HOME >> METRO SHANGHAI

Digging up the past

By Zhang Yu Source:Global Times Published: 2013-12-9 18:33:01

Editor's note

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

"Kind friends look down upon my grave and read that far from home, I died young. Take warning and be prepared, for you know not how soon your turn may come."

This was the epitaph of a 19-year-old sailor named Gissing, originally from Mendlesham, Suffolk in Britain, who died in 1863 in Shanghai. He was buried in Pudong Sailors' Cemetery in today's Lujiazui. British historian E. S. Elliston wrote the pamphlet, "Shantung Road Cemetery," 83 years later, recording the history of the foreign cemeteries in Shanghai and the people buried there, and included Gissing's epitaph.

Gissing was just one of thousands of foreigners who were buried in Shanghai. Many who were buried actually hadn't died here. Before the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, a journey from Europe to Shanghai took up to six months. By the time ships arrived in Shanghai, some of the crew or passengers on board would have died. Others would be so ill they would not be able to return.

Humanitarian view

Elliston noted that Westerners in Shanghai saw the necessity of reserving a place as a cemetery for foreigners. In 1844, after a meeting at the British Consulate in Shanghai, a 0.7-hectare block of land was purchased. The British government paid half the cost, while the rest was funded by members of the foreign community. Elliston said it was more from a humanitarian point of view that they financed the cemetery.

This cemetery was sited near the Bund. But it was soon realized that the site was too close to the growing city center and was not suitable for use as a cemetery. In 1846, the land was exchanged for another site, located north and south on today's Jiujiang Road and Hankou Road, and east and west on today's Shandong Road Middle and Shanxi Road South. This would become the Shandong Road Cemetery, the first foreign cemetery in Shanghai. It covered 0.93 hectares.

From 1846 to its closure around 1868, 469 people were buried there. Although British and American graves predominated, nationals of almost every Western nation could be found there. As Shanghai served primarily as a shipping port, the graves mostly belonged to seamen. But after sailors, missionaries filled the next group of professions buried there. After that merchants and traders made up a large percentage of the deceased, followed by other occupations such as policemen, masons, doctors and servants. Many died aged between 20 and 40.

The Shandong Road Cemetery served as the principal burial place for foreigners in Shanghai, until it was nearly full in 1868. Without a fixed income the cemetery had become too heavy a financial burden for its unofficial management committee to run and it stopped accepting bodies.

When Elliston visited the cemetery in the 1940s he said it "recalls Shanghai's very earliest days, with many tombstones still standing … The whole cemetery is safely guarded in the heart of this throbbing city, shaded by weeping willows, ailanthus, and recently planted gingkos." As Shanghai is relatively low-lying, most of the graves were shallow, and covered with bricks, and about a fifth of the bodies were placed in mausoleums above the ground.

In 1855, another cemetery was built in Pudong in today's Lujiazui, the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery. The first recorded internment, according to Elliston, occurred in 1858, and eventually it contained the graves of 1,783 foreign sailors.

Apart from these, the Municipal Council, which had been established in 1854 to govern the International Settlement, appointed a special committee to explore the possibility of purchasing new ground for future use as a cemetery, considering the increasing foreign population in Shanghai and the fact that the Shandong Road Cemetery was rapidly filling up.

In 1863, the settlement purchased a site that faced Avenue Joffre, today's Huaihai Road, which was within the Chinese territory at the time and connected with the International Settlement via Cemetery Road. As people had to pass by the Baxian Bridge (literally the Eight Immortals Bridge) to get to the cemetery, the cemetery was named the Baxian Bridge Cemetery. It covered 3.2 hectares and was nearly filled by the 1940s.

First crematorium

Other cemeteries sprang up in the city, including the Bubbling Well Road Cemetery which was opened in 1880 and was home to over 5,500 foreign graves, according to "Shanghai's Lost Foreigner Cemeteries" by Eric N. Danielson. There was also the Jewish cemetery which had been donated to the Jewish community by David Sassoon in 1879. The Bubbling Well Road Cemetery had Shanghai's first crematorium, which was initially built for foreigners who wanted their ashes to be sent home.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese government dismantled all the tombs in the foreign cemeteries in the city center. It is not clear where they were moved, or how they were exhumed, but one report suggested they were all moved to the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery. As most of these cemeteries were surrounded with trees and greenery many were transformed into parks. The Bubbling Well Road Cemetery became Jing'an Park in 1954 and the Baxian Bridge Cemetery became Huaihai Park in 1958. The Shandong Road Cemetery is today the Huangpu District Stadium and the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery was turned into Pudong Park in 1957, near today's Oriental Pearl Tower.

Although the foreign cemeteries were not open to the Chinese, they offered a stark contrast to traditional Chinese burials. In those days Chinese often buried coffins at random, either out of poverty or because a feng shui grave site was still being searched for. There was also a deep-rooted belief that Chinese people should be buried in their place of birth.

Shanghai's various hometown associations built temporary morgues. The Ningbo Hometown Association, for example, established the Siming Gongsuo which stored the bodies of Ningbo people until they could be sent back home on the biannual funeral boats. Although these morgues were an embodiment of charity and care, they were also often a source of disease.

The Western cemeteries spurred China to modernize its own burial traditions and in 1909, the first Chinese cemetery, the International (Wanguo) Cemetery was opened on Hongqiao Road. The cemetery would become home to thousands of dead Chinese and was famed for its orderly tombstones.

As well as cemeteries, traditional Chinese funeral services saw Western competitors moving in after Shanghai opened its port.

Shanghai's traditional funerals involved hongbaigang, "the red and white bearers" who bore brides' palanquins at weddings and coffins at funerals. Most of them were found around temples, and their services included decorating rooms, usually with white cloths, providing tableware and organizing funerals. Many Chinese funeral directors were located on today's Yongshou Road (Longevity Road).

Elegant and peaceful

In 1926, a businessman from New York opened the first funeral home in Shanghai, calling it the International (Wanguo) Funeral Home. The company rented a Western-style villa on 207 Jiaozhou Road, not far from the Bubbling Well Road Cemetery, as its funeral home. The ground floor hall had a piano and whenever a service for a foreigner was held, a choir would sing appropriate hymns. Wanguo funeral services looked elegant and peaceful beside the muddled and noisy traditional Chinese funeral affairs.

In 1934, the American manager of the funeral home bought out the business and introduced a range of high-end services catering especially for the rich and famous in Shanghai. As well as the usual services like embalming bodies, applying makeup and dressing the deceased, it offered custom-made caskets and urns. Imported hearses were used. And Chinese music was allowed in the funeral home alongside traditional Chinese rituals. The funeral home became so popular among wealthy locals that the chants of Buddhist and Taoist monks, and the sounds of Chinese instruments were heard regularly.

Among the celebrities who had their funerals at the home was the poet Xu Zhimo, who died in an air crash in 1931 at the age of 34. His body was initially kept at the Fuyuan Temple in Jinan, Shandong Province, before his family members and friends, writer Shen Congwen and architect Liang Sichen, brought it to Shanghai. In 1936 the writer Lu Xun had his funeral there.

The most spectacular funeral at Wanguo was probably that of Ruan Lingyu, a beloved Shanghai actress. Ruan committed suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills on March 8, 1935, aged just 24. She was at the peak of her film career, and her death caused a citywide sensation.

Her funeral service in the Wanguo Funeral Home lasted three days. Ruan, lying on a brown velvet divan, was dressed in a honey-colored qipao and wore diamond earrings and a platinum wedding ring. Her eyes were half-closed, as if still wet with tears, and her cheeks pink. The funeral home viewing room was decorated just like her bedroom had been at her home on Xinzha Road: she was surrounded by her furniture, including a vanity table, a stool and sofa. Her face powder and blusher, combs, brushes and face creams sat alongside a portrait of her with her pet dog on the vanity table, with two qipao draped on the sofa, one yellow and one floral print, her favorites.

The hottest movie stars of the day attended her funeral, including Wang Renmei, Lin Chuchu and Liang Saizhen, and her pallbearers included some of the leading film directors like Li Minwei, Fei Mu, Wu Yonggang and Cai Chusheng. After the service, Ruan's casket was taken to a graveyard in Zhabei district.

A spectacular funeral

Up to 300,000 people came to pay respects to her funeral cortege which stretched for more than 5 kilometers. The New York Times described it as "the most spectacular funeral of the century."

Ruan's death triggered a series of suicides around the city, including Xiang Fuzhen, a film researcher, a fan named Xiachen, and Zhang Meiyin, a staff member at Hangzhou's Lianhua Cinema. According to Daniel Choi's biography of the actress, three women killed themselves on the day of Ruan's funeral. Their suicide notes said the same thing - what was the point of living when Ruan was dead?

The Wanguo Funeral Home spawned a number of Chinese funeral homes. Before 1949, at the peak of the private funeral industry here, there were about 30 funeral homes in Shanghai. After the founding of the PRC, the government promoted cremations over burials, and that began the downfall of many funeral homes which made their profits by selling caskets and graves. Most of the remaining private funeral homes were merged into State-owned businesses.

Compiled by Zhang Yu

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

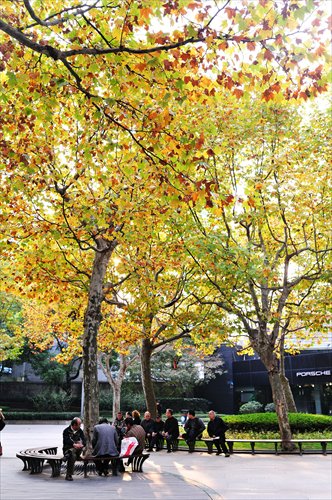

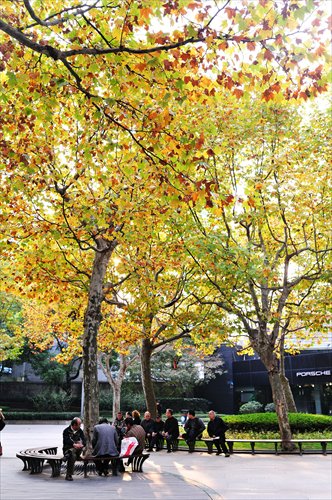

Visitors enjoy a break at Huaihai Park, a former foreign cemetery. Photo:CFP

"Kind friends look down upon my grave and read that far from home, I died young. Take warning and be prepared, for you know not how soon your turn may come."

This was the epitaph of a 19-year-old sailor named Gissing, originally from Mendlesham, Suffolk in Britain, who died in 1863 in Shanghai. He was buried in Pudong Sailors' Cemetery in today's Lujiazui. British historian E. S. Elliston wrote the pamphlet, "Shantung Road Cemetery," 83 years later, recording the history of the foreign cemeteries in Shanghai and the people buried there, and included Gissing's epitaph.

Gissing was just one of thousands of foreigners who were buried in Shanghai. Many who were buried actually hadn't died here. Before the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, a journey from Europe to Shanghai took up to six months. By the time ships arrived in Shanghai, some of the crew or passengers on board would have died. Others would be so ill they would not be able to return.

Humanitarian view

Elliston noted that Westerners in Shanghai saw the necessity of reserving a place as a cemetery for foreigners. In 1844, after a meeting at the British Consulate in Shanghai, a 0.7-hectare block of land was purchased. The British government paid half the cost, while the rest was funded by members of the foreign community. Elliston said it was more from a humanitarian point of view that they financed the cemetery.

This cemetery was sited near the Bund. But it was soon realized that the site was too close to the growing city center and was not suitable for use as a cemetery. In 1846, the land was exchanged for another site, located north and south on today's Jiujiang Road and Hankou Road, and east and west on today's Shandong Road Middle and Shanxi Road South. This would become the Shandong Road Cemetery, the first foreign cemetery in Shanghai. It covered 0.93 hectares.

From 1846 to its closure around 1868, 469 people were buried there. Although British and American graves predominated, nationals of almost every Western nation could be found there. As Shanghai served primarily as a shipping port, the graves mostly belonged to seamen. But after sailors, missionaries filled the next group of professions buried there. After that merchants and traders made up a large percentage of the deceased, followed by other occupations such as policemen, masons, doctors and servants. Many died aged between 20 and 40.

The Shandong Road Cemetery served as the principal burial place for foreigners in Shanghai, until it was nearly full in 1868. Without a fixed income the cemetery had become too heavy a financial burden for its unofficial management committee to run and it stopped accepting bodies.

When Elliston visited the cemetery in the 1940s he said it "recalls Shanghai's very earliest days, with many tombstones still standing … The whole cemetery is safely guarded in the heart of this throbbing city, shaded by weeping willows, ailanthus, and recently planted gingkos." As Shanghai is relatively low-lying, most of the graves were shallow, and covered with bricks, and about a fifth of the bodies were placed in mausoleums above the ground.

In 1855, another cemetery was built in Pudong in today's Lujiazui, the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery. The first recorded internment, according to Elliston, occurred in 1858, and eventually it contained the graves of 1,783 foreign sailors.

Apart from these, the Municipal Council, which had been established in 1854 to govern the International Settlement, appointed a special committee to explore the possibility of purchasing new ground for future use as a cemetery, considering the increasing foreign population in Shanghai and the fact that the Shandong Road Cemetery was rapidly filling up.

In 1863, the settlement purchased a site that faced Avenue Joffre, today's Huaihai Road, which was within the Chinese territory at the time and connected with the International Settlement via Cemetery Road. As people had to pass by the Baxian Bridge (literally the Eight Immortals Bridge) to get to the cemetery, the cemetery was named the Baxian Bridge Cemetery. It covered 3.2 hectares and was nearly filled by the 1940s.

A Shanghai Funeral Museum exhibit illustrates a traditional Chinese funeral with a casket carried by 16 pallbearers. Photo:CFP

First crematorium

Other cemeteries sprang up in the city, including the Bubbling Well Road Cemetery which was opened in 1880 and was home to over 5,500 foreign graves, according to "Shanghai's Lost Foreigner Cemeteries" by Eric N. Danielson. There was also the Jewish cemetery which had been donated to the Jewish community by David Sassoon in 1879. The Bubbling Well Road Cemetery had Shanghai's first crematorium, which was initially built for foreigners who wanted their ashes to be sent home.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese government dismantled all the tombs in the foreign cemeteries in the city center. It is not clear where they were moved, or how they were exhumed, but one report suggested they were all moved to the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery. As most of these cemeteries were surrounded with trees and greenery many were transformed into parks. The Bubbling Well Road Cemetery became Jing'an Park in 1954 and the Baxian Bridge Cemetery became Huaihai Park in 1958. The Shandong Road Cemetery is today the Huangpu District Stadium and the Pudong Sailors' Cemetery was turned into Pudong Park in 1957, near today's Oriental Pearl Tower.

Although the foreign cemeteries were not open to the Chinese, they offered a stark contrast to traditional Chinese burials. In those days Chinese often buried coffins at random, either out of poverty or because a feng shui grave site was still being searched for. There was also a deep-rooted belief that Chinese people should be buried in their place of birth.

Shanghai's various hometown associations built temporary morgues. The Ningbo Hometown Association, for example, established the Siming Gongsuo which stored the bodies of Ningbo people until they could be sent back home on the biannual funeral boats. Although these morgues were an embodiment of charity and care, they were also often a source of disease.

The Western cemeteries spurred China to modernize its own burial traditions and in 1909, the first Chinese cemetery, the International (Wanguo) Cemetery was opened on Hongqiao Road. The cemetery would become home to thousands of dead Chinese and was famed for its orderly tombstones.

As well as cemeteries, traditional Chinese funeral services saw Western competitors moving in after Shanghai opened its port.

Shanghai's traditional funerals involved hongbaigang, "the red and white bearers" who bore brides' palanquins at weddings and coffins at funerals. Most of them were found around temples, and their services included decorating rooms, usually with white cloths, providing tableware and organizing funerals. Many Chinese funeral directors were located on today's Yongshou Road (Longevity Road).

Elegant and peaceful

In 1926, a businessman from New York opened the first funeral home in Shanghai, calling it the International (Wanguo) Funeral Home. The company rented a Western-style villa on 207 Jiaozhou Road, not far from the Bubbling Well Road Cemetery, as its funeral home. The ground floor hall had a piano and whenever a service for a foreigner was held, a choir would sing appropriate hymns. Wanguo funeral services looked elegant and peaceful beside the muddled and noisy traditional Chinese funeral affairs.

In 1934, the American manager of the funeral home bought out the business and introduced a range of high-end services catering especially for the rich and famous in Shanghai. As well as the usual services like embalming bodies, applying makeup and dressing the deceased, it offered custom-made caskets and urns. Imported hearses were used. And Chinese music was allowed in the funeral home alongside traditional Chinese rituals. The funeral home became so popular among wealthy locals that the chants of Buddhist and Taoist monks, and the sounds of Chinese instruments were heard regularly.

Among the celebrities who had their funerals at the home was the poet Xu Zhimo, who died in an air crash in 1931 at the age of 34. His body was initially kept at the Fuyuan Temple in Jinan, Shandong Province, before his family members and friends, writer Shen Congwen and architect Liang Sichen, brought it to Shanghai. In 1936 the writer Lu Xun had his funeral there.

The most spectacular funeral at Wanguo was probably that of Ruan Lingyu, a beloved Shanghai actress. Ruan committed suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills on March 8, 1935, aged just 24. She was at the peak of her film career, and her death caused a citywide sensation.

Her funeral service in the Wanguo Funeral Home lasted three days. Ruan, lying on a brown velvet divan, was dressed in a honey-colored qipao and wore diamond earrings and a platinum wedding ring. Her eyes were half-closed, as if still wet with tears, and her cheeks pink. The funeral home viewing room was decorated just like her bedroom had been at her home on Xinzha Road: she was surrounded by her furniture, including a vanity table, a stool and sofa. Her face powder and blusher, combs, brushes and face creams sat alongside a portrait of her with her pet dog on the vanity table, with two qipao draped on the sofa, one yellow and one floral print, her favorites.

The hottest movie stars of the day attended her funeral, including Wang Renmei, Lin Chuchu and Liang Saizhen, and her pallbearers included some of the leading film directors like Li Minwei, Fei Mu, Wu Yonggang and Cai Chusheng. After the service, Ruan's casket was taken to a graveyard in Zhabei district.

A spectacular funeral

Up to 300,000 people came to pay respects to her funeral cortege which stretched for more than 5 kilometers. The New York Times described it as "the most spectacular funeral of the century."

Ruan's death triggered a series of suicides around the city, including Xiang Fuzhen, a film researcher, a fan named Xiachen, and Zhang Meiyin, a staff member at Hangzhou's Lianhua Cinema. According to Daniel Choi's biography of the actress, three women killed themselves on the day of Ruan's funeral. Their suicide notes said the same thing - what was the point of living when Ruan was dead?

The Wanguo Funeral Home spawned a number of Chinese funeral homes. Before 1949, at the peak of the private funeral industry here, there were about 30 funeral homes in Shanghai. After the founding of the PRC, the government promoted cremations over burials, and that began the downfall of many funeral homes which made their profits by selling caskets and graves. Most of the remaining private funeral homes were merged into State-owned businesses.

Compiled by Zhang Yu

Posted in: Metro Shanghai, Meeting up with old Shanghai