Urban intellectuals try to revive village life

Young Chinese intellectuals are trying to return to their hometowns, reviving the village life they remember from their youth. But in the teeth of deserted villages and growing agribusiness, it's proving a hard task.

Chen Tongkui and villagers from Boxue village visit a Taiwan village in January this year.

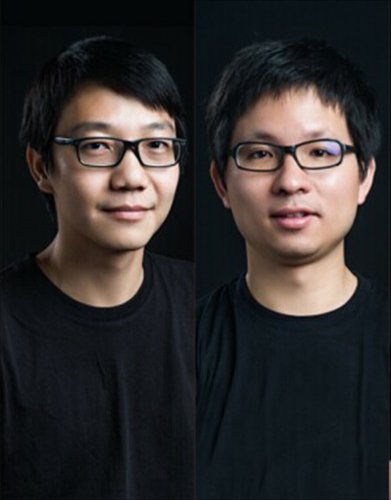

Inset: Chen Tongkui (right) and Liu Jingwen

Inset: Pineapple tarts made by Boxue villagers Photo: Courtesy of Chen Tongkui

Chen Tongkui says this may be the lowest moment of his life.

Five years ago, inspired by a Taiwan village's success on community development, he started to build his hometown, an old hamlet of 300 villagers in South China's Hainan Province, into an ecological community that can develop rural tourism and create work opportunities by attracting urban residents who desire for a healthy, green farm life on their weekends and holidays.

His home village of Boxue has bad crop conditions and the basic infrastructure was poor.

In the past five yeas, he has made some achievements, such as improving the basic infrastructure, drawing in visitors in and out of China, and building a track to host bike-racing events. He roughly transformed the village from a poor remote countryside into an attractive place.

Chen said he achieved all the promises he made to the villagers five years ago, but still, his plan is a failure.

"The village is still deserted. Young people are still leaving. Villagers are no longer as close as before, only caring about their own interests. The village committee, a self-governing organization in the rural areas but plagued with corruption, failed to connect people," Chen, who used to be a reporter at the Guangzhou-based Nanfang Daily, told the Global Times.

"The old structure of the traditional villages is disappearing."

Chen quit his job as a senior journalist in 2009 and devoted himself to changing the neighborhood where he grew up.

Chen is not alone. There are increasing numbers of young intellectuals who came from the rural areas and oppose modern agribusiness, returning to their hometowns and wider rural areas to participate in village renovation. They have brought in a fresh air of maintaining the traditional way of agriculture, and help to keep farmers on the land by increasing their incomes.

They have experimented with different methods of rebuilding villages. Some have used their social resources and collected money to fully engage into the community rebuilding. Some have tried to solve rural problems by new economic methods. Some established companies to sell organic food produced by the farmers online.

Ecological village

Chen misses the traditional lifestyle in China's rural areas where people were closely connected and villagers lived on the farm when he was young. He also recalled, when he became the first college student from the village, how all the villagers hosted a banquet and collected money for his tuition fees and living costs.

"This was the sort of village in my deep memories," Chen said.

The current situation in the rural areas saddens him. Many centuries-old stone houses were demolished. Old trees were chopped off. Young people left villages to become migrant workers.

"Farmers should return to the land. They should be capable of raising a family by farming. This is how we can rebuild the community and let villagers live happily on their own land."

When Chen was invited to visit a village in Chinese Taiwan that was once a poor hamlet but has now become an ecological tourism destination that drew in 22 million yuan ($3.53 million) revenue by developing tourism, he was inspired.

Chen's village was poor but had a long history. The average annual income was just 2,000 yuan and farmers lived off their own produce.

Chen firstly was determined to copy the success of the Taiwan village.

Earning trust from the villagers came as the top priority. In 2009, he returned to his village and set up a development council that involved 20 capable men in the village as council members. The council adopted a democratic voting process.

The council received a welcome from the public soon after Chen refused a large bribe from a real estate developer who wanted to build the village into a golf resort.

With support from the villagers, Chen and his council soon repaired a road, held a bicycle-racing event and built some ecological fruits gardens with the aid from Taiwan villages. The environment and the basic infrastructure improved a lot. In 2012, a group of artists from South Korea visited the village.

Gradually, Boxue became known to the public after media exposure.

Village coup

However, Chen's renovations faced problem after the village head changed.

"I realized, my projects went smoothly when the village head was wise and open. After the new village head who had a closed mind took office, the operations of the council were suspended," Chen said.

The growing reputation of the council has somehow threatened the power of the village head who practically seized power, Chen said.

Without support from the village head, Chen had to seek other ways.

This year, the operation of the council was suspended, because Chen found that it was practically impossible to continue reforms.

That's when Chen began to further think about the complicated profit distribution in the rural areas and started to shift direction.

Reviving the traditional relationships between farmers and the land has become a long-time issue given the context of massive urbanization.

In the past decade, social change has intensified the urban-rural conflicts and left the rural areas deserted.

It has caused severe problems, such as the influx of the migrant workers that burdens the capacities of the city, and old people who were left without family in the rural areas.

As with intellectuals in the 1920s who attempted to revive the countryside, a wave of young people, including Chen, began to ponder on how they should save their home villages.

Experts praised these campaigns. Yang Tuan, deputy director of Institute of Social Policies of China Academy of Social Sciences, said there are mainly four different groups of people who lead renovation in the rural areas, the migrant workers, young people who are highly educated, the successful people who came from the villages and NGOs.

"They want to end backwardness in the rural areas and keep farmers on their own land, which deserves encouragement. By passing on the positive energy, they could influence more people to participate," Yang Tuan, told the Global Times.

E-commerce

When Chen was rethinking his community rebuilding strategy, Liu Jingwen, a former senior editor of Guangzhou-based Nanfang Daily, found a shortcut: help farmers to sell their products.

Liu is worried about the disappearing of the traditional farming. Born in Zhanjiang, South China's Guangdong Province, he had witnessed the disintegration of the traditional rural society in his home village. Compared with villages in eastern China, Liu believes, the remote areas in Xinjiang needed more help.

Liu, who had a chance to visit Xinjiang, felt inspired to help local villagers to sell dried fruits and nuts online. So far, he has established 15 farmers' cooperatives in Northwest China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

"People in south Xinjiang still adopt a traditional way of farming. They respect the land and its relationship with humanity. But the biggest problem is how to sell the agricultural products and make money," Liu, told the Global Times.

However, due to the language barrier and religious differences, Liu found changing the local people's mind and make them understand the e-commerce was important.

"The first step was to change people's mind. For a few centuries, smallholder and its economy and consciousness have been a shackle to innovation. Most of them live their lives following a natural way. That was how we should start to change," Liu told the Global Times.

Liu also mentioned, he hoped by developing the farmers' cooperatives, the later generations of the farmers need no longer to work in the cities as migrant workers. "Farmers should be capable of earning a life by farming. The later generations should live a decent life," Liu said.

At the very beginning, Uyghur villagers didn't trust that Liu would realize his promise of helping to sell the products, so they were not actively participate into the cooperatives.

The situation began to change when Liu started to select some respectful local people who were knowledgeable and understood e-commerce to establish a "trust system." Local farmers started to participate.

Now, Aji, a local youngster, has become Liu's partner and taken responsibility of connecting the 15 cooperatives in Xinjiang. Liu hoped more and more local youngsters can return to their hometowns and make contribution.

Setting up cooperatives is a costly affair. Sometimes, to help change the society, Liu had to balance the economic benefits and public affairs of the villagers.

"I never said I am doing charity. I have to ensure the operation of the cooperatives, and in the meantime, I also have to take care of the public affairs," Liu said.

The cooperative purchased agricultural products at a price 10 percent higher than the market price, to at least ensure the farmers' interests. Liu has also launched classes to train local farmers in how to improve their agricultural skills and ensure the quality.

Now, over 2,000 households all over Xinjiang cooperate with Liu.

Liu started a new project this year, letting people adopt jujube trees. "Let us return to the farmland together. By cooperation with the farmers, we gradually came to know how much we had no idea about the land and the agricultural products on the earth," Liu said.

Balance of interests

Yang Tuan says people who are engaged in the village rebuilding have something in common.

Most of them were born after the 1980s, and lack the traumas of earlier generations, but they have encountered the same dilemmas.

"Escaping rural life in the teens, they also felt it hard to reach the core issue among the farmers and in the rural society simply relied on their own capability," Yang said.

This year, Chen explored a new way and decided to shift his focus from community rebuilding to the selling of local lychees. Beforehand, he had survived on a grant from a research center in Shanghai.

This year, Chen earned 200,000 yuan after selling lychees, but he used 110,000 yuan to invite villagers to visit the Taiwanese village that had encouraged him. "They have to go out to see how others are doing, so that their mind could be encouraged," Chen told the Global Times.

"We're not giving charity. We want to stimulate farmers and make them stand out to speak for themselves," Liu said.

Newspaper headline: Lost country