HOME >> METRO SHANGHAI

Hard and soft sells

By Zhou Ping Source:Global Times Published: 2013-12-15 18:08:01

Editor's note

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

Chinese businessmen have probably always known about the power of advertising but methods changed after 1843 when Western styles of advertising arrived in Shanghai and other cities. Chinese businesses quickly adapted many of the new forms and moved far beyond their basic signs over shop doors.

Traditionally small Chinese traders would walk the streets with their wares, shouting out what they had to sell. Shopkeepers displayed signs on the doors or counters with the name of the establishment and their specialized products - "Xiyang (West) Biyan (snuff)" or "Suguang (Suzhou and Guangzhou) Yandai (tobacco pipes)."

When Western merchants arrived in the city, at first they put advertising posters printed abroad on the walls around the town. Characters from fairy tales, American landscapes and American heroes like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln often featured in the illustrations. But these specifically Western-oriented displays had little or no appeal for the Chinese and soon Western businessmen began hiring Chinese artists to design their posters, to make them appeal to the locals.

The influential newspaper Shen Bao was launched in 1872 and this marked the beginning of modern advertising forms in Shanghai. On its first edition the newspaper carried 20 advertisements.

More striking

The black and white advertisements in Shen Bao were initially very basic - just the name of the product or the retailer with the address and the price. But later the advertisements became more striking.

Its January 7 edition in 1932 featured a full-page advertisement for Mazhanshan cigarettes (Ma Zhanshan was a prominent Chinese army general who was opposed to the growing influence of the Japanese forces in China). The front page advertisement displayed the name of the brand in larger type than the newspaper's own title next to pictures of the general and a cigarette pack alongside the price - two tins for one silver dollar - and an exhortation that "patriots choose this cigarette above all others."

Another Shen Bao advertisement promoted Pehchaolin, a leading Shanghai makeup brand. Alongside pictures of Peking Opera stars, readers were assured that the stars of Peking Opera and movies knew the value of Pehchaolin face cream.

In Shen Bao's heyday (by the mid-1930s it was selling 150,000 copies a day), more than 60 percent of its content was advertising, pushing a huge range of goods from cigarette to cosmetics, from wine to shoes.

Its major competitor, Sin Wan Pao was launched by Chinese and Western businessmen in 1893 and carried even more advertising. In 1919, the China Advertising Association was established under the auspices of the International Correspondence School's Shanghai office.

In 1926 the first neon-light advertising sign appeared in the window of the Edward Evans and Sons Ltd bookstore on Nanjing Road East. It looked like a Royal brand typewriter keyboard.

Newspaper and magazine advertising was widespread. By 1923, 150,000 Sin Wan Pao papers were sold every day with up to 70 percent of the content advertising, which was bringing in a million silver dollars annually. The Eastern Miscellany magazine, first published by the Commercial Press in 1904, focused on advertisements for US products. Life Weekly, now Sanlian Life Weekly, sold 150,000 copies daily in 1923, and first only carried advertisements for books but branched out to cover a variety of products by late 1929. Magazines like Happy Family and Young Companion were almost half-advertising, half-articles and pictures.

Calendar girls

In the 1920s and 1930s, another form of advertising took Shanghai by storm - the calendar girls, yuefenpai. Yuefenpai was at first a traditional New Year publication printed and distributed before the Chinese New Year. It featured an illustration alongside a calendar for the coming year. Western merchants began to hire Chinese artists to produce special yuefenpai to attract local customers. Large department stores often gave yuefenpai as New Year gifts to loyal customers.

A typical calendar featured an attractive woman as the main picture with details of the company or firm displayed alongside the months of the coming year. While the most common calendars promoted cigarettes others featured liquor, textiles, cosmetics and pesticides. British American Tobacco and Nanyang Brothers Tobacco were major calendar producers.

The yuefenpai with its accent on beautiful women also reflected the changing fashions of the day and sometimes led to changes in clothing and hairstyles and even attitudes.

In the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company's calendars of the 1910s and 1920s, the models began to show ankles, legs and thighs unlike the older traditional models who were covered from head to toe. The new models did not have bound feet and often wore their hair short - traditionally Chinese women only had short hair if they were becoming nuns or if they were in mourning for their husbands.

The yuefenpai became even more daring from 1925 onwards where some of the models revealed cleavage and sometimes a glimpse of a breast. Traditionally women in China were not allowed to show they had breasts. Loose clothing and tightly wound cloths or undergarments kept women flat-chested until 1927 when the government outlawed breast binding.

One of the stars of the day was Lü Meiyu, a Peking Opera singer who had attracted the artist Xie Zhiguang. Her picture appeared on a yuefenpai promoting "My Dear" or Meili cigarettes produced by the Hwa Ching Tobacco Company. When Xie Zhiguang saw her in a magazine he recreated her as the centerpiece of his calendar and advertising campaign. The "My Dear" cigarettes were first put on the market in March 1925 and all the first batch of the cigarettes was sold out in three days. The cigarette became a top seller of the day and women throughout the country sought to emulate the glamorous model in every way possible.

Lü Meiyu enjoyed the fame but eventually had to take the tobacco company to court, suing it for using her image without permission. It was the first case of its sort in China and the company realized it had to pay her compensation because the brand had become so popular. She eventually got royalties on every tin of "My Dear" cigarettes sold and this earned her 20,000 silver dollars over a three-year period from 1926 to 1928 when up to 40,623 boxes of "My Dear" cigarette were sold.

The yuefenpai featured socialites, movie stars, opera singers and good-looking models and the images also appeared in cigarette cards. Yuefenpai were banned during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) but returned in the late 1970s but have now faded into obscurity.

Live on air

China's first three radio stations were all launched in Shanghai by foreign businessmen. On December 19, 1922, The China Press reported on its front page that Shanghai was to have radio.

On January 23, 1923, Shanghai's first radio station, the Radio Corporation of China, which was also known as the Osborn Radio Station, was opened by the American E. G. Osborn two years after the world's first commercial radio station began broadcasting in the US. Osborn's 50-watt transmitter was set up in the Robert Dollar Building on Guangdong Road. The station's first broadcasts ran between 8 pm and 9 pm and included news reports from Shanghai, China, US and Europe, as well as music - violin and saxophone solos chamber music by the Golden Gate String Quartet and dance music. The 500 Shanghai people who had radios at the time were astonished and soon the new medium became part of the city's life.

Osborn worked with The China Press, which published the station's schedules and provided news and the Osborn Radio Station introduced advertising to support its operation.

On January 26, 1923, Sun Yat-sen's speech in Shanghai calling for a unified China was broadcast and listeners as far away as Tianjin heard this. Sun heaped praise on the radio station in a newspaper article two days later, which boosted the reputation of the infant broadcaster. But despite its reputation three months later the station was shut down with the government saying that Osborn had failed to obtain an import license for the equipment.

In the early days of radio in China, the authorities were suspicious of the new medium and tended to treat it as having military potential rather than just providing entertainment and information.

After Osborn, the Electric Equipment Company launched a radio station on Nanjing Road and started broadcasting on May 30, 1923. The station mainly served as a showroom for the company's products - radio sets - and business boomed as people from Shanghai and the neighboring Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces came to buy radios. But in November 1923, the government banned the importation of radios and in August 1924, the company stopped operation after a large amount of equipment was seized by customs officers.

Another station operated by the Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company opened on May 15, 1924 on Route Ferguson (now Wukang Road). It also broadcast from studios in the newspaper Shen Bao, the Shanghai Evening News, and the Paris Restaurant. It built a network combining the radio station, newspapers and shops but the advertising links were not enough to save this operation. It cost the station more than 20,000 silver dollars a year to operate and the financial burden caused it to close in October 1929.

Spurred by the foreigners' radio stations, the Sun Sun Company on Nanjing Road launched its own Chinese radio station. It started broadcasting on March 18, 1927. For six hours a day it aired news, current affairs, Chinese music and excerpts from Cantonese and Kunqu operas. Though the station closed down in October 1929 after just two and a half years, it was a milestone in the broadcasting history of Shanghai. By 1937, Shanghai had 54 radio stations, a lot more than the 24 radio stations then on air in New York.

Compiled by Zhou Ping

From a fishing village with a population of just 200,000 in 1843, Shanghai has developed into a huge modern city where more than 23 million people live. From the time Shanghai was forced to open up as a port in 1843, the city has witnessed remarkable change and progress. This year marks the 170th anniversary of Shanghai's opening-up and in this special series of reports, the Global Times will highlight some of the crucial moments, recall some choice memories of olden days and uncover some of the secrets of the city. Don't miss these exciting insights into the metropolis.

Neon signs on Nanjing Road East bring color and fun to the city. Photo: CFP

Chinese businessmen have probably always known about the power of advertising but methods changed after 1843 when Western styles of advertising arrived in Shanghai and other cities. Chinese businesses quickly adapted many of the new forms and moved far beyond their basic signs over shop doors.

Traditionally small Chinese traders would walk the streets with their wares, shouting out what they had to sell. Shopkeepers displayed signs on the doors or counters with the name of the establishment and their specialized products - "Xiyang (West) Biyan (snuff)" or "Suguang (Suzhou and Guangzhou) Yandai (tobacco pipes)."

When Western merchants arrived in the city, at first they put advertising posters printed abroad on the walls around the town. Characters from fairy tales, American landscapes and American heroes like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln often featured in the illustrations. But these specifically Western-oriented displays had little or no appeal for the Chinese and soon Western businessmen began hiring Chinese artists to design their posters, to make them appeal to the locals.

The influential newspaper Shen Bao was launched in 1872 and this marked the beginning of modern advertising forms in Shanghai. On its first edition the newspaper carried 20 advertisements.

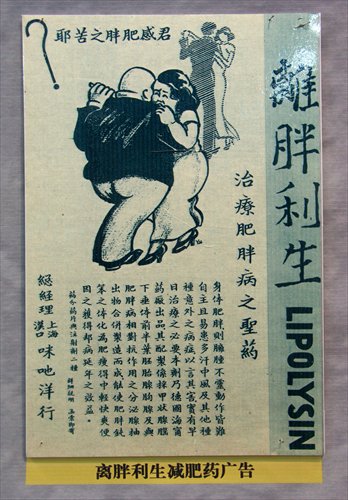

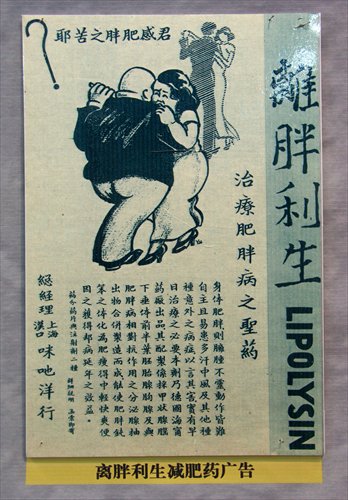

An advertisement for fat-destroying diet pills Photo: CFP

She looks happy and daring as she promotes Three Cats cigarettes. Photo: CFP

More striking

The black and white advertisements in Shen Bao were initially very basic - just the name of the product or the retailer with the address and the price. But later the advertisements became more striking.

Its January 7 edition in 1932 featured a full-page advertisement for Mazhanshan cigarettes (Ma Zhanshan was a prominent Chinese army general who was opposed to the growing influence of the Japanese forces in China). The front page advertisement displayed the name of the brand in larger type than the newspaper's own title next to pictures of the general and a cigarette pack alongside the price - two tins for one silver dollar - and an exhortation that "patriots choose this cigarette above all others."

Another Shen Bao advertisement promoted Pehchaolin, a leading Shanghai makeup brand. Alongside pictures of Peking Opera stars, readers were assured that the stars of Peking Opera and movies knew the value of Pehchaolin face cream.

In Shen Bao's heyday (by the mid-1930s it was selling 150,000 copies a day), more than 60 percent of its content was advertising, pushing a huge range of goods from cigarette to cosmetics, from wine to shoes.

Its major competitor, Sin Wan Pao was launched by Chinese and Western businessmen in 1893 and carried even more advertising. In 1919, the China Advertising Association was established under the auspices of the International Correspondence School's Shanghai office.

In 1926 the first neon-light advertising sign appeared in the window of the Edward Evans and Sons Ltd bookstore on Nanjing Road East. It looked like a Royal brand typewriter keyboard.

Newspaper and magazine advertising was widespread. By 1923, 150,000 Sin Wan Pao papers were sold every day with up to 70 percent of the content advertising, which was bringing in a million silver dollars annually. The Eastern Miscellany magazine, first published by the Commercial Press in 1904, focused on advertisements for US products. Life Weekly, now Sanlian Life Weekly, sold 150,000 copies daily in 1923, and first only carried advertisements for books but branched out to cover a variety of products by late 1929. Magazines like Happy Family and Young Companion were almost half-advertising, half-articles and pictures.

A classical look for the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company Photo: CFP

Lü Meiyu was the face of "My Dear" cigarettes and this eventually earned her fame and fortune. Photo: CFP

Calendar girls

In the 1920s and 1930s, another form of advertising took Shanghai by storm - the calendar girls, yuefenpai. Yuefenpai was at first a traditional New Year publication printed and distributed before the Chinese New Year. It featured an illustration alongside a calendar for the coming year. Western merchants began to hire Chinese artists to produce special yuefenpai to attract local customers. Large department stores often gave yuefenpai as New Year gifts to loyal customers.

A typical calendar featured an attractive woman as the main picture with details of the company or firm displayed alongside the months of the coming year. While the most common calendars promoted cigarettes others featured liquor, textiles, cosmetics and pesticides. British American Tobacco and Nanyang Brothers Tobacco were major calendar producers.

The yuefenpai with its accent on beautiful women also reflected the changing fashions of the day and sometimes led to changes in clothing and hairstyles and even attitudes.

In the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company's calendars of the 1910s and 1920s, the models began to show ankles, legs and thighs unlike the older traditional models who were covered from head to toe. The new models did not have bound feet and often wore their hair short - traditionally Chinese women only had short hair if they were becoming nuns or if they were in mourning for their husbands.

The yuefenpai became even more daring from 1925 onwards where some of the models revealed cleavage and sometimes a glimpse of a breast. Traditionally women in China were not allowed to show they had breasts. Loose clothing and tightly wound cloths or undergarments kept women flat-chested until 1927 when the government outlawed breast binding.

One of the stars of the day was Lü Meiyu, a Peking Opera singer who had attracted the artist Xie Zhiguang. Her picture appeared on a yuefenpai promoting "My Dear" or Meili cigarettes produced by the Hwa Ching Tobacco Company. When Xie Zhiguang saw her in a magazine he recreated her as the centerpiece of his calendar and advertising campaign. The "My Dear" cigarettes were first put on the market in March 1925 and all the first batch of the cigarettes was sold out in three days. The cigarette became a top seller of the day and women throughout the country sought to emulate the glamorous model in every way possible.

Lü Meiyu enjoyed the fame but eventually had to take the tobacco company to court, suing it for using her image without permission. It was the first case of its sort in China and the company realized it had to pay her compensation because the brand had become so popular. She eventually got royalties on every tin of "My Dear" cigarettes sold and this earned her 20,000 silver dollars over a three-year period from 1926 to 1928 when up to 40,623 boxes of "My Dear" cigarette were sold.

The yuefenpai featured socialites, movie stars, opera singers and good-looking models and the images also appeared in cigarette cards. Yuefenpai were banned during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) but returned in the late 1970s but have now faded into obscurity.

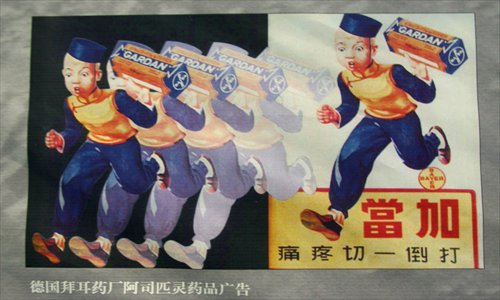

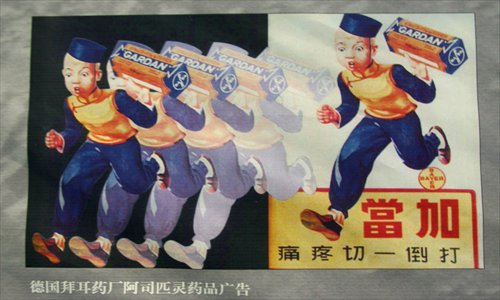

Bayer's Gardan painkillers promise to "kill all pains." Photo: CFP

Live on air

China's first three radio stations were all launched in Shanghai by foreign businessmen. On December 19, 1922, The China Press reported on its front page that Shanghai was to have radio.

On January 23, 1923, Shanghai's first radio station, the Radio Corporation of China, which was also known as the Osborn Radio Station, was opened by the American E. G. Osborn two years after the world's first commercial radio station began broadcasting in the US. Osborn's 50-watt transmitter was set up in the Robert Dollar Building on Guangdong Road. The station's first broadcasts ran between 8 pm and 9 pm and included news reports from Shanghai, China, US and Europe, as well as music - violin and saxophone solos chamber music by the Golden Gate String Quartet and dance music. The 500 Shanghai people who had radios at the time were astonished and soon the new medium became part of the city's life.

Osborn worked with The China Press, which published the station's schedules and provided news and the Osborn Radio Station introduced advertising to support its operation.

On January 26, 1923, Sun Yat-sen's speech in Shanghai calling for a unified China was broadcast and listeners as far away as Tianjin heard this. Sun heaped praise on the radio station in a newspaper article two days later, which boosted the reputation of the infant broadcaster. But despite its reputation three months later the station was shut down with the government saying that Osborn had failed to obtain an import license for the equipment.

In the early days of radio in China, the authorities were suspicious of the new medium and tended to treat it as having military potential rather than just providing entertainment and information.

After Osborn, the Electric Equipment Company launched a radio station on Nanjing Road and started broadcasting on May 30, 1923. The station mainly served as a showroom for the company's products - radio sets - and business boomed as people from Shanghai and the neighboring Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces came to buy radios. But in November 1923, the government banned the importation of radios and in August 1924, the company stopped operation after a large amount of equipment was seized by customs officers.

Another station operated by the Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company opened on May 15, 1924 on Route Ferguson (now Wukang Road). It also broadcast from studios in the newspaper Shen Bao, the Shanghai Evening News, and the Paris Restaurant. It built a network combining the radio station, newspapers and shops but the advertising links were not enough to save this operation. It cost the station more than 20,000 silver dollars a year to operate and the financial burden caused it to close in October 1929.

Spurred by the foreigners' radio stations, the Sun Sun Company on Nanjing Road launched its own Chinese radio station. It started broadcasting on March 18, 1927. For six hours a day it aired news, current affairs, Chinese music and excerpts from Cantonese and Kunqu operas. Though the station closed down in October 1929 after just two and a half years, it was a milestone in the broadcasting history of Shanghai. By 1937, Shanghai had 54 radio stations, a lot more than the 24 radio stations then on air in New York.

Compiled by Zhou Ping

Posted in: Metro Shanghai, Meeting up with old Shanghai