Bringing new words home

Early last century the translations of great books were often the only windows where Chinese people could view the rest of the world. Classics like Anna Karenina, War and Peace, and the plays of William Shakespeare were, for most, the only way Chinese people could learn about foreign cultures and the lives of people in other countries. In those days only a handful of Chinese people spoke another language and fewer still could translate books. As one of the few Chinese cities which opened to the world after hundreds of years' of the Qing Dynasty's (1644-1911) closed-door policy - which also closed visions and minds - Shanghai cultivated a group of acclaimed translators.

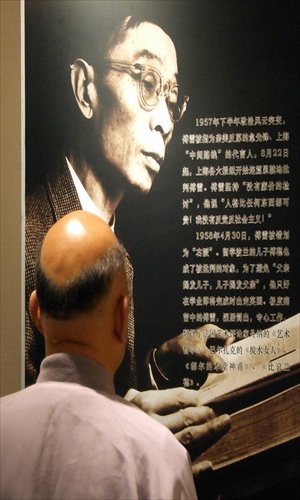

One of the most famous of that time was Fu Lei (1908-1966), who was born in then Jiangsu Province's Nanhui county (now the Pudong New Area of Shanghai). In the 1960s, Fu was made a member of the Society of Balzac Studies in France for his extraordinary contribution in translating Balzac's works.

A determined mother

Fu was born into a prominent family which had fallen on hard times. Tragedy struck when Fu was just 4 years old and he lost his father, two brothers and a sister in the same year. But his mother was determined that her sole remaining child would succeed in life.

Fu's mother Li Yuzhen was an influential woman and brought her son up strictly. In 1920 when he was 12 she sent Fu to modern downtown Shanghai to be educated. Fu, however, was far from an ideal student and his argumentative and abrasive personality saw him upset teachers and fellow pupils in a variety of schools. He never received a graduation diploma from primary, junior high or senior high schools. His difficult personality remained unchanged throughout his life. As a student he participated in the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (a massive student movement that endorsed nationalism and objected to China accepting foreign domination), and during the Northern Expedition (1926-27), Fu's mother made him leave school, fearing the Kuomintang would arrest him.

He maintained his fervor to change things in China and in 1927 he decided to go and study in France (he had learned some French at Collège Saint Ignace, today's Shanghai Xuhui Middle School). He boarded a ship on December 30 that year and one month and five days later he set foot in France, aged 19.

From 1928 to 1931, Fu studied literature but he found himself more interested in art theory and criticism. In his four years abroad, he visited Switzerland, Belgium and Italy, and other European countries spending time in famous art galleries and devouring some of the classic works of art on display. In Paris he befriended the Shanghai artist Liu Haisu, who was studying in the city.

He began publishing articles about art and artists, writing about da Vinci and his Mona Lisa, Monet, Cézanne, Rembrandt, Rubens, Michelangelo and Raphael. He translated a series of pieces for Chinese journals and magazines, including Romain Rolland's biographies of Beethoven, Michelangelo and Tolstoy.

These articles and translations were his early contributions to China. He also introduced to China some of the aspects of Western art and philosophy during the first 20 years of the 20th century. His own belief that the study of literature involved the study of art and aesthetics was the background to his exposition of Western art.

When he returned to Shanghai in the autumn of 1931, he taught art history and French at Liu Haisu's Shanghai School of Fine Arts and started to translate and write about French literature.

As well as the works of Balzac, he introduced Chinese readers to Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe and Voltaire's Candide.

However, despite his great contribution to literature he was attacked and harassed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). He and his wife Zhu Meifu committed suicide together on September 3, 1966.

Widely acclaimed

Some of the greatest literary gifts to the world from England are the plays of Shakespeare. Zhu Shenghao (1912-1944) has been widely acclaimed for his sensitive and accurate translations of the Bard's works.

Zhu was born in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province and lost his mother when he was 10 and then his father when he was 12. The deaths of his parents affected him deeply and led him to become somewhat reclusive and antisocial. He studied Chinese literature and English at the Zhijiang University in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. After graduating in 1933, he took up a position as an English editor with the publishing company Shijie Shuju.

There he helped compile an English-Chinese dictionary. Outside of work he wrote poetry, which was destroyed in later conflicts, along with essays and articles for newspapers and journals.

In the spring of 1935, he started to translate a complete collection of Shakespeare's plays. Unlike the Oxford editions, which arranged the plays in order of writing, Zhu recategorized the plays as comedies, tragedies, histories and dramas. When the Japanese took over the city in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45) he had to move from one shelter to another. Even though he became seriously ill he continued translating no matter what was happening around him. Before the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 he had completed the translations of 31 of Shakespeare's plays and had published 27. In the hectic reshuffles as he was forced to move from place to place during the conflict he sometimes lost some of his work but once he found a new home he retranslated the missing sections.

Even when he was very ill and poor he continued translating, working with two dictionaries and an English edition of the plays.

He died of a respiratory disease at the age of 32 on December 26 in 1944, leaving his 1-year-old son and his young wife Song Qingru, who was also a translator and Shakespeare scholar.

The Russian problem

Although several European authors were being translated by the end of the Qing Dynasty, few Russian works were available in China. Wu Tao had studied in Japan and translated some of the works of Lermontov, Chekhov and Gorky but he translated these from Japanese translations. No one at that stage could translate Russian books directly.

In the early and middle 1920s, many Russian books were translated into Chinese and appeared in magazines and periodicals. Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov and Pushkin were introduced to China this way - but most of these works were translated from English versions.

Russian literature was proving popular and a proper translator was desperately needed. He arrived on the scene as Sheng Junfeng but became best known throughout the land as Cao Ying, China's leading translator of Russian literature.

Sheng was born to a wealthy family in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. He was greatly influenced by the writer Lu Xun and early on became interested in Russian literature.

In December, 1937, after war broke out, 14-year-old Sheng and his family moved to Shanghai where he bought a complete collection of Lu Xun's articles with his pocket money. From then on he became obsessed with literature and translation.

His first Russian language teacher was a Russian housewife who had advertised in a newspaper and he spent his pocket money on his weekly lessons with her. His only text book was a Japanese-Russian dictionary and he studied at night and on the weekends. He was given a boost when he met an underground Party member Jiang Chunfang (who later founded the Encyclopedia of China) who offered to teach him Russian more formally.

In 1941 Sheng gave himself the pen name Cao Ying and officially began translating. His teacher Jiang Chunfang helped launch the Chinese magazine Soviet Literature and Sheng became a contributor. For the next 60 years Sheng worked as a translator but there were ups and downs. When relationships between the former Soviet Union and China soured, literary contact between the two countries was discontinued and during the Cultural Revolution, Sheng almost lost his life after being detained and tortured. When the Cultural Revolution ended, he resumed his work, refusing an offer by the Publicity Department of the CPC Shanghai Committee of a job as editor-in-chief for a publisher. In doing this he forfeited a pension and other bonuses but said he was happy to get back to translating.

At the age of 55, he began translating the complete works of Tolstoy, a task that took him some 20 years. In the novel War and Peace alone there are more than 550 characters and Sheng read the book three or four times so he would be able to define each character clearly. His translation of the complete works of Tolstoy was published in July 2004.

Sheng first visited the USSR in 1985 and made a special pilgrimage to see the home of his favorite author. In 2006, he was admitted as an honorary member to the Russian Writers' Association.

Compiled by Du Qiongfang