What if China has a Fukushima?

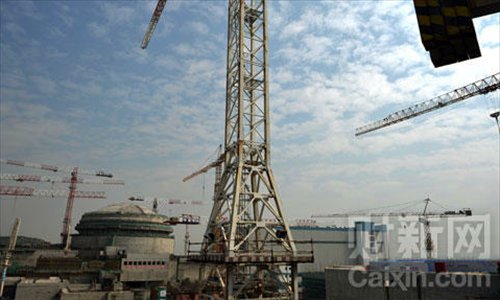

Photo: Caixin.com

China has never suffered a Three Mile Island-like nuclear power plant accident, much less a Chernobyl meltdown or a Fukushima disaster.

But now that the government under Premier Li Keqiang has put the country on a fast-track for nuclear power development, with dozens of new reactors scheduled to launch by 2020, the insurance industry is focusing attention on the difficult question "what if?"

China's insurers have been taking a cue from the National People's Congress, the nation's top legislature. A special panel under the NPC's Environmental and Resources Protection Committee was recently ordered to draft a nuclear safety law, the nation's first, with a built-in framework for power plant accident compensation.

NPC Standing Committee Vice Chairman Shen Yueyue said in February the law has reached the legislative agenda.

Zuo Huiqiang, general manager of the Chinese Nuclear Insurance Pool, expects the law to be enacted within two years. The 15-year-old CNIP is a collaborative effort of 25 Chinese insurance companies including China Reinsurance Group, Peoples Insurance Company of China and Ping An Insurance Co.

"During the early period for nuclear power development," Zuo said, "coming up with plans for what to do if something goes wrong is the responsible thing to do."

Certainly, there's plenty of work to be done in the insurance arena to make sure China's has a compensation response plan in place before an accident occurs. For example, liability caps for China's nuclear accident insurance policies are now the lowest in the world.

Under a 2007 State Council directive spelling out nuclear accident compensation plans, any of China's 19 nuclear power plant operators such as China Guangdong Nuclear Power Holding Co.(CGN), operator of the Daya Bay Nuclear complex in the southern province of Guangdong, and China National Nuclear Corp. (CNNC), which runs the Qinshan nuclear power plant in the eastern province of Zhejiang, must have insurance that covers financial losses and injuries up to 300 million yuan. If a legitimate compensation claim exceeds that maximum liability, the central government will provide up to 800 million yuan extra to cover the costs.

"Liabilities of 300 million yuan or less are to be assumed by nuclear operators, and the government is responsible for the next 800 million," Zuo said. "Even though there's no clear wording for anything over 1.1 billion yuan, the public nature of nuclear accidents almost definitely means that the government will bear the burden."

Thus, the 2007 directive in effect is a form of government policy support for the nation's nuclear plant operators. But because of the nation's liability caps, the level of support is relatively modest compared to what's in place in other countries that use the atom to generate electricity.

Limited, Unlimited

China's limited liability insurance system stands in sharp contrast to the unlimited liability coverage that protects the public in Germany, Switzerland, Japan, Belgium, Russia and the United States.

All other countries with nuclear power around the world, including Britain and Spain, have a limited liability system like China's.

The Chinese insurance pool's direct underwriting capacity is a respectable US$ 898 million, behind only Japan, Britain and Switzerland. In terms of compensation caps, Belgium has the highest at US$ 1.5 billion, followed by Japan and Switzerland at US$ 1.2 billion each.

In China, a lot more money would be needed to cover damage in the event of a major catastrophe.

"If there's ever a problem, this liability limit will certainly be too low," said Liu Yubo, CNIP's deputy general manager.

The price tag for the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan has been estimated at US$ 64 billion, while the cleanup alone after the Three Mile Island incident in the United States in 1979 cost about US$ 1 billion.

In Japan, a law in place when a tsunami struck the Fukushima plant required that the government make a one-time payment of US$ 3 billion to victims of leaking radiation. The plant's operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co. was legally responsible for most of the accident's costs and, as a result, might in the future come under state control so the utility can fulfill its obligations to accident victims.

Indeed, in many countries insurance companies get around the problem of catastrophic liabilities by working closely with one or more government entities willing to help cover extraordinary costs beyond the scope of insurance policies.

Catastrophic insurance coverage around the world is generally supported with a mix of public and private funds. This keeps insurance policy premiums for commercial nuclear power plant operators at reasonable levels. But finding the right balance can be difficult: Premiums have to be affordable, but coverage levels must be high enough to adequately protect against potentially enormous claims.

On top of that, the market's role in pricing is muddled in China because disaster management tasks are tightly controlled by the government.

Historical data is often used by insurance companies to set rates and write policies. But since China has little experience with nuclear accidents, there is a dearth of statistics. Moreover, data is hard to collect in China given the country's huge population and geographic diversity.

A strong interest in crossing the data gap was one reason behind the formation of China's insurance pool, which started with four companies and now has 25 – including 20 insurers and five re-insurance firms. In addition, China participates in an international nuclear insurance pool system that helps firms share experience, swap risk-related data, and learn about technological developments in the nuclear safety arena.

In countries that limit insurers' liability, compensation caps for nuclear plant operators can range from US$ 150 million to more than US$ 1 billion. Spain's liability is 1.2 billion euros, while the British government recently hiked its top liability to 1 billion pounds from 140 million pounds.

Countries with unlimited liability systems can rely on healthy and well-financed insurance pools, said Eero Holma, who chairs the General Purposes Committee of international nuclear insurance pools.

Among domestic pools nuclear insurance coverage, Japan's includes a fund for catastrophic accidents. A percentage of all premium payments is regularly deposited into this "catastrophic event preparedness fund." But international pooling provides another level of protection.

"Following several decades of international testing," Holma said, the nuclear insurance pool system (was found to be) the best method for dispersing major nuclear risks of a public nature."

Indeed, over the past 50 years or so, the pool has paid claims connected to more than 1,000 incidents linked to nuclear accident damages. These included Three Mile Island and the 1997 Tokaimura nuclear accident in Japan, after which the international insurance pool system paid the maximum compensation allowed under insurance claims.

Participating in the international pool are more than 272 insurance companies. The system is comprised of some 26 funds covering 27 countries where nuclear power plants are operating.

These pools are designed to protect businesses that could be affected by a nuclear power plant accident, as well as share information about safe technology.

Legal Gap

China has no such catastrophic accident fund built into its domestic insurance pool. Moreover, China is the only country in the world that operates nuclear power plants without a law that sets clear requirements for nuclear accident insurance liability and compensation levels.

Some industry watchers have suggested CNIP create a catastrophic fund like Japan's. They say the government could encourage such a system through tax exemptions.

The first step on the road to orderly insurance protection from nuclear accidents, however, will likely come in the form of legislation now being written by the NPC panel. The pending law is expected to clarify the scope and definitions of damages, responsible parties and liability limits.

At a March meeting attended by legislators and political advisors, Li released a government work report signaling Beijing's plans to accelerate building nuclear and hydroelectric power plants. Wang Yumin, deputy director of the National Energy Administration, told legislators the first power plants in this wave will be built on the country's east coast and "inland nuclear plants will be included in the next five-year plan" period, which begins in 2016.

But the low liability cap is "undoubtedly" a "mismatch with China's ambition to build the most nuclear power plants in the world," said Zuo.

Holma said China could draw lessons from other countries such as Switzerland, which initially had a low compensation standard.

When Swiss lawmakers were writing the nuclear insurance law currently on the books, they solicited opinions from the insurance industry. Switzerland eventually established a system with one of the world's toughest requirements for nuclear damage compensation.

Zuo says China appears to be heading down a similar path.

"The drafting of the nuclear safety law offers us an opportunity," Zuo said. "China should grab this opportunity and raise the compensation limit."