How a Tibetan monk brings free education to herdsmen’s children with cheese revenue, govt funding

For 20 years, a Tibetan monk-cum-teacher in Qinghai Province has explored a new way to combine traditional and modern educational methods to open new horizons for the children of poor herdsmen. His success story has shown how a community can improve itself through social responsibility, ideas of equality and hard work.

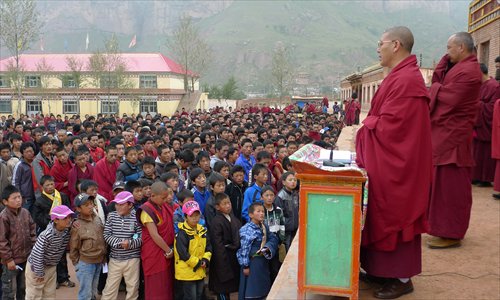

Headmaster Jigme Gyaltsen delivers a speech at a weekly school gathering. Photo: Courtesy of Jigme Gyaltsen Welfare School

There is a popular Tibetan saying: Every mountain, every river, every lake is sacred. And in every mountain, there live sacred souls.

Ani Gongqun Mountain is located in Golok Tibetan Prefecture, 400 kilometers, or eight hours by mountain road from Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province. Unlike other mountains on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Ani Gongqun seems rough, desolate and calm, yet it has its own soul.

In Tibetan "Ani Gongqun" means "big bird spreads its wings." Indeed, it has wings. It stands watch over the Yellow River flowing before it and pilgrims turning prayer wheels at the 240-year-old Ragya Monastery.

At dawn, when the first rays of morning sun hit the golden roof of the monastery, bells toll and monks chant.

About 300 meters from the monastery, on the campus of the Jigme Gyaltsen Welfare School, students - both monks and lay learners - flood into their classrooms.

Tibetan monk and headmaster Jigme Gyaltsen, 49, stands in the middle of the campus and greets the students.

"Sangjie, keep up your studies, be more disciplined."

"Rengdan, are you feeling better? Make sure you stay warm."

"Gesang, how's your father. Is he OK now?"

He knows every student's name, where they come from, their problems and how hard it was for them to get into his school.

Knowledge can transform

Every September, thousands of applicants come to the school accompanied by their parents from other parts of Qinghai, Tibet, Sichuan, Gansu, Inner Mongolia, with some traveling thousands of kilometers to wait outside the school's main gate.

The school receives over 1,000 applications every year, but only 200 students can be enrolled. Enrollment is on a first-come-first-served basis with no exceptions; a close relative of the headmaster had to wait for three years to get into the school.

Twenty years ago, the school was founded with 3,000 yuan ($480) of Jigme's own savings, 130,000 yuan of loans, and Jigme alone teaching 80 students. Now it has more than 900 students and 38 teachers, one third of whom are Buddhist monks. There are no tuition fees and all accommodation is free.

"I started the school based on the idea of education for all," he told Global Times. "Many of the children of herdsmen don't have the chance to be educated. My purpose is that through learning both traditional and modern subjects, in the end, knowledge will elevate and transform us."

The youngest student at the school is 6 years old, while the oldest is 42.

"When the young and old study and live together, the young will learn a lot of things from older students. They will discuss things freely and be inspired to learn from each other," the headmaster said.

Above left: Headmaster Jigme stands on the bank of the Yellow River. Across the river is the overview of the whole school. Photo: Courtesy of Jigme Gyaltsen Welfare School

Awakening minds

Apart from courses on mathematics, physics, Chinese, English, computer technology and music, the school integrates many aspects of traditional Tibetan culture into the curriculum - Tibetan Buddhist logic, debating techniques, Tibetan classics, Tibetan medicine, Tangka painting and traditional architectural design.

Buddhist Logic (Hetuvidya) debates are key to the success of the school. Buddhist rational debate methods are applied to almost all academic disciplines at the school.

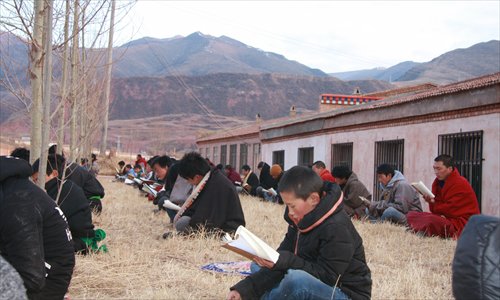

Every day, students spend 30 minutes at noon and 40 minutes in the afternoon debating their newly acquired knowledge with their classmates and teachers.

"Debates are extremely helpful to summarize what we have learned during the day. They help me to consolidate my knowledge and to inquire further and deeper, " says Gengdeng Zongzhi, a student at the school.

"Tibetan monastic learning does not only stress reciting and memorizing, it also encourages creative thinking," said Cizhi Jiacuo, the school's deputy headmaster. "Students are encouraged to question each other and their teachers. Debates awaken students' minds."

Each Thursday there is a festival on the campus in which all of the teachers and students dress up in traditional Tibetan robes. There are quizzes on poetry, religion, math, law and science. The English class performs a play, while others recite Chinese poems. A few perform a fragment of the classic Tibetan epic of King Gesar and some compete in Tibetan calligraphy and painting.

"Buddhist debate and weekly contests represent the openness of knowledge, releasing creativity. It is the organic combination of both traditional and modern educational advantages. It aims to encourage students to gain self-consciousness, creativity and sharpness." wrote noted education expert Yang Dongping on his blog after visiting the school.

Above right: Students recite Tibetan grammar. Photo: Courtesy of Jigme Gyaltsen Welfare School

A labor of love

While academic work exercises the mind, the challenges faced by the school lead to students and teachers often getting a good physical workout.

The school's tap water supply is unreliable, so water is carried by students and teachers from the Yellow River. In winter, the main heating material is cow dung that the students collect on the prairie.

"Construction materials are expensive. Labor costs are high. We need to repair the dirt road every time it rains. Each tree was planted by students. Each wall, each road, was built by teachers and the students together," the headmaster said.

Under the guidance of their teachers, students help to build their own school. If there is road they need to repair, it is a labor of love. Starting early in the morning young students clean roads and plant trees while older students move stones.

On these days hundreds of songs are sung. During their hard work, they sing upbeat tunes with lyrics about horse racing and herding; during their break, they sing slow songs about their homes, the prairies and mountains, and their teachers.

Text for the best

Apart from teaching the national standard compulsory textbooks, the school holds open seminars and its teachers write and edit supplementary textbooks on traditional literature, religious classics, grammar, English and medicine.

Every month, there is a school-wide ethics seminar delivered by a scholar. Cizhi Jiacuo was once a main speaker of the seminar. He is not only the deputy headmaster, but also a well-known Buddhist scholar. His talk covered a wide range of topics, and he combined his profound knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism with the philosophies of Confucius, Nietzsche and Jung to deliver a talk that aimed to open the minds of the listeners.

English teachers have organized a textbook writing team to compile new textbooks suitable for their rural students.

"Standard English textbooks are mainly about the city. We compile supplementary textbooks suitable for herdsmen and farmers. Our vocabulary and texts talk about snowy mountains, herdsmen, yaks and grasslands. These words and sentences connect with the daily lives of herdsmen's kids. It is more intimate and lively." says English teacher Dojie Zhaxi.

Such efforts and teaching methods bear fruitful results. The students have had more than 3,000 articles published in Tibetan language journals and more than 100 books published. More than 200 graduates of the school have become medical doctors, teachers and monastery administrators.

What makes the headmaster most proud is that, following his example, four graduates founded schools in their own hometowns. They seek to spread the ideas about education they learned at the school to other students.

Vital to educate girls

Due to the local geography, herdsmen live scattered around the mountains. Many herdsmen's children - especially girls - do not get the chance to have an education.

"The education of girls is for the mother, the education of mother is for mankind," Jigme says. He has always believed that in order to increase cultural standards it is vital to educate girls too.

Because of the strictures of Buddhism, the welfare school would not enroll female students. Yet many herdsmen wanted a place their daughters could study. In 1997, Jigme proposed that the Golok Education Bureau should allow him to found a school for girls. Four years later, the proposal was approved. The Prairie Talent Girls' School provides a place for girls to pursue knowledge just as the boys can.

After obtaining approval, Jigme tried all different funding methods to obtain the 3 million yuan he needed to run the school. He had an arrangement with the Golok educational authority. If the girls' school could enroll 40 students annually, in six years when the number of students reached 240, the government would provide funding. The second year the school was open, this goal was reached. Currently the government is one of the main sponsors of the girls' school, among other charitable foundations. The government provides 1,650 yuan of funding each year per student. The 14 teachers at the girls' school are on the government's official payroll. One of the deputy headmasters and the director of study are both graduates of the boys' school.

The teaching method at the girls' school are similar to the boys', and the girls also debate what they learn. Its playground is even bigger than at the boys' school. In academic competitions, girls' school graduates have achieved some of the highest scores in the prefecture.

The road ahead

Jigme's vision is not limited to education, but also stretches to entrepreneurship. In order to help the school provide a free education, he began to produce high quality cheese in 2000. With the support of European cheese experts, the company sells Tibetan Yak cheese. Though his company's production capabilities are limited, it was well-received abroad and is now exported to the US and Europe.

The Tibetan Yak Cheese Project was the starting point of his efforts to help his community through social entrepreneurship. In 2009, he started the Snowland Animal Husbandry Development Association to promote the efforts of local herders. "On the plateau areas, a tent, a family, they take care of themselves," Jigme explains to the Global Times. "Connecting them through economic cooperation can promote herders cooperation. These cooperatives actively work to promote local products. Individual families have been able to gain access to larger and more distant markets, providing greater stability and long-term sustainability."

It has been 20 years since Jigme founded the school. Through most of these years, almost all of the teachers - both monks and volunteers - have not received a penny. It is only since 2009 that teachers have begun to receive around 1,200 yuan as a monthly salary, funded by a Beijing entrepreneur.

After 20 years of trials and tribulations, the achievements of the school have shown the value of their teaching methods. It has shown that traditional culture need not to be abandoned in the pursuit of a modern education. It has also shown how a community can improve itself through social responsibility, ideas of equality and hard work.

Newspaper headline: Tell it on the mountain