Move and chat

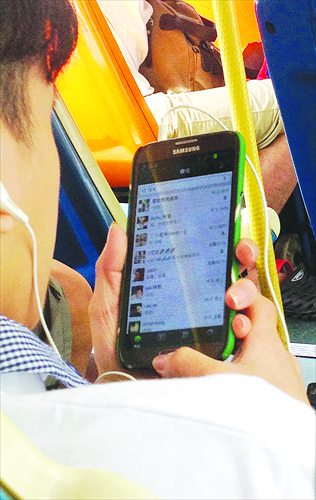

A woman uses WeChat on her smartphone while taking the bus in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province. Photo: CFP

Qiu Xuyu, a corporate law attorney in Guangzhou, is a busy man, not just with his day-to-day work, but also on social media. As well as being on Weibo, he also uses three smartphones to engage with his over 300 WeChat groups.

A mobile messaging service application, WeChat seems to be quickly overtaking Weibo in popularity. Over the past four years, Weibo dramatically changed the way people engage in public discussions and activism. As Weibo seems to be declining in activity and facing stricter monitoring, some are wondering, could WeChat be the next big thing?

In the two years after it was launched in January 2011, the number of users on WeChat has reached 300 million. Some industry reports have put the number of users today at over 500 million, including about 100 million overseas users.

It took Weibo, launched in August 2009, over three years to pass 300 million users.

Unlike Weibo, which is more like a media platform where everybody can voice their opinions, WeChat is primarily a social networking tool for friends, although it also serves similar purposes as a media platform.

What is WeChat?

Tencent, which launched WeChat, is one of the largest Internet companies in China and provider of popular instant messaging tools like QQ. WeChat supports text messaging, hold-to-talk and broadcast messaging, among other options. It also allows users to share pictures and status updates. Users can import friends from mobile and QQ contacts.

More people are turning to WeChat to connect with friends. Traditional media have also been quick to incorporate WeChat into their new media strategies as a more direct way to reach audiences. The mobile app also turns individuals into media outlets, allowing them to broadcast to audiences on a subscription basis.

Individuals and organizations can set up "public WeChat accounts" that send messages or newsletters to users who follow, or "subscribe" to these accounts. In August, WeChat released its updated version in which messages from public accounts are grouped together, instead of being displayed independently in the app.

But unlike Weibo, where people can browse through an array of accounts and follow whoever they like, users need to find an account through its name or barcode on WeChat.

Kang Guoping, an independent commentator who works in the IT industry, set up his own "public account" earlier this year. He said it drives him to keep writing every day. His public account has nearly 2,000 subscriptions.

Other IT observers and professionals started much earlier and have much greater influence, gathering tens of thousands of followers, and some have even started generating advertising revenues.

Many have compared Weibo to a big square where everybody can speak, and the one who speaks the loudest gets the most attention, while WeChat is more like a private club or a dinner table where friends can have a more intimate conversation, said Kang.

Declining fortunes

In the fourth quarter of 2012, the level of activity on Sina Weibo declined by nearly 40 percent compared with the second quarter of that year, according to GlobalWebIndex, a London-based market research firm. This decline applies not only to Sina but to microblogging services by other providers like Tencent.

Since August, the authorities have cracked down on "big V's," celebrities on Weibo whose identities have been verified by Sina. Charles Xue, a Chinese-American angel investor known online as Xue Manzi, was detained on August 23 on charges of soliciting prostitutes. Xue, with close to 12 million followers on Weibo, was active on the platform, commenting on hot political and social topics and launching charity campaigns.

In an interview aired on China Central Television (CCTV) in mid-September, a shackled Xue said that he had been blinded by the fame he found on Weibo and had become careless in posting and reposting messages.

The campaign was supposed to be targeting reckless making and spreading of rumors on social media, but the move has been interpreted by many as a way to deter discussion of public affairs.

Although many users feel Weibo has become less active than in the past, Sina announced that by the end of the third quarter, daily active users on Weibo reached over 60 million, an 11.5 percent increase compared with the previous quarter.

Meanwhile, WeChat's popularity, especially among teenagers, is soaring. Active usage of WeChat among teenagers grew by 1,021 percent between the first and third quarters this year, according to GlobalWebIndex.

Influence aside, there's no doubt WeChat has been taking users' attention away from Weibo.

Dodging the restrictions

Broadcasts by public accounts are restricted, although this can be circumvented. Phoenix We Media, a public account on WeChat, says on its introduction that its content is often "restricted" and suggests that users "take caution" when reading. The account sends out "independent, objective and in-depth political information" daily. It's not clear whether the account is related to the Hong Kong-based media group Phoenix.

When the account cannot send its "daily newsletter," it sends each user a message with a keyword. When users reply with the keyword, the account sends the newsletter to users. For instance on November 28, the account sent out a message saying, "Today we are restricted again. Reply with '131128' to receive content." Upon replying, users can get a newsletter with three stories in it.

The three "restricted" stories for the day included a close look at the think tank for Zhongnanhai (location of the Chinese central government), a brief on the sex culture festival in Guangzhou, and a piece on the reform of the way official cars are used.

It appears that chatting content is less strictly monitored than public accounts' broadcasts. The fact that it is much more difficult to censor voice chats may be a reason. But even if WeChat for the moment appears to be less heavily censored, there's no doubt that the content is being monitored. For instance, any mention of "bankcard" in the chat will prompt a reminder to be cautious when transferring money to strangers.

The case that has received the most attention occurred in January this year when it was reported that WeChat was filtering and blocking certain keywords globally. Messages containing the Chinese name of Southern Weekly, a Guangzhou-based newspaper known for its liberal stand, could not be sent. A warning would pop up reminding users that the message contains restricted words.

Tencent later explained to its overseas users that the problem was due to a technical glitch.

New threat

On November 18, CCTV aired a program exposing pornographic content on Wechat, a move that reminded people of the fall of Charles Xue and that has been interpreted by many as signaling tighter controls over new popular social media.

User "Laoxu Shiping," an independent commentator, wrote on Weibo that the special CCTV programs show that Wechat would be closely watched in the future. "Articles shared on Moments and by public accounts would especially be getting a lot of attention, and some accounts would surely be revoked. Be safe out there!" he wrote.

Tencent said it was aware of some illegal activities on WeChat and was working to clean up such accounts. It has revoked a number of public accounts in the past.

Ye Du, a Guangzhou-based writer, told Deutsche Welle in November that since the crackdown on Weibo celebrities, some public figures have moved on to WeChat, opening up public accounts and continuing political discussions.

He also said that gras-roots groups on WeChat are more active and perhaps more dangerous in the eyes of the authorities. "Weibo only spreads information, but its power is limited in terms of organizing groups, and WeChat serves that purpose," he was quoted as saying.

It's generally believed that to some extent, Weibo gives Chinese people freedom of speech, while WeChat gives people freedom of association, said Yu Guoming, a professor of journalism and observer of new media at Renmin University of China in Beijing.

But unlike Weibo, which many see as a driving force for political discussions and participation, at the moment the value of WeChat seems more financial than political.

"Weibo is a public space, but WeChat isn't; it's a small circle of close contacts where people can stick together and support each other," said Yu.

"Weibo relies on negative information, hot issues, extreme cases, to get attention, but on WeChat it's different," said Qiu. "I don't want to bring a lot of negative energy or complaints to my circle of friends on WeChat."

Qiu said he posts more relaxed, fun stuff on WeChat and shares his own essays or pictures he took to WeChat groups.

Among the 300 or so WeChat groups joined by Qiu, some are initiated by him. Mostly lawyers, these contacts are grouped according to their field of expertise or specific topics. Qiu is also in a variety of other groups of friends, or people with shared interests.

On Weibo it's easy to engage in wars of words and discussions can easily get out of hand and turn ugly, but WeChat seems less noisy, since most of the contacts are friends or friends of friends, he added. It's also easier to block an unwelcome friend on WeChat than followers on Weibo.

Qiu said he spends much more time on WeChat these days than on Weibo, but will still turn to Weibo when something happens. However, WeChat serves a much more important purpose of consolidating resources. Interacting with each other every day on WeChat groups brings people much closer. Qiu also said he has been using WeChat to build up his own professional and social reputation and in the future would hope to use it for social good.