Economic suicide biggest threat to China

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

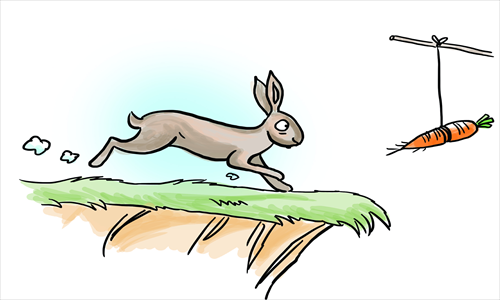

China cannot be murdered, therefore it must be persuaded to commit suicide. This summarizes the geopolitical situation as seen by Western anti-China circles.

It encapsulates that China's national revival has now reached a point where no external forces are strong enough to prevent China's rise. The US remains militarily stronger, but China's strength is sufficient that US losses in a war would be so great even neoconservatives do not advocate it.

US authorities can try to murder Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, and possibly in the future Latin American countries, but China is too strong.

This does not mean Western anti-China circles have given up. If it is impossible to murder China, perhaps it may be possible to persuade it to commit suicide? This idea might appear ludicrous, but actually the US has already succeeded twice, with Japan and the USSR.

From the 1970s, confronted with dramatic Japanese economic growth, the US persuaded Japan to overvalue the yen, cut investment to slow growth, and implement ultra-low interest rates after the Wall Street crash in 1987, allowing Japan's capital to flow to the US and safeguarding the latter's financial system, while Japan itself suffered the "bubble economy" which exploded in 1990.

In the 1990s, the West persuaded the USSR not to follow China's successful economic reform, but to undertake "shock therapy" - total privatization of state companies.

The result was the greatest peacetime economic collapse seen in a major country in modern history. Russia's GDP fell by 40 percent, male life expectancy dropped by seven years, and Baltic and Central Asian independence movements destroyed the USSR, reducing Russia from leading a state of 288 million people to one with a 143 million population. Vladimir Putin accurately described this as "the greatest geopolitical disaster of the last century."

China is harder to persuade to commit suicide. Unlike Japan, it cannot be blackmailed via military dependence on the US. Unlike the USSR, China is not pursuing an economically adventurist policy of seeking military parity with the US on the basis of a GDP only 40 percent as large.

But the West understands its leverage points. Ordinary Chinese citizens are economically tied to their motherland, but the rich can take wealth abroad.

The fate of State-owned enterprises and many productive private companies is tied to China's economic revival, but some financial groups can get rich even amid chaos, while certain professionals can be offered jobs such as well-paid professorships at US universities.

Therefore, a comprador bourgeoisie exists with support among those Chinese professionals whose highest ambition would be a US green card. If China cannot be murdered, these may be used to persuade China to commit suicide by adopting policies damaging itself.

After experience with Japan and the USSR, the US government knows accurately which policies those are.

Investment is the most important factor in economic growth, so China's economy should be slowed by reducing investment, as was Japan's.

An overvalued currency slows an economy, so constant pressure should be exerted for the yuan's exchange rate to rise excessively.

China's State-owned companies are its economic core and key to its ability to calibrate macroeconomic policy, so they should be weakened or destroyed, as with the USSR.

Moreover, to attempt to conceal that China's rise in living standards is the fastest ever seen in a major country, billions of propaganda dollars should be spent exaggerating out of proportion every real problem inevitably arising in China's rapid development.

It is therefore to radically misunderstand the situation to imagine the biggest threat to China is US aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

The biggest threat to China is forces within it trying to persuade it to commit suicide by adopting policies inevitably derailing its national revival.

Such processes can easily be followed from outside China. But while murder involves another person, suicide is a personal decision. The world's most important question is whether China can be persuaded to commit suicide or not.

The author is former director of London's Economic and Business Policy and currently a senior fellow with Chongyang Institute, Renmin University of China. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn