Searching for the relevant organs

A doctor shows a model of a human heart. About 300,000 people join the transplant waiting list in China annually, but less than 1 percent actually receive a transplant. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Agreeing to donate her daughter's organs was one of the hardest decisions Xu Caiyun has ever made. Xu, 52, burst into tears when the idea was first raised by daughter Jin Yu after she recovered from a coma at Spring Festival earlier this year.

"She knew at the time that she was nearing the end of her life, so she talked to me about donating her organs," Xu recalled. "It was too hard for me. I cried many times over this issue after she told me, but my daughter was so kind and kept talking to me about it for a month. Eventually, I agreed."

Jin, 22, died on March 8 of kidney failure. She had been on the transplant waiting list for almost two years. After her death, Jin's liver and corneas were transplanted to three recipients.

"We searched and waited desperately [for a donated kidney], but all we were left with was pain and agony," said Xu. "My daughter said all of us are reduced to ash in the end, so why not leave our valuable gifts to others? They are of no use in the afterlife."

Around 300,000 people suffer organ failure and join the transplant waiting list in China annually, but the reality is less than 1 percent will actually receive a transplant.

The current national donation system was only launched in 2010, with most organs for transplants before then being sourced from either recipients' relatives or executed prisoners. By mid-2014, all hospitals licensed for organ transplants will be required to stop using organs from executed prisoners and only use those voluntarily donated.

The new system has done little to ease China's shortage of organ donors. According to 2012 figures from the Red Cross Society of China (RCSC), the ratio of patients in need of a transplant to organ donors is as high as 150:1 in China, compared to 5:1 in the US and 3:1 in the UK.

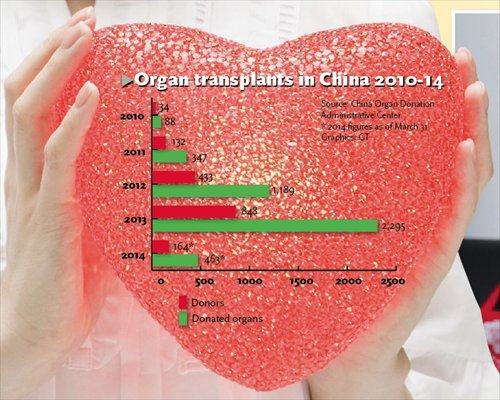

Gao Xinpu, media officer with the China Organ Donation Administrative Center (CODAC), said since 2010 more than 1,600 people have donated over 4,300 organs after death.

An elderly couple fill out application forms to register as organ donors in Kunming, Yunnan Province. Photo: CFP

Leaving a lifesaving legacy

Xu honored Jin's request to donate her liver despite initially believing it would be unsuitable. Jin's condition had deteriorated so rapidly that she weighed just 30 kilograms at her death.

"When [Jin] told me that her liver was healthy, I had doubts. But after she died, doctors told me they couldn't believe how plump and healthy it was," said Xu. "At that moment, I understood why my daughter had refused medication for the past year - she knew it would harm her liver."

Xu arranged for Jin's organs to be donated at Peking University People's Hospital, where she had been hospitalized prior to her death.

Kou Yuqing, 78, registered as an organ donor in February. The widow decided four years ago that she wanted to donate all of her organs, but it wasn't until this year that she registered as a donor because she didn't know where to start.

"My relatives and friends told me I could register in Beijing, but none of them knew where exactly. I eventually consulted my doctor at the Dongzhimen Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital," said Kou.

Even though she doesn't have much to pass on financially after she dies, Kou is determined to make a difference by possibly saving a stranger's life with her organs.

"When I reflected on my life recently, I realized I hadn't done anything useful for society. I hope that my organs can be of benefit to someone," said Kou.

The liver and kidney are the most commonly donated organs in China, with both also in highest demand on the transplant waiting list.

Doctors bow to a deceased male organ donor before an operation to extract his corneas in Rizhao, Shandong Province. Photo: CFP

Cultural, bureaucratic constraints

Under Chinese law, consent is needed from donors as well as all of their lineal relatives before an organ can be donated. Since 2007, transplants from living donors, except spouses, blood relatives and step- or adopted family members have been banned.

"Even if a donor is registered, their organs can't be accepted if a lineal relative opposes," said Gao.

One reason for the small proportion of Chinese registered as organ donors is its associated cultural taboo. In Confucian ideology, a person's body is believed to be derived from their parents and thus donating one's organs, even after death, can be considered an insult. Another superstitious belief holds that the body must be interred intact for a person's soul to be received in the afterlife.

Aside from suffering a shortage of donated organs, China also lacks adequate personnel needed to supervise transplant arrangements. Currently, only Tianjin and Zhejiang Province have specialized organizations in charge of overseeing donations. Elsewhere in selected parts of the country, the RCSC is responsible.

Photo: IC

Thriving black market

Among people waiting in the small CODAC office in Dongcheng district last week was Ma Xiangxiang, who told Metropolitan she wanted to "sell" her kidney. Cradling her 1-year-old son in her arms as she stood anxiously next to her husband, Ma explained their dire situation.

"Our son has cerebral palsy. My husband can't work because he is in poor health. I want to sell my kidney and use the money to treat my son," said Ma, a 22-year-old originally from Shaanxi Province.

When Ma was seen by a CODAC staff member she heard disappointing news: It is illegal to profit from organ donation.

China's shortage of organ donors has led the black market to thrive. It is a tempting option for desperate people, like Ma, to make quick money. "I've never considered selling my organs on the black market. I really hope I can find an NGO that can help treat my son. I have nowhere else to go," said Ma.

Finding an organ dealer on the black market is only a few mouse clicks away on instant messaging service QQ, where there are groups run by users eager to chat to anyone willing to go under the knife.

In an undercover investigation, Metropolitan contacted two dealers seeking kidney donors. The sum for such a transaction was quoted at 35,000 yuan ($5,630) plus an unspecified bonus in the form of a hongbao (red, money-filled envelope).

The ideal donor was advertised as being aged 18 to 28, weighing less than 80 kilograms and at least 1.7 meters tall.

"Type O blood is most preferred. Height is negotiable," a dealer, using the QQ username "yangfudashao," told Metropolitan in an instant message. The dealer also promised to arrange for the operation to take place in a public hospital, explaining certificates could be forged to pass off the donor as a relative of the recipient.

New lease on life

China's announcement in August 2013 that it would phase out using organs of executed prisoners won international praise, but the move has put "more tension between supply and demand" on the fledgling national system, said Gao.

"We need to do more work raising public awareness about organ donation," he said.

In March, CODAC's official organ donor website was launched. The government also merged the Organ Transplant Committee and the China Organ Donation Committee to optimize operations.

Li Yuhai, 60, is eager for public awareness to continue growing so those who suffer organ failure can be as lucky as he was in August 2005 when he received a new heart. Li, who prior to his transplant battled cardiac dilatation, a condition where the size of the heart cavity becomes enlarged and stretched, has never been able to thank the family of the anonymous donor who saved his life.

"I feel like I've been given a second life. If I hadn't received my transplant, there is no way I would be alive today," said Li, who only waited two months before receiving his new heart. "I know that it's getting increasingly harder for people on the waiting list to get an organ. When my time is up, I will donate all my organs to give someone else a second chance."