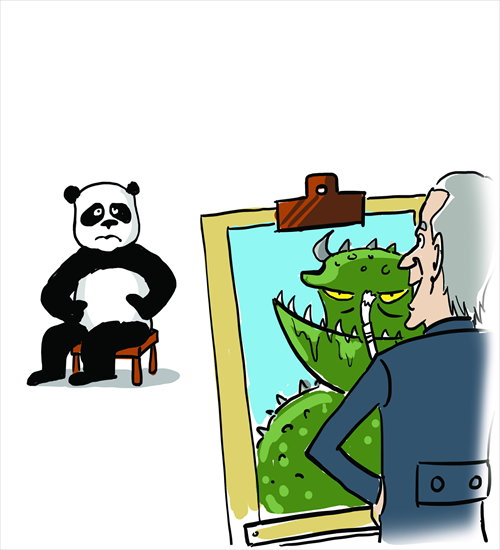

Analysts reckless in claiming similarities to WWI scenario

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

With WWI starting 100 years ago, this year countless articles state that the present competition between the US and China could repeat the conflict that shook the world and killed over 16 million people in Europe.

At that time, the competition between Germany and Britain seemed so stark that conflict seemed inevitable. By extension, some scholars choose to view the rise of China as inevitably prone to conflict as it will challenge the current primary power: the US.

My argument is that such a situation is highly unlikely; that there was nothing inevitable about WWI and there is no inevitability now.

While it is true that the rise of China in terms of its military power and political influence will take up more strategic space in Asia, it is unlikely that China will engage in conflict with the US. Neither is it likely that the US will repeat the disastrous consequences of 1914.

If one dwells into history, the stark and visible example of such a situation arose during the Cuban missile crisis in the 1960s.

Despite being threatened by Soviet missiles 90 miles away in Cuba, then US president John Kennedy chose to negotiate with then Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev rather than engage in war, and this was despite the fact that on October 27, 1962, the Soviets brought down a US U-2 spy plane flying over Cuba, in the process killing the pilot.

That day was the pinnacle of US-USSR tensions and a nuclear war verging on a nuclear winter was most likely, and yet peaceful negotiations held the day.

Unlike 1914, or 1962, when it took nearly 12 hours for a diplomatic cable to travel from Washington to Moscow, the world of 2014 is far more interconnected, with faster channels of communication, deeper societal engagements, multinational businesses and fast civilian modes of travel.

Dozens of flights connect China with the US, dialogues between government officials are held on a regular basis, and regional institutional structures like the East Asia Summit and ASEAN bring them together.

The two countries have the largest trade flows between them, and China holds more US treasury bonds than any other country.

One could still argue that the differences between China and Japan over the disputed islands in the East China Sea, the South China Sea island disputes, and the Taiwan issue may lead to war between China and the US.

This, it is argued, is vindicated by growing Chinese nationalism, which calls for a more assertive Chinese foreign policy.

All true, but a realistic look at East Asia reflects a deeper desire for peaceful development of lifestyles and better material prosperity.

Hence, the issues that hold much more sway in Asia are connected to better living standards, rather than a war over strategic influence in the high seas that will prove destructive.

Given that scenario, a 1914 situation will not be repeated. The most significant reason for this is the change in the structure of international politics.

1914 was dominated by European countries that colonized the world and grabbed land, and no one could stop them from doing so, as there were no international institutions of repute that could caution strategic restraint. Concepts like sovereignty and territorial integrity had not reached maturity at that time.

The world in 2014 is different. China and the US are not colonizers; neither is it likely that Asian powers like China and India will escalate their tensions to the level of a hot war.

While I agree that the competitive edge between the US and China for greater influence in Asia will continue, that the border tensions between China and India will affect their smooth relationship, or that China and Japan will bicker, for strategic analysts especially from the West to suggest that 2014 may repeat 1914 in Asia is not only irresponsible but highly dangerous.

The author is a research fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi and former senior fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, Washington. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Related article: Pre-1914 comparison shows suspicion of rising China