HOME >> METRO SHANGHAI

From brothels to books

By Zhang Yu Source:Global Times Published: 2013-7-30 16:43:01

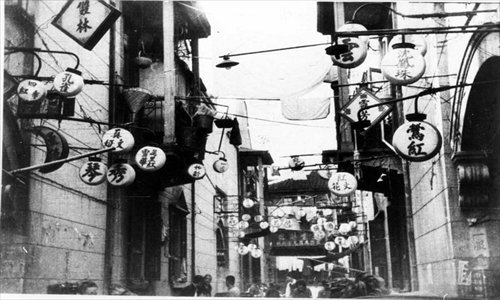

Dozens of brothels could be found in Huileli (The Lane of Lingering Happiness).

Fuzhou Road is the bookshop street, the street that leads from the Bund to Xizang Road and is today where some of the city's leading bookstores and art supply stores are to be found. It has had links with culture and literature almost since it came into being in the 1850s. Scores of newspaper offices were to be found here in Laobosanwoke Road as it was called in the early part of the 20th century. Albert Einstein once lectured there.But Fuzhou Road was also the center of the city's red-light district. Every night, brothels lit the red lanterns outside their front doors, lanterns inscribed with the names of girls like "Precious Jade" and "Pretty Phoenix." On the street, girls wearing colorful qipao greeted the men passing by.

A report in 1949 said that there were more than 400 brothels to be found on and around the street then, with over 20,000 prostitutes working in them.

The hub for vice in the area was Huileli or "The Lane of Lingering Happiness." Huileli was located in the block surrounded by Fuzhou, Xizang, Yunnan and Hankou roads - where Raffles City is found today. Back then more than 150 brothels and 600 prostitutes occupied the brick houses in the neighborhood.

The area was so famous for its prostitutes that people used to refer to prostitutes as "Huileli chickens" (chicken can be a derogatory term for a prostitute in Chinese).

Shabby area

Before the brothels moved there, Huileli was a shabby residential area where rickshaw runners, street performers, hookers and hawkers lived. In 1924, a businessman called Liu Jingde rebuilt some of the area facing Fuzhou Road, erecting 28 shikumen (traditional Shanghai-style houses with stone gates) buildings there and calling it the new Huileli, hoping to turn it into an upmarket residential area.

But few people could afford the high rents that Liu charged and instead, classy brothels moved in there, appreciating the downtown location. In 1925, the first two brothels in new Huileli opened. One was called Qin's Cloud and the other The Charming Phoenix.

Over the next 20 years, the new Huileli gradually became an upmarket red-light district while the old Huileli, the area facing Yunnan Road, became its low-life counterpart.

But prostitution in Shanghai went back a long way before then. The boat prostitutes on the Huangpu and Wusong rivers thrived during the rein of the emperors Jiaqing (1795-1820) and Daoguang (1820-50).

The boats, which the prostitutes lived on and worked in, were moving brothels and their patrons included sailors and merchants from ships and officials, scholars and businessmen from the shore.

After Shanghai opened up in 1843, foreign ships started to arrive in Shanghai and the boat prostitutes extended their services to the "red hairs," which was how they described foreigners.

As Shanghai gradually became a commercial center, prostitution moved on shore first to Hongqiao (in today's Changning district) which was for a while a major hub for vice. While some prostitutes were from Shanghai, others came from the neighboring Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. And girls from the same hometowns usually lived and worked close to each other.

The girls from Suzhou and Changshu were reportedly the best prostitutes available, next were the Shanghainese, while those from north of the Yangtze River were deemed less talented.

In 1853, the Taiping Rebellion and the Small Sword Society's uprising drove tens of thousands of Chinese refugees into the former foreign settlements in the city. The population of the former International settlement surged from 20,000 in 1855 to over 90,000 in 1865. It was these last, war-ridden years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) that saw prostitution flourish.

Escaping poverty

Many women who had lost their parents or family in the war had to resort to prostitution to escape poverty and the number of prostitutes in the settlements grew exponentially.

Chen Qiyuan, Shanghai's governor during the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1861-75) wrote: "Brothels and whorehouses grew rapidly and were protected in the foreign settlements. When I was the governor, I tried to battle these brothels, but as a local governor I had no right to interfere with what happened in the settlements. I once did a secret survey on the brothels there and there were more than 1,500 of them, while street prostitutes and call girls were numerous."

The number of prostitutes continued to expand. A survey in 1915 recorded that of the 166,000 adult women in the former International settlement, 9,791 were prostitutes - one in every 16 women were sex workers.

After the former International settlement banned prostitution in 1920, most prostitutes moved to the former French concession and that year, of the 40,000 adult women in the former French concession, 12,000 were reportedly prostitutes. The former International settlement had to lift its ban to help reduce the number of prostitutes in the former French concession.

The number of prostitutes dwindled after Shanghai's fall in 1937, but trade soon picked up again. In 1939 alone, the former International settlement issued 1,155 brothel licenses and 1,325 in 1940. Ernest O. Hauser, an American who lived in Shanghai in the old days, observed, "Prostitution was Shanghai's most prosperous business."

Prostitutes in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

Strict hierarchyIn the brothels, there was a strict hierarchy. High-end brothels were called shuyu, literally "book houses." The courtesans at shuyu were more than just prostitutes. Their main task was to entertain, to sing or perform shuoshu (talk story), a traditional Chinese art where the the performer recites a story with dramatic flare and expression. To become a courtesan at a shuyu, a girl had to have been trained by famous tutors and should have been able to recite several stories by heart.

Qing Dynasty historian Xu Ke (1869-1928) compiled his Extracts From Notes and Newspaper Articles of the Qing Dynasty and devoted one volume to the lives of prostitutes in Shanghai.

According to Xu's book, "selling sex was strictly banned in shuyu and the wildest thing a shuyu girl could do was to accompany their patrons at the dining table and persuade them to eat or drink." But even during these occasions, they should be self-restrained.

To distinguish themselves, shuyu usually hung special lanterns on their front doors, with their names inscribed on them. Once a patron entered a shuyu, the madam would come out to welcome the patron and introduce the courtesans who were available.

If the patron picked a girl, the madam would order a dinner table to be set up in the hall or in a restaurant, and asked the girl to accompany and please the patron. If the patron couldn't find a suitable girl, he just paid for his tea and left.

The shuyu courtesans charged a lot and usually only high officials and rich scholars could afford such entertainment. Each song or story cost a silver dollar. The more performances a man enjoyed the higher the cost. Although shuyu girls theoretically didn't provide sex services, a man could buy a girl to become a wife or concubine. But this cost an astronomical amount and few could afford this.

Another type of brothel was the changsan house and a girl working here was called a "changsan" - they charged 3 silver dollars to accompany a man to dinner (san means three). Changsan girls could sing and tell stories like shuyu girls but patrons could discreetly ask for sex.

Changsan were not only expensive but also required patrons to have connections, without which he wouldn't know how to find one. The prices were extravagant. Just two rounds of mahjong with a changsan, for example, costs 12 silver dollars, and during festivals, patrons needed to give hongbao (red envelopes) to the changsan girls to maintain their relationship. A man wouldn't dare walk into a changsan house if he didn't have a large amount of cash on him.

The high-end prostitutes could choose their clients. Xu's book mentions a prostitute called Yunshan who had a special liking for the literati: "She was so famous that rich people parked their cars in front of her house every day, hoping they could glimpse the beauty. But Yunshan only accepted men of letters and despised philistines. If a scholar held a party, she would attend and would not ask for a penny. But if someone she disliked invited her, she wouldn't go even if they offered a fortune."

A beauty contest

Each year in Shanghai, there was a contest for the shuyu and changsan girls, which focused mainly on beauty but also considered their skills in singing and performing. The top-rated girls were given the names of flowers in the annual huabang ranking (the flower ladder).

Although the contest could be traced back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), it declined and went underground in the Qing Dynasty as the government officials and men of letters, who usually organized the contest, were banned from being involved in prostitution. But at the end of the 19th century, it was revived in the former foreign settlements where prostitution was legal if a brothel had a license.

In 1877, 28 girls were named the flowers of Shanghai. The winner, Wang Yiqin, was described in a poem: "Wang is as pretty as a peony. Her beauty is so unique that no one can rival her in elegance and grace."

In 1888, 16 girls were named Shanghai's flowers. "The top flower is Yao Rongchu, from Ripple House. A fragrance surrounds her. She is as charming as peach flowers and her complexion is like pink clouds."

If shuyu and changsan houses were the pleasure haunts for the upper class, it was a different story at the other end of society. Prostitutes in these brothels had usually been bought from poor families and had no choice of clients.

They did not charge a lot and were constantly pressed to solicit more clients no matter how they felt. Some were known as the "wild chickens" - they had to go on the streets to solicit customers themselves. If they failed, they had to face the anger of their pimps.

Other prostitutes worked in hotels, opium dens and on boats. They had no control over their own lives, constantly faced the threat of venereal disease and it was almost impossible for them to ever settle down to a normal happy family life again.

Xu tells of a prostitute called Li Peilan, who fell in love with the son of Shanghai's local governor Mo Xiangzhi. Secretly they agreed to marry without telling their parents. But when a Shanghai man tried to buy Li for himself, they revealed their love to the governor who rejected them both.

The son died of sickness and Li was in mourning for three years before returning to work as a prostitute. The governor never acknowledged her as the wife of his son.

Several prostitutes became concubines for wealthy men but Xu noted that many of them later returned to prostitution - their relationships were not based on love but on vanity and lust for physical beauty.

Closing down

Brothels were not immediately banned after the founding of the People's Republic of China. In 1949, the government issued regulations for brothels, banning brothels from serving government officials and soldiers and ordering brothels not to force prostitutes to provide sex if it was against their will. Opium was banned inside brothels.

Many brothels began to close with the new strictures. By 1951, only 72 brothels remained in the city. Brothels in Shanghai almost completely disappeared until the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) when underground brothels began to open again.

From 1951 the government opened reeducation institutions to teach former prostitutes skills, treat them for venereal diseases and prepare them for society. Until 1958 the city's Women Reeducation Institution in Taixing Road had accepted more than 7,500 former prostitutes. Some 2,600 were sent to labor on farms in Anhui and Jiangsu provinces, 1,500 returned to their hometowns, and 2,000 went to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Gansu Province to work. In 1958, the reform institution itself turned into a State-owned factory and moved to Gansu Province.

Posted in: Metro Shanghai, Meeting up with old Shanghai