HOME >> OP-ED

Art of war drives strategy in House of Cards

By Rong Xiaoqing Source:Global Times Published: 2014-2-27 19:58:03

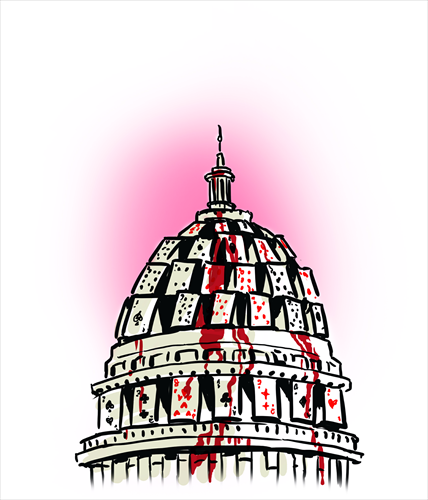

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Suddenly, everybody seems to be talking about House of Cards. My friends in the US compete with one another in a nonstop race to get through the second season of the Netflix political thriller. My friends in China keep updating their progress on their WeChat accounts.US President Barack Obama warned his followers on Twitter not to reveal the plot. And some high-ranking officials in China are said to be feverish fans.

Some of the frenzy is due to Netflix's smart marketing gimmick. This series, like the first, is available all at once, so that if you want to binge-watch all night long and finish the whole thing at 6 am, you can.

It creates a level of excitement that just doesn't exist when a series is dribbled out over 12 weeks in the traditional way. Add in the decision to release simultaneously in China on sohu.com, and a plot line that includes many Sino-US issues, and you have a recipe for a success far beyond US shores.

But you also have to give it to Frank Underwood, played brilliantly by Kevin Spacey, the shrewd politician who is the main character in House of Cards.

It is, of course, still fiction. In the real world, it's unlikely that a congressman could literally get away with murder, manipulate everyone who comes into contact with him, and still manage to rise to be vice president. Even Obama joked: "This guy's getting a lot of stuff done. I wish things were that ruthlessly efficient."

This might be an especially important point to bear in mind for the audience in China, given the tendency of many to confuse fictional depictions with real life in the US, and the fact that many of them take the show as US politics 101.

But even without the Chinese political elements in this season, the show would still have struck a chord in China.

It is basically a White House-Congress version of The Art of War, an ancient Chinese book of military tactics that is believed to have been written by philosopher Sun Tzu.

Look at the following lines:

Underwood: "After all, we are nothing more or less than what we choose to reveal."

Sun Tzu: "All warfare is based on deception."

Underwood: "For those of us climbing to the top of the food chain, there can be no mercy. There is but one rule: Hunt or be hunted."

Sun Tzu: "Thus the expert in battle moves the enemy, and is not moved by him."

Put these together and it feels like the fictional modern US politician and the ancient Chinese philosopher are having a conversation about strategy. And you don't have to understand fundraising, mid-term elections, super political action committees and filibusters to admire these tactics.

Elected or not, people who have the power can easily be intoxicated, addicted and drowned by it. With or without general elections, all kinds of vices can grow in the longing to obtain, maintain and augment power.

To be sure, there are moments in House of Cards when voters matter - when the president's approval rating is plunging, for example. But even that seems to be a demonstration of how public opinions can be used and manipulated by strategists.

China and the US may have different rules in the game of politics. But sometimes the rules are not as important as the players - especially when they are also referees who can make, interpret, and alter the rules. As Underwood put it: "Of all the things I place in high regard, rules are not one of them."

China and the US may each have their own ways to curb the beast of power. But the common enemy they both face is human nature and the ambitions that it nurtures, ambitions that can lead to corruption on a vast scale unless they are addressed.

That may be the reason that cracking down on corruption is a hard job in both China and the US. And it is also the reason that the public in both countries tends to embrace any attempts to do so.

The author is a New York-based journalist. rong_xiaoqing@hotmail.com

Posted in: Viewpoint, Rong Xiaoqing