Confucius Institutes have Uzbek students looking east

An Uzbek student practices Chinese calligraphy at the Confucius Institute in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on June 4. Photo: Wang Wenwen/GT

The Confucius Institute is often viewed as soft power tool for China to gain cultural influence across the globe. But for students in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, it is simply a matter of cultural interest.

Opened in 2005, the Confucius Institute in Tashkent is the first in Central Asia, where currently over 400 students ranging from ages 6 to 55 attend daily classes in Chinese-language and culture.

Olim Shermatov, an English and French teacher at the Uzbek State University of World Languages, is the oldest student at the institute. A student of Chinese for three years, Shermatov explained he developed a love for Chinese culture through kung fu, which he studied in Uzbekistan during the Soviet era.

He is also studying Chinese calligraphy, which he feels shares similar principles with martial arts.

“Sometimes you need to do it hard and sometimes softly. It is a matter of yin and yang. It is also the essence of Chinese culture.” Olim said.

Sayora Mamadalieva, 38, has been teaching Chinese at the institute for four years and is a favorite among students.

At first, she found pronunciation the most difficult hurdle in learning the language, but after a year of study in Beijing and another two in Shanghai, she now speaks fluently.

Besides working as a part time teacher at the Institute, she also trains employees at local companies that deal regularly with Chinese clients.

“I’m one of many witnessing the growing interest in China and the Chinese culture and language among Uzbeks,” Mamadalieva told the Global Times.

Confucius Institutes are often hosted by a local educational institutions, which is then paired with a Chinese university to provide teachers and instructors.

Lanzhou University in Gansu Province has sent a number of language teachers since 2005 to the host institution Tashkent State Institute of Oriental Studies in Tashkent.

However, it has not always been easy, as some Confucius Institutes have encountered difficulties in some foreign countries. In 2012, Confucius Institute instructors in the US were denied visas on the grounds they did not meet the prerequisites for obtaining teaching accreditation. Some voiced they were denied out of fear of China’s influence.

Hou Suling, one of four language instructors who has taught at the Tashkent institute for half a year, told the Global Times that there might have been some concerns on the Uzbek side as well, which makes their work difficult.

Last year before arriving in Tashkent, she had helped her Chinese colleague who worked at the Confucius Institute initiate a summer study abroad program that would send Uzbek students to China.

But administrators at Tashkent State Institute of Oriental Studies ultimately blocked the program for concerns of student safety.

“We thought it would be good for these students, but [the administration] didn’t think so. Perhaps it’s just a matter of miscommunication,” Hou said, adding she hasn’t given up hope and will apply for the program again this year.

“Everything at the beginning is difficult, and we just try our best,” she said.

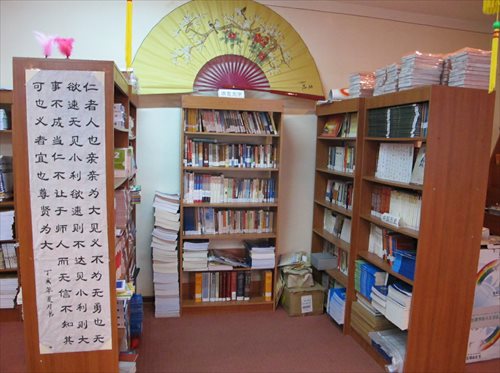

A library in the Confucius Institute Photo: Wang Wenwen/GT