Found in translation

To the surprise - and delight - of Anne Cheng, a French-Chinese sinologist from the Collège de France, when Yantie Lun (The Salt and Iron Debate), an ancient Chinese text written during the Western Han Dynasty (206BC- AD25), was translated and published in France three years ago, it aroused great interest among a group of modern French economists.

Elevated to the rank of a Chinese classic, Yantie Lun records the responses exchanged in 81BC during a Chinese Imperial Council meeting whose agenda was to discuss the issue of the salt and iron monopoly. A debate ensued over the right way to govern between proponents of the school of Legalism and Confucian scholars and sages.

(From left) Anne Cheng, Marie-José d'Hoop and Marc Kalinowski Photos: Courtesy of Consulate General of France in Shanghai

"This text not only constitutes a firsthand testimony of that bygone era's lifestyles and political mores, but also a mine of timeless wisdom on the art of how to manage a society," Cheng said. "However, who could have imagined that this ancient Chinese book could inspire a group of modern non-Chinese who are not studying Chinese language or Chinese history."

Cheng told us that after reading Yantie Lun, French economists marveled at ancient Chinese people's modern and sophisticated understanding of economics.

This surprise success was a validation of sorts for a publishing project that Cheng is participating in as a chief editor.

Three years ago, under the invitation of Les Belles Lettres, a French publisher that specializes in publishing bilingual ancient classics, Cheng and a group of French sinologists, including Marc Kalinowski from Paris' prestigious École pratique des hautes études, organized a committee.

With the frequency of four books a year, the committee plans to translate and publish bilingual editions of classical Chinese texts, annotated with detailed notes and explanations. The scope will cover different fields, ranging from philosophy and politics to science and medicine, and even cooking and recipes.

According to Marie-José d'Hoop, a publisher at Les Belles Lettres, they have published 12 classical Chinese texts thus far, including Yantie Lun.

"We don't have an exact number of how many books we will do in the future, but now at least, another 15 are on the agenda," the publisher told the Global Times.

Among those already published and due-to-be published are the very well-known, like Lunyu (The Analects) and Daode Jing (Laozi), which have been translated into French many times, as well as texts that have never before been translated into French, like Guanzi and Wenzi.

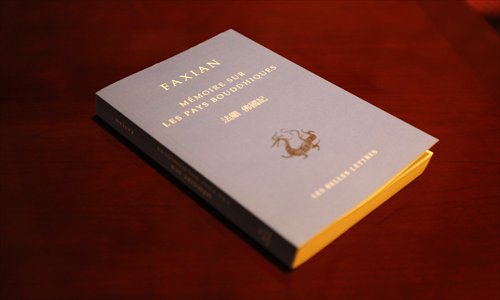

One of the books edited by the French sinologists

Kalinowski told the Global Times, "It also needs to be noted that what we do are books written in classical Chinese, which not only refers to classical Chinese texts written by Chinese people, but also by non-Chinese, like Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, since those countries had learned a lot from ancient China very early on."

One of their published translations is Japanese scholar and poet Fujiwara no Akihira's (989-1066) short essay collection in classical Chinese, Shin Sarugaku Ki (An Account of the New Sarugaku).

Both Cheng and Kalinowski believe that France has had a strong tradition of scholarly interest in China since the 17th century, when the first French Flemish Jesuit, Nicolas Trigault (1577-1628), visited China.

Cheng told the Global Times, "Even in the 19th century, when the whole of Europe tended to reject China both in their self-assertion of European identity, but also in their colonial contexts, France became the first place in Europe to establish a professorship for Chinese study, which was by the Collège de France in 1814."

"Next June, in 2014, the college will celebrate its 200th anniversary," she added.

As time moved on, many French people continued to show an interest in Maoism and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), and now in contemporary China.

Kalinowski told the Global Times that thanks to modern technology, French people can easily keep up to date with what is happening in present-day China and you can also find the writings of Mo Yan and Han Han in the bookstores of Paris.

"And in those bookstores, you can probably also find French translations of various classical Chinese texts, like Lunyu and Laozi," he said. "However, very few of them are printed in bilingual form and accompanied with detailed, comprehensive notes and explanations," Kalinowski added.

Cheng told us that there has also been a revival in the study of classical Chinese texts among the Chinese public. During their recent trip to China, they looked at the Chinese market for their series of books.

As sinologists, both Cheng and Kalinowski studied at Fudan University in the 1970s. They told the Global Times that at that time, research of classical Chinese was tightly controlled by the government.

"We were not allowed to get in touch with classical books except fajia," Kalinowski said, referring to Legalism, a school of philosophy from the Spring and Autumn (770-476BC) and Warring States (475-221BC) periods, emphasizing strict obedience to the rule of law.

"And many of the published academic books in this field were also very politically oriented," Cheng added. "The situation certainly has changed a lot now, and today, not only in China, but much sinology research in the West has also got funding support from the Chinese government."