HOME >> METRO SHANGHAI

Downbeats and upbeats

By Liao Fangzhou Source:Global Times Published: 2013-12-2 19:08:02

Editor's note

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

Before Shanghai opened its port in 1843, the only music that could be heard in the city was played by traditional Chinese musical instruments including the local sizhu groups ("the silk and bamboo" instrumental ensembles).

The music changed that year when the British owned Moutrie shop opened in Nanjing Road selling Western musical instruments and sheet music. It was China's earliest Western music shop and sold pianos, accordions, and harmoniums for churches. (The first Western keyboard instrument to arrive in China came with the legendary Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci who, in 1601, presented a harpsichord or clavichord from Italy to the emperor and taught four eunuchs how to play it.)

By 1894 in Shanghai the Moutrie shop was advertising in the Shen Bao newspaper with an even wider range of instruments for sale including woodwind, brass, and percussion instruments. In 1890, a former Moutrie employee Huang Xiangxing opened the first locally made Western musical instrument store and by the 1930s there were 10 music shops in town.

On November 22, 1864 an ensemble was reported to have given a concert of Western music at the St. Joseph's Catholic Church, which had been built in 1860 on Sichuan Road South. It was a feast day and the ensemble accompanied a mass - all the musicians were Chinese and they played French instruments.

The city's first official music ensemble, the Shanghai Public Band, made its debut on January 16, 1879, according to Tang Zhenchang's Shanghai Shi (The History of Shanghai). The band evolved from a group of Filipino musicians who had been hired to play music for an amateur theater show at the Lyceum Theatre in the International Concession.

The first orchestra

The Shanghai Public Band started as a brass band but expanded and became a fully fledged orchestra in 1907. The band's new German conductor, Rudolf Buck, arrived with another six professional musicians from Europe and they were paid by the Shanghai Municipal Council, the governing authority of the International Settlement.

From then on the orchestra gave regular concerts. The earliest programs date from 1913 and show that Buck was the conductor and the orchestra presented, among other symphonic works, violin concertos by Beethoven and Mozart.

In September 1919 the Italian pianist and conductor Mario Paci took the baton from Buck. Eager to boost the standard of the orchestra, Paci went to Europe searching for talent and returned with several new players including the gifted violinist Arrigo Foa who became concertmaster and later the conductor of the orchestra.

In 1922, the band was officially renamed the Shanghai Municipal Council Symphony Orchestra. Its performance season ran from October to May and its repertoire was extensive.

The Russians were a remarkable presence in old Shanghai's music. Not only did they account for more than half of the orchestra players, they also formed the largest percentage of the audiences. According to Professor Yasuko Enomoto, a research fellow into the development of Western music in Shanghai, the municipal orchestral concerts were initially free to all expats residing in the settlements but had to start charging admission because of the huge numbers of Russians who showed up to claim seats.

Enomoto noted that Russians were also the core audience of the outdoor summer concerts. As well as playing in the Municipal Council Building hall, the Lyceum Theatre, and the Ever Shining Circuit Cinema, in 1930 the orchestra began to give regular summer night concerts in Jessfield Park (now Zhongshan Park), Gu's Park (Fuxing Park), and the Public Garden (Huangpu Park).

The orchestra was not the only source of Western music in the city. During the 1930s and 1940s, a stream of acclaimed pianists, violinists, and cellists from Russia and Italy visited Shanghai to perform in the Nanjing Drama Hall (now the Shanghai Concert Hall).

Local participation

Over time Chinese became increasingly appreciative of Western classical music. While in the early stages the audiences for concerts were comprised almost entirely of foreigners, by 1931 about 20 percent of its audience was Chinese and the percentage was rising.

The Chinese didn't just join the expats in listening to Western music, but began playing it as well. There were ensembles like the Zhu family which became popular in the 1930s and 1940s. The oldest son of 14 children, the talented Zhu Yisheng, studied music with two US musicians who were then leading performers at Shanghai's upmarket hotels. The two of them shared a flat on Yanqing Road and Zhu had lessons with them twice a week. It cost him $5 an hour but then he went home and passed on the lessons to his brothers and sisters.

The Zhu children had all attended church schools and churches and were familiar with Western music. The family became proficient and formed a band and every Sunday the living room of the Zhu mansion on 5 Shaoxing Road became a rehearsal room. The Zhu family gave Thanksgiving and Christmas parties which hundreds attended to enjoy the music. The Zhu family band began playing for other families around Shanghai and became extremely popular.

Zhu learned to play from expat musicians but formal Western music education had been available in Shanghai from 1906. The University of Shanghai (now the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology), a Baptist university established by Americans, opened a music department which offered courses teaching students how to play Western musical instruments.

Another prominent music educator in the early days was Zeng Zhiwen, the son of a Shanghai businessman who returned to Shanghai in 1907 from Japan where he had studied Western music. In 1908 Zeng established an orphanage and the following year the orphanage students began to learn how to play a selection of instruments. That June, the orphanage's newly established brass band performed at the memorial service for Zeng's father. By December the orphanage school had a 20-piece orchestra.

The Shanghai Academy of Art, the former Shanghai School of Fine Arts, China's first private art school, established by the artist Liu Haisu in November 1912, also featured a music department.

Major milestone

A major milestone in the development of music in the city happened with the establishment of the first state conservatory, now the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, in November 1927. The conservatory promised to "import world music and reflect on national music, at the same time cultivating an appreciation of beauty and harmony."

The conservatory initially had four departments: composition theory, piano, violin, and vocal. Students came all over the country and Shanghai applicants were given no priority. A few foreign students were accepted - most of these were Russians.

Most of the lecturers on Western music (the school also taught the traditional erhu and pipa) came from Russia, Italy, and Hungary and some were also players with the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra. The Chinese staff had studied at leading conservatories in the US.

Other foreign lecturers joined the school later as it gained in reputation. Boris Zakharoff was a prestigious Russian pianist and when the conservatory's founder Xiao Youmei visited him in 1929 to offer him a position in Shanghai, Zakharoff coolly rejected the offer telling him "Chinese students are toddlers and there is no need to employ someone like me to teach them" - as the noted art critic Fu Lei reported. Xiao, however, persisted and finally won Zakharoff by offering a rather exorbitant salary of 400 silver dollars a month (the same amount the head of the conservatory was paid) to teach just seven students. Other teachers at the school at the time were being paid between 200 and 280 silver dollars a month and had to teach at least 12 students.

Ding Shande was one of the conservatory's earliest students and went on to become a distinguished composer and pianist and the school's deputy head. He was one of the first students to study the piano with Zakharoff and, despite his admiration for Zakharoff's skills and charisma, he often found him intimidating. Ding recalled when he played satisfactorily Zakharoff would pat his shoulders or hug him and call him a good boy but when the music didn't go smoothly he would slap his head and yell "I'll kill you."

But Zakharoff could also be a most generous teacher. Li Cuizhen, who entered the conservatory in the autumn of 1929, was held to be an exceptional interpreter of Beethoven and in just one year Zakharoff pushed her through the grades that would normally take a student six to nine years.

Li shone in the first conservatory student concert on May 26, 1930 at the American Women's Club of Shanghai. The audience was a mixture of Chinese and expats and Li was the soloist in Chopin's Piano Concerto No.1. After graduation she went on to study at the Royal Academy of Music in Britain and came back to Shanghai to teach piano in her alma mater.

Over time, the initially reluctant Zakharoff found himself impressed by the enthusiasm the Chinese students showed and, according to a letter, quoted in the works of Nie Er (the composer of the national anthem of the People's Republic of China), he wrote: "I'd like to happily admit that my estimation was wrong. I am filled with joy at continuing my teaching career here as the Chinese students give me great pleasure." He taught piano in Shanghai until his death in 1943.

A new approach

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, there was less concentration on Western music as such and classical musicians turned their attention more to revolutionary, pro-Communist Party of China music from the 1950s.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), classical Western music was banned and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music suffered more than most schools - staff and students were humiliated and tortured. The brilliant pianist Li Cuizhen (then a lecturer) was one of the faculty members who committed suicide during the upheavals of the period. In 1970 the college had 250 music students but the school also had 30 solitary confinement booths.

After 1978, classical Western music enjoyed a revival. From 1980 scores of Shanghai musicians began winning awards, competitions and critical acclaim around the world. In 1987, Shanghai launched a 10-grade piano playing assessment system which stimulated a craze for learning the piano. Sheng Yiqi, an assistant professor with the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, said the system initially saw just 10 students taking part but now involved 30,000 each year.

Compiled by Liao Fangzhou

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

The luster on an old French horn glows in the light. Photo: CFP

Before Shanghai opened its port in 1843, the only music that could be heard in the city was played by traditional Chinese musical instruments including the local sizhu groups ("the silk and bamboo" instrumental ensembles).

The music changed that year when the British owned Moutrie shop opened in Nanjing Road selling Western musical instruments and sheet music. It was China's earliest Western music shop and sold pianos, accordions, and harmoniums for churches. (The first Western keyboard instrument to arrive in China came with the legendary Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci who, in 1601, presented a harpsichord or clavichord from Italy to the emperor and taught four eunuchs how to play it.)

By 1894 in Shanghai the Moutrie shop was advertising in the Shen Bao newspaper with an even wider range of instruments for sale including woodwind, brass, and percussion instruments. In 1890, a former Moutrie employee Huang Xiangxing opened the first locally made Western musical instrument store and by the 1930s there were 10 music shops in town.

On November 22, 1864 an ensemble was reported to have given a concert of Western music at the St. Joseph's Catholic Church, which had been built in 1860 on Sichuan Road South. It was a feast day and the ensemble accompanied a mass - all the musicians were Chinese and they played French instruments.

The city's first official music ensemble, the Shanghai Public Band, made its debut on January 16, 1879, according to Tang Zhenchang's Shanghai Shi (The History of Shanghai). The band evolved from a group of Filipino musicians who had been hired to play music for an amateur theater show at the Lyceum Theatre in the International Concession.

A white and black keyboard on an antique forte piano now preserved by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra Photo: CFP

The first orchestra

The Shanghai Public Band started as a brass band but expanded and became a fully fledged orchestra in 1907. The band's new German conductor, Rudolf Buck, arrived with another six professional musicians from Europe and they were paid by the Shanghai Municipal Council, the governing authority of the International Settlement.

From then on the orchestra gave regular concerts. The earliest programs date from 1913 and show that Buck was the conductor and the orchestra presented, among other symphonic works, violin concertos by Beethoven and Mozart.

In September 1919 the Italian pianist and conductor Mario Paci took the baton from Buck. Eager to boost the standard of the orchestra, Paci went to Europe searching for talent and returned with several new players including the gifted violinist Arrigo Foa who became concertmaster and later the conductor of the orchestra.

In 1922, the band was officially renamed the Shanghai Municipal Council Symphony Orchestra. Its performance season ran from October to May and its repertoire was extensive.

The Russians were a remarkable presence in old Shanghai's music. Not only did they account for more than half of the orchestra players, they also formed the largest percentage of the audiences. According to Professor Yasuko Enomoto, a research fellow into the development of Western music in Shanghai, the municipal orchestral concerts were initially free to all expats residing in the settlements but had to start charging admission because of the huge numbers of Russians who showed up to claim seats.

Enomoto noted that Russians were also the core audience of the outdoor summer concerts. As well as playing in the Municipal Council Building hall, the Lyceum Theatre, and the Ever Shining Circuit Cinema, in 1930 the orchestra began to give regular summer night concerts in Jessfield Park (now Zhongshan Park), Gu's Park (Fuxing Park), and the Public Garden (Huangpu Park).

The orchestra was not the only source of Western music in the city. During the 1930s and 1940s, a stream of acclaimed pianists, violinists, and cellists from Russia and Italy visited Shanghai to perform in the Nanjing Drama Hall (now the Shanghai Concert Hall).

Local participation

Over time Chinese became increasingly appreciative of Western classical music. While in the early stages the audiences for concerts were comprised almost entirely of foreigners, by 1931 about 20 percent of its audience was Chinese and the percentage was rising.

The Chinese didn't just join the expats in listening to Western music, but began playing it as well. There were ensembles like the Zhu family which became popular in the 1930s and 1940s. The oldest son of 14 children, the talented Zhu Yisheng, studied music with two US musicians who were then leading performers at Shanghai's upmarket hotels. The two of them shared a flat on Yanqing Road and Zhu had lessons with them twice a week. It cost him $5 an hour but then he went home and passed on the lessons to his brothers and sisters.

The Zhu children had all attended church schools and churches and were familiar with Western music. The family became proficient and formed a band and every Sunday the living room of the Zhu mansion on 5 Shaoxing Road became a rehearsal room. The Zhu family gave Thanksgiving and Christmas parties which hundreds attended to enjoy the music. The Zhu family band began playing for other families around Shanghai and became extremely popular.

Zhu learned to play from expat musicians but formal Western music education had been available in Shanghai from 1906. The University of Shanghai (now the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology), a Baptist university established by Americans, opened a music department which offered courses teaching students how to play Western musical instruments.

Another prominent music educator in the early days was Zeng Zhiwen, the son of a Shanghai businessman who returned to Shanghai in 1907 from Japan where he had studied Western music. In 1908 Zeng established an orphanage and the following year the orphanage students began to learn how to play a selection of instruments. That June, the orphanage's newly established brass band performed at the memorial service for Zeng's father. By December the orphanage school had a 20-piece orchestra.

The Shanghai Academy of Art, the former Shanghai School of Fine Arts, China's first private art school, established by the artist Liu Haisu in November 1912, also featured a music department.

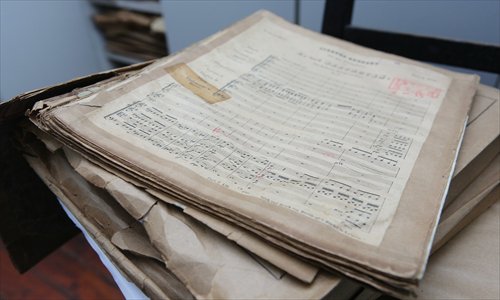

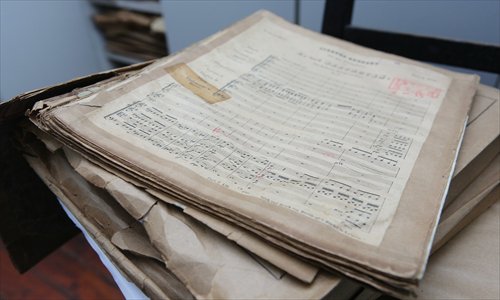

An old orchestral score belonging to the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra Photo: CFP

Major milestone

A major milestone in the development of music in the city happened with the establishment of the first state conservatory, now the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, in November 1927. The conservatory promised to "import world music and reflect on national music, at the same time cultivating an appreciation of beauty and harmony."

The conservatory initially had four departments: composition theory, piano, violin, and vocal. Students came all over the country and Shanghai applicants were given no priority. A few foreign students were accepted - most of these were Russians.

Most of the lecturers on Western music (the school also taught the traditional erhu and pipa) came from Russia, Italy, and Hungary and some were also players with the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra. The Chinese staff had studied at leading conservatories in the US.

Other foreign lecturers joined the school later as it gained in reputation. Boris Zakharoff was a prestigious Russian pianist and when the conservatory's founder Xiao Youmei visited him in 1929 to offer him a position in Shanghai, Zakharoff coolly rejected the offer telling him "Chinese students are toddlers and there is no need to employ someone like me to teach them" - as the noted art critic Fu Lei reported. Xiao, however, persisted and finally won Zakharoff by offering a rather exorbitant salary of 400 silver dollars a month (the same amount the head of the conservatory was paid) to teach just seven students. Other teachers at the school at the time were being paid between 200 and 280 silver dollars a month and had to teach at least 12 students.

Ding Shande was one of the conservatory's earliest students and went on to become a distinguished composer and pianist and the school's deputy head. He was one of the first students to study the piano with Zakharoff and, despite his admiration for Zakharoff's skills and charisma, he often found him intimidating. Ding recalled when he played satisfactorily Zakharoff would pat his shoulders or hug him and call him a good boy but when the music didn't go smoothly he would slap his head and yell "I'll kill you."

But Zakharoff could also be a most generous teacher. Li Cuizhen, who entered the conservatory in the autumn of 1929, was held to be an exceptional interpreter of Beethoven and in just one year Zakharoff pushed her through the grades that would normally take a student six to nine years.

Li shone in the first conservatory student concert on May 26, 1930 at the American Women's Club of Shanghai. The audience was a mixture of Chinese and expats and Li was the soloist in Chopin's Piano Concerto No.1. After graduation she went on to study at the Royal Academy of Music in Britain and came back to Shanghai to teach piano in her alma mater.

Over time, the initially reluctant Zakharoff found himself impressed by the enthusiasm the Chinese students showed and, according to a letter, quoted in the works of Nie Er (the composer of the national anthem of the People's Republic of China), he wrote: "I'd like to happily admit that my estimation was wrong. I am filled with joy at continuing my teaching career here as the Chinese students give me great pleasure." He taught piano in Shanghai until his death in 1943.

A new approach

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, there was less concentration on Western music as such and classical musicians turned their attention more to revolutionary, pro-Communist Party of China music from the 1950s.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), classical Western music was banned and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music suffered more than most schools - staff and students were humiliated and tortured. The brilliant pianist Li Cuizhen (then a lecturer) was one of the faculty members who committed suicide during the upheavals of the period. In 1970 the college had 250 music students but the school also had 30 solitary confinement booths.

After 1978, classical Western music enjoyed a revival. From 1980 scores of Shanghai musicians began winning awards, competitions and critical acclaim around the world. In 1987, Shanghai launched a 10-grade piano playing assessment system which stimulated a craze for learning the piano. Sheng Yiqi, an assistant professor with the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, said the system initially saw just 10 students taking part but now involved 30,000 each year.

Compiled by Liao Fangzhou

Posted in: Metro Shanghai, Meeting up with old Shanghai