‘Manuscripts of Qian Zhongshu’

Notes by famed writer allow a look into the mind of a master

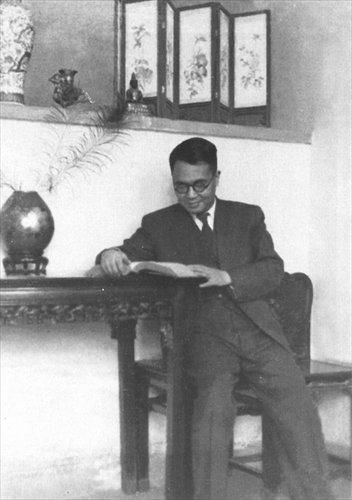

Qian Zhongshu

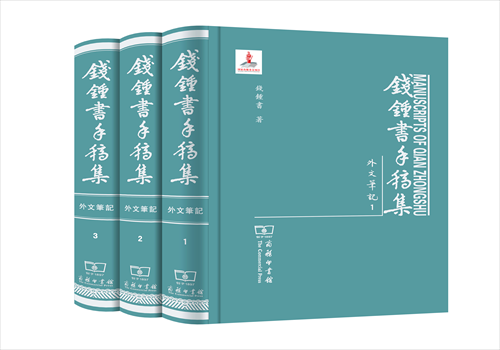

Inset: The first three volumes of Foreign Language Notes, a part of the larger series Manuscripts of Qian Zhongshu Photos: Courtesy of The Commercial Press

Through works like A Town Besieged and The Marginalia of Life, the late literature master Qian Zhongshu (1910-98) managed to leave an indelible footprint on modern Chinese literature. While many admire the wisdom embedded in his masterpieces, few know how this writer came to be such a master. Now, with the publication of 211 of his notebooks containing a total of more than 35,000 pages of his personal thoughts, we may finally get a chance to see the tip of the iceberg of his genius.

An avid reader who spent more time reading than actually writing, Qian took notes on and made comments about every book he read. Proficient in multiple foreign languages - English, French, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish and Greek - he was able to read books from all over the globe that ranged from philosophy, linguistics, psychology and anthropology to literature.

These copious notes have been kept safe by Qian's wife Yang Jiang, also an influential writer in China in her own right. In 2000, Yang reached an agreement with The Commercial Press to photocopy and publish these notes in book form. Titled Manuscripts of Qian Zhongshu, the first part of this huge series Notes in Ronganguan, consisting of three volumes, was published in 2003, while the second 20 volume set, Chinese Language Notes, was published in 2011.

As for the remaining portion of Qian's notes, the largest and most valuable section that records his thoughts on his readings in foreign languages, these are set to be published in a set of 50 volumes titled Foreign Language Notes, the first three volumes of which were already published in June.

Keeping a record

"Many people say Qian was gifted with an extraordinary memory. However, he didn't believe he was all that incredible. He merely loved reading, not just reading, but also taking notes. He wouldn't read something just one or two times, but three or four times, constantly adding new things to his notes. That's the real reason why he never forgot all those books he read," Yang, now 104 years old, wrote in the preface of Manuscripts.

As a youth, Qian attended Tsinghua University in China as well as Oxford University over in England. After coming back to China, he returned to Tsinghua to teach literature. According to Yang, his habit of taking notes developed while he was reading in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

Since the books in the library couldn't be removed from the premises nor could any marks be made on the books themselves, Qian decided to write his thoughts down in notebooks while he was reading.

Of course this method meant it took nearly twice the time than usual to get through a single book. Yang explains in the preface that countless books were constantly coming in and out of their home over the years, with only these books of notes Qian's only form of permanent storage. "These notes are already 'useless' to him, but for those who study foreign literature and Qian's works, are they really that useless?" Yang wrote.

These notes cover the books that Qian read from the 1930s all throughout to the near end of the 20th century when he passed away. An inseparable part of his life, his passion for literature, languages and knowledge are all preserved in these writings.

Massive undertaking

Although outliving both her daughter and her husband has been painful for Yang, this has not stopped her from taking on the job of passing on Qian's work after his death. However, she realized that this was a task she could not accomplish on her own. Brought in by Yang, German sinologist Monika Motsch, the translator of the German version of A Town Besieged, was among the first group of people to get a chance to see Qian's grand work.

Motsch first saw Qian's notes in 1999 when, half a year after his death, Yang invited Motsch to help arrange and catalog all of the late author's notes.

"The writings in Foreign Language Notes are an unprecedented 'world of miracles.' They don't separate China and the world, but connect them together like the Great Wall," Motsch wrote in the introduction to Manuscripts.

Arranging such a massive amount of material seemed nearly impossible at first. Both Motsch and her husband Richard Motsch, who between the two of them speak six languages, were both involved in organizing all the notebooks.

In the end they chose to rearrange these notes into six parts: The first four parts according to chronological order, the fifth part consisting of scattered pages of notes and the sixth covering personal journal entries.

The three volumes published in June, cover the notes Qian took from 1935 to 1938 while he was studying in Europe. According to Monika Motsch, Qian took notes in English about books on literature, philosophy, art history and psychology during his first year studying overseas. These notes cover works from famous writers such as Richard Aldington, T.S Elliot, Owen Beburd, George Santayana, Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. Later, French literature begins to appear in his notes, covering authors such as Victor Hugo, Gustave Flaubert, Saint Beuve and Alphonse Daubet.

"The excerpts that Mr. Qian has written are unexpected and fresh, even to us Europeans. We grew up with the works of these Western writers, so are already familiar with them. Still we were very impressed by the wisdom of his views," Motsch wrote.

In this age of high technological convenience, a time when people are even gradually forgetting how to write by hand, Qian's huge handwritten work that he kept at throughout his entire life is the perfect inspiration to get modern people to reflect.

"The knowledge he pursued assiduously for his entire life should be a useful heritage for those who study his works and Chinese and foreign literature. I will do all I can to preserve these notes and diaries that he left for those who pursue knowledge," Yang wrote.