On the edge

Karen Liao suffered rejection from her family twice after coming out as gay and then again as genderqueer. Liao is dedicated to the study and equal rights movements of the Chinese transgender community. Photo: Li Hao/ GT

Acid Chen hardly stands out among the crowd of young female customers at a café on the campus of Peking University. With her tall, slender frame and straight hair falling below her shoulders, Chen's dimples emerge each time she smiles. She reaches for a pocket in her denim shorts fashionably worn over long winter leggings and pulls out a box of pills.

"These are the estrogen pills I was talking about," she explains in a low voice. "I take them daily." Chen, 24, was born male but identifies as female. For nearly all her adult life she has felt trapped in the wrong body.

Society hasn't helped smooth her transition as a transgender woman, with daily discrimination a constant reminder of the long road ahead she and other gender non-conformists face for equality.

Beyond the gender divide

Today marks Transgender Day of Remembrance, a day to memorialize those killed from transphobic violence. Although such incidences are rare in China compared to the rest of the world, Chen said the day is important to her because it raises awareness about the "T" often overlooked when discussing lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights.

"The key difference between the LGB and T is that the former are more concerned about partners they want, while the latter is more concerned about determining who they actually are. I gradually realized that the most important thing is not who my partner is, but who I am," said Chen.

Chen was born and raised with traditional family values in Beijing. In 2006, she left home to attend university in Changsha, Hunan Province.

Although she had tussled with gender issues for some time, it wasn't until Chen stumbled upon an online forum that she learned about transgenderism. Much of what she read resonated with her, and cemented her resolve to become a woman.

"During high school and university I felt very confused. I used to think I was gay, so I tried to chase after boys but it didn't feel right. I later thought something must be terribly wrong," said Chen, an electrical engineer who plans to undergo sexual reassignment surgery next year.

Chen's turning point came during a train trip in 2006 to the Tibet Autonomous Region. Alone with her thoughts, she realized she wanted to wear women's clothes. She bought a pink T-shirt with cute bow ties on the shoulders - a move that was met by ridicule by her classmates.

Undeterred, she continued exploring her feminine side by buying a conservative outfit: a white hooded sweater, jeans and red canvas shoes. It was the start of her wardrobe's transformation, with women's clothes gradually replacing her male outfits.

Struggle for support

In May 2011, Chen returned to Beijing on a business trip where she was met by suspicious looks from her mother over her new feminine look. After a 15-minute standoff, Chen mumbled: "I want to change sex." Like many transgender people who open up to their family, Chen was met with denial and then rejection.

"We can never talk it through. We always argue," Chen said of coming out to her parents. Fortunately, Chen's grandmother showed support. "I think it's because [grandparents] don't have so many expectations for their grandchildren compared to parents," Chen said.

Chen's confidence to be more open about her transgender identity grew after getting in touch with support networks including the Beijing LGBT Center and Aibai Culture and Education Center, the latter an NGO she volunteers for that advocates for LGBT rights.

"Everybody has a comfort zone, but gender isn't clear-cut. As long as you're in your own comfortable position, everything is good," said Chen.

Rather than urging pride rallies or public demonstrations that raise awareness about transgender rights, Chen said the "best survival technique for transgender people is to be low key."

"I know many senior executives and scientists who are transgender. The premise of being 'invisible' is your appearance [as a woman] can pass among others," she said.

New appearance, new persona

Chen's transformation hasn't been an overnight process. It began in February 2008 when she decided to grow her hair long.

"You face many choices [as a transgender person] including fashion, hairstyle, voice pitch, hormones and surgery. I chose to work on my hairstyle first because hormones are not for beginners. Changing fashion [to women's clothes] was unrealistic while at university," she said.

Around a year ago when she began taking estrogen pills as part of hormone replacement therapy, Chen began considering sexual reassignment surgery. She hopes to have it done in Thailand in a move that looms as her final step toward becoming a woman.

Chen hasn't told her family about the operation. "I guess they already know it coming at some point, but it doesn't matter. I'll be cool regardless of how they react. I don't imagine that they will interfere with my life," she said.

The director of the Guizhou Qiancheng Lesbian Community, surnamed Liu, was born female but identifies as male. Photo: Courtesy of Liu

Legal, medical woes

China's first draft guidelines on sexual reassignment surgery proposed candidates must show an agreement from police to change their sex on their identification cards once the procedure is complete, according to a statement on the Ministry of Health's website in June 2009.

While such requirements might persuade people like Chen to head overseas for surgery, many transgender Chinese are willing to go under the knife at home. Sam (pseudonym), a 24-year-old who was born female but identifies male, had his breasts removed at the Shanghai People's Liberation Army No. 411 Hospital in January.

Forging an authorization permit on behalf of his parents, Sam went alone to the hospital and underwent the surgery. Sam said his mother accepted him having a girlfriend, but opposed the surgery.

"The total cost was about 150,000 yuan ($24,623), but it took a long time to recover. Doctors warned me it would be bad for my long-term health," Sam said.

Sam attended the China/Asia Transgender Community Round Table summit organized by the United Nations Development Programme and held in Beijing on November 10.

The talk included transgender community leaders from around China and the world who discussed health and social issues as well as efforts to advance rights and battle discrimination.

Sam pinpointed health insurance as one of the most pressing issues for transgender people like him who have had surgery to adapt to their new gender.

One of the biggest issues in China facing transgender people is that they are deemed to be suffering an "idiopathic disease," according to Karen Liao, program director at Beijing-based LGBT support network Common Language. "The desire to change sex is pathologized, and changing one's body is seen as a 'treatment' of the 'disease,'" she said.

Sam said most transgender-related surgeries are performed in a hospital's dermatological or plastic surgery department. To change the sex listed on a transgender person's identification card in China, a note from a doctor saying sexual reassignment surgery was performed to correct androgyny must be presented to police, said Sam.

"We have to treat ourselves as lab rats because there is no medical guidance on hormone replacement therapy given by doctors," said Sam, who said he and other transgender people must instead rely on psychologists.

Transgender Chinese also face problems having their educational qualifications recognized, which can hinder their ability to find employment. "The gender on your degree can't be changed, which causes problems when it comes to job-hunting," Sam added.

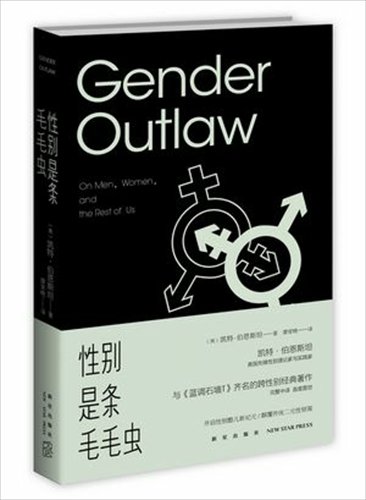

A copy of the Chinese version of Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women and the Rest of Us, translated by Karen Liao. Photo:Li Hao/GT

Blurring the boundaries

Like many other transgender people, Sam prefers to be categorized as "gay" rather than transgender. It's easier for people to assume he is a lesbian rather than coming out and telling them he was actually born a woman, Sam said. "I feel like I am drifting between genders. Society is already unfair, and transgender people are already invisible within the LGBT community," he said.

Another participant at the talk, who only gave his surname as Liu, admitted he had only learned he was a man trapped in a woman's body a few months ago. Liu, who heads the Guizhou Qiancheng Lesbian Community, made his revelation after mingling with transgender friends.

"I've considered myself different from other girls since childhood. I liked girls, but wondered why I was one. I denied the state of my body and wanted nothing more than to be a boy," said Liu, who has limited options because he claims people in Guizhou "aren't ready to accept people who have undergone sex changes yet."

Liu lingers in a gender "no man's land." Unable to undergo surgery for fear of exclusion, he wears tight corsets to suppress his breasts and avoids looking at his body while showering. He shies away from intimacy and uses male restrooms, but still lists his gender as "female" when filling out forms.

Liao, who has a master's degree in anthropology, recently published the Chinese version of Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women and the Rest of Us (1995), a transgender coming-of-age story by American author Kate Bornstein.

"I always knew about the fluidity of sexuality, but I didn't realize the fluidity of gender itself before reading the book three years ago," said Liao, who was born female but identifies as neither male or female. Liao recently came out to his parents for a second time, having earlier told them he was a lesbian. Neither time was well-accepted.

"It's a process of questioning myself. Anyone and anything born can be questioned, deconstructed and rebuilt," said Liao.