Cultural Revolution, it fell into disuse and disrepair. In 2001 a Taiwan group spent $3 million restoring the ballroom but it has never achieved the popularity it enjoyed at its birth.

Bridge over troubles

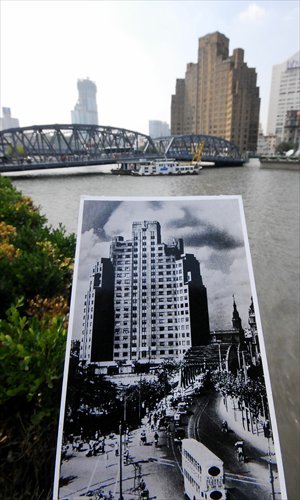

The Garden Bridge used to be a popular meeting place for lovers and today it is still a popular place for wedding photographs. Shanghai folk believed that if a newborn baby's uncle carried the child across the bridge exactly one month after it was born, the child would be brave and successful as an adult.

In 1856, British merchant Charles Wills saw that thousands of people near the Huangpu River needed to cross Suzhou Creek every day but relied on ferries. He decided that a bridge could be a profitable investment. A wooden bridge was built but the Chinese were charged a toll which created a storm in the city at the time. Most Chinese boycotted the bridge and a Guangdong man offered a free ferry service to Chinese as a protest.

In 1876, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) government built another wooden bridge near the Wills' Bridge to appease the citizens. The British called this the Garden Bridge - it was near the Bund Garden - but the Chinese called it "Waibaidu Bridge" ("the free ferry bridge").

As the wooden bridge began to show signs of age, the government built a new bridge, the first steel bridge in China, in 1906. The 52-meter bridge was opened in January 1908, with a capacity of 20 tons.

In 2007, the Shanghai government received a letter from the bridge's designer, the British company, Howarth Erskine, announcing that the bridge's expected life span of 100 years was about to end. An incredible restoration program began, which saw the bridge cut into two and taken to a shipyard to be renovated. It was reopened in 2009 with a life expectancy of another 50 years.

The adjacent hotel, the iconic Astor House, was a witness to the bridge's fortunes - the hotel having stood there since 1859. That hotel was the first place in Shanghai to have gas, electricity, a telephone and running water. It was also host to scores of famous international figures including Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell.

The bridge was not always a symbol of peace and goodwill for the Chinese. During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, every Chinese using the bridge was ordered to bow to Japanese soldiers. Anyone whose bow was considered imperfect would be forced to his or her knees, and often beaten or attacked by guard dogs.

The bridge has appeared in countless Chinese films and television shows. Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun showed Japanese troops and Chinese refugees crowding over the bridge.