Chinese readers digest the ideas of Hannah Arendt

The seemingly sudden popularity of German-American political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906-75) in China is something more than blind adulation for a difficult-to-pronounce foreign name. Many in Shanghai first encountered the name from the eponymous film screened at the 16th Shanghai International Film Festival last June. Eight months later, Arendt's allure has stayed. She kept pushing us to think.

The latest Chinese translation of her last (and unfinished) work, Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy, attracted "a larger than imagined number of readers," according to a staffer at Shanghai Jifeng Bookstore, to attend a lecture explaining Arendt's theories given by two professors of philosophy from top universities in Shanghai on Sunday afternoon.

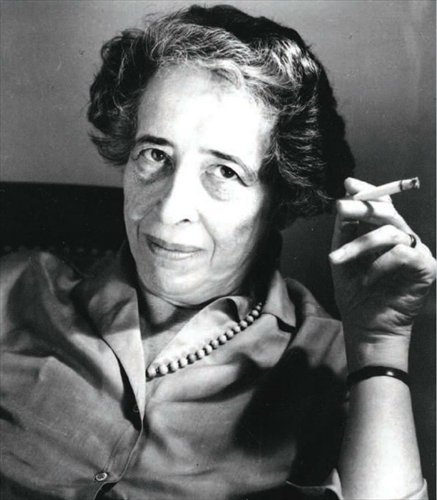

Hannah Arendt

A series of books written by Hannah Arendt Photos: Global Times

The book, though esoteric, will undoubtedly attract Chinese readers interested in the problems that Arendt addresses, such as the relationship between the individual and the state, the "banality of evil," the moral responsibility of a citizen to think and act, the nature of totalitarianism, and how to avoid a tragic future by learning bloody lessons from the past.

"To trace the origins of totalitarianism was one of Hannah Arendt's major contributions. According to Aristotle, there are two types of government, good government and bad government. If a government is for the common good, then it is a good government, and vice versa. But totalitarianism was something totally new. It proclaimed itself to be the agent of history and destroyed individuality, legally, morally, entirely," Wang Yanli, an associate professor of philosophy at East China Normal University and a translator of two of Arendt's books, said.

A victim of Nazi Germany, in 1961 Arendt went to Jerusalem as a special reporter for The New Yorker to witness the trial of Adolf Eichmann, "the last major living Nazi." In the resulting article, Arendt used "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann, who occurred to her to be "terribly and terrifyingly normal," which ignited fierce debate in the West.

A series of books written by Hannah Arendt Photos: Global Times

A series of books written by Hannah Arendt Photos: Global Times

"It seems to be all too easy to understand today," Wang said. Just recall the brutal crimes during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), when everyone was forced to persecute everyone, or the increasingly common news reports nowadays of extreme acts of violence committed by common people, from well-educated college students to a naïve 10-year-old girl.

According to Arendt, Eichmann was certainly not stupid, nor a bureaucratic machine who followed every order, but a man who could not really think beyond Nazi ideology. And to think and reason reasonably was central to the theories of Kant, which Arendt found useful.

"Maybe it's because they both came from Königsberg, Arendt had an exceptional respect for Kant," Hong Tao, a professor who specializes in political philosophy at Fudan University, said. "All philosophers despise politics, with the rare exception of Kant."

"When I was a student I had read this book," Hong said. "I was trying to understand Kant through the teachings of Arendt. But then I found what Arendt wrote was not an interpretation of Kant, but a new theory of her own," which, the two professors themselves humbly admitted that they could not fully understand, either.

This was partly due to the fact that the book was an unfinished third volume of Arendt's posthumously published The Life of the Mind. Many of Arendt's ideas remain unknown, and most questions raised by the audience didn't receive clear, direct answers from the two professors. But instead of taking the solutions of others, it might be better for us to think for ourselves.