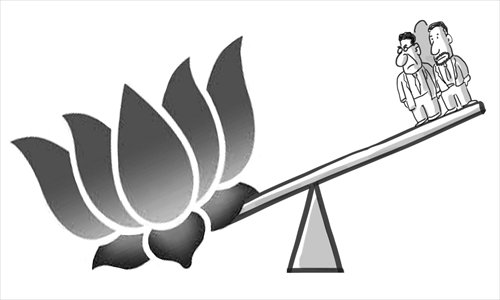

BJP member drive raises one-party concerns

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), now in power in India, wants to become the world's biggest political outfit. The membership drive, kicked off by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on November 1, is slated to run until March 31 next year. If it manages to triple the number of members by then, its stated goal, the BJP might surpass the Communist Party of China's 86 million members.

This is not an unrealistic aim. In the Lok Sabha elections held in May, the party polled 170 million votes. The calculation within the top echelons of the party is that even if over half of these voters can be converted into full-time members, the BJP can easily achieve the objective of having over 100 million members.

The party, however, is not satisfied with just numbers. One of its vice presidents, Vinay Sahasrabuddhe, told me, "Post-March 2015, we intend to build on the membership drive by holding a mass contact program and conducting orientation training for our new members. The intention is to make them aware of the party's policies and philosophy." He pointed out that modern technology now enables political parties to be transparent about the process of membership. "Mobile phones allow us to give free membership to all those who intend to be part of our drive. Technology also eliminates the possibility of fraudulent membership," he added.

The BJP may be upbeat about its new-found support but there are muted voices expressing fears about the party turning into a political hegemon in coming years.

Already, during two recent state elections, the BJP has turned the tables on its allies by emerging as the first party of choice and reducing the allies either to junior partners or rendering them completely irrelevant.

For instance, the Shiv Sena, a dominant partner in Maharashtra for over a quarter century, is now very much a smaller part of the new government in that state. The Haryana Janhit Congress, a former ally of the BJP that walked away from the alliance, is now marginalized, with the BJP winning a majority on its own for the first time in the state of Haryana's history in November. There are speculations that the Shiromani Akali Dal, one of the BJP's oldest political allies, may also face the heat by the time state elections come round in 2016.

This has given rise to a fear among a section of political observers that BJP's phenomenal rise does not bode well for India. The world's largest democracy, they contend, must have more diverse representation, not single-party rule. But the BJP brushes aside these fears. "We are a political party and we have the right to expand our base, no matter what our detractors feel or say," another party leader asserted.

In the short run, the BJP will certainly emerge as the most dominant political outfit as the party takes advantage of the winds blowing in its favor.

India has seen a single-party monopoly in the past too. In the first 20 years after India attained independence, the Congress party was unrivalled. But post-1967, other smaller parties started to make inroads.

Right now however, the BJP is the first choice for most Indian voters, leaving the Congress party, its biggest pan-India rival, far behind. In fact, the Congress has never formally put a number on its membership, although it is perhaps the oldest political party in India. In the years during India's freedom struggle in the first half of the 20th century, the Congress party was run more like a social movement rather than a well-organized political machine. It is therefore not a surprise to see that the Congress party has never been able to count its members. No matter how many of them there are, however, they may soon be outstripped by the BJP's push to be the only game in town.

The author is a freelancer and a commentator on strategic and defense issues in India. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn