Life after prodigy

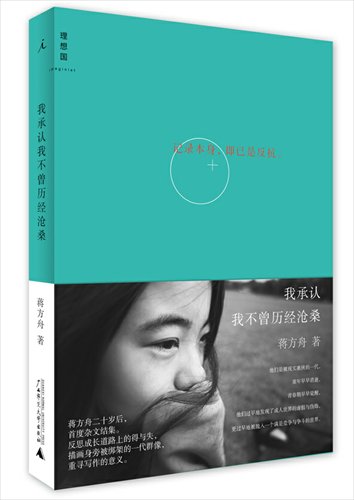

Jiang Fangzhou writes more candidly than ever in I Admit That I Haven't Lived. Photos: Courtesy of Guangxi Normal University Press

When looking back at our past, the younger version of ourselves sometimes excites us, sometimes embarrasses us. As we grow older, we tend to rethink or even regret what we did. Life experience shapes us into a different person.

This also holds true for Jiang Fangzhou, who was hailed as a gifted child when she published her first book at the age of 9 in 1999. A well-known writer by her teenage years and then a student at Tsinghua University, Jiang is now the deputy editor of New Weekly - at the ripe old age of 24.

With so much attention put on her precocious pursuits, Jiang had a lot of eyes watching her as she made the transition into adulthood. Despite her reputation as a brave and even rebellious writer, Jiang is now admitting that she "has not lived."

After going five years without publishing any new books, Jiang returns with I Admit That I Haven't Lived. She looks back on what she gained and lost in her unique adolescence and tries to say goodbye to her prodigy past.

With age comes wisdom

Born in 1989, Jiang has already penned 10 books. She was also a columnist for many publications when she was a teenager.

When Jiang first started publishing her books at such a young age, people questioned whether her mother was the ghostwriter. When she was accepted by Tsinghua University, people questioned whether the university lowered its enrollment standards to let her in. When she became the deputy editor of New Weekly right after she graduated from Tsinghua, people questioned her qualifications for that, too.

The biggest reason this young woman attracts so much controversy, though, may be her candid writing style. She's never concealed her desire to be famous. She wrote boastfully in one of her earlier books that "early ripening apples sell well" and "I have high standards about finding a boyfriend: He has to be as rich as Bill Gates, as handsome as Chow Yun-fat, as romantic as Leonardo DiCaprio and as strong as Viagra." Her sophisticated yet unconventional way of writing inspired many debates - all centered around her.

All the fame and all the disputes don't seem to ruffle Jiang's feathers. However, in an interview with the Global Times, Jiang revealed that "the older I grow, the more fragile I feel."

She said she did not fear those judgments when she was a child and had the feeling of proving herself to those who did judge her. The more negative the voices, the stronger she wanted to be.

"I used to think all those people who hated me and said bad things about me were bad people," Jiang said. "But now that I've grown up, I can totally understand them. You can't judge one person as a bad guy just because he or she questioned you."

Compared to her previously sheltered life in a small city in Hubei Province where she was insulated from insults, Jiang now can easily view all the hurtful comments online herself - and she has found that she can be easily hurt.

The 'post-1980' attitude

On the cover of her new book, she wrote "recording itself is a resistance." This is also the main idea of the second chapter.

When she came up with this phrase, Jiang said she was not entirely sure what to "resist." Was she resisting age, resisting society?

"Then I came up with a perfect answer: To resist anything that stopped us from being ourselves," she said.

Her attitude and her experiences are representative of the "post-1980" generation, which used to be questioned, criticized and once regarded as a hopeless, self-absorbed generation in China.

Post-1980s were once judged for being too self-centered and rebellious. In recalling her school days, Jiang addresses these ideas by comparing and contrasting her own generation with those preceding it.

Unlike those who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s with strong collective memories shaped by political and historical events, post-1980s don't have these same shared experiences. That is one reason, Jiang said, that they are more focused on themselves and disregard conventions.

Jiang shared that she was once concerned that her age cohort was more pessimistic, but when she finished working on this book, she found her generation to be a hopeful one.

"You have the space to make choices," Jiang said. "The last generation just accepted the rules of this world, whereas we see ourselves as the ones who make the rules."

Yan Lianke, an influential Chinese novelist, praised the young writer, who is a friend of his.

"Her understanding about literature is different from our generation," said 55-year-old Yan. "Her understanding has already surpassed our generation. This book can end the last generation's writers' doubts about the newer generations."

Farewell to labels

Jiang admits that in the five years she wasn't putting out new books, she encountered writer's block. She expressed her frustration many times when she was in college. The excellence of the other students made her doubt herself.

Ever since she published a book at 9, Jiang had been coming out with a new book every year.

"One day I suddenly doubted the meaning of publishing new books," she said. "Am I doing it for others or for myself?"

Even in her break from publishing books, Jiang never stopped writing, and turned to other ways of creating.

That's why in this book, she includes a collection of all the articles she wrote over the past few years. She adds postscripts to each piece about the circumstances that led to the article, and what she thinks now when she rereads it.

Though far from her first effort, this book represents something new and different for Jiang.

"Many messages from readers touched me deeply," she said. "They didn't see Jiang Fangzhou in this book. They saw themselves."

And for Jiang personally, I Admit That I Haven't Lived marks the end of her childhood. Farewell to the child prodigy, farewell to the teenage writer, farewell to the Tsinghua genius, farewell to all the labels.

"When I finally hung up all my titles, I felt I finally got a book that doesn't embarrass me," she said.