Myanmar national reconciliation challenged

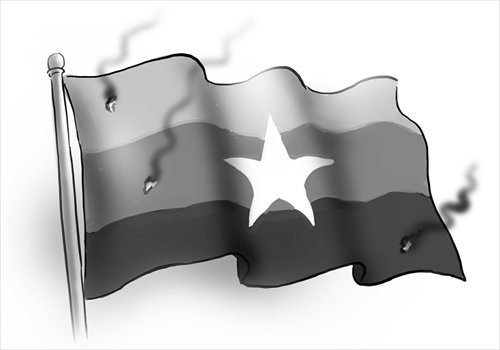

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

At the start of 2015, the situation in northern Myanmar's Kokang region became tense once again. In December 2014, Pheung Kya-shin, who claims to be the "King of Kokang," returned after laying low for five years. He declared the revival of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) composed of around 1,000 ethnic Kokang fighters and vowed to retake the Kokang territory. On February 9, fighting between the MNDAA and Myanmar government troops began.

The dozens of skirmishes so far have caused more than 130 casualties and sent tens of thousands of refugees fleeing. Myanmese President U Thein Sein signed two notices on February 17 declaring a 90-day state of emergency and imposing martial law in the embattled region. Though Mya Htun Oo, spokesman for Myanmar's Defense Ministry, announced at a press conference on February 21 that government troops had imposed a curfew and were in control of the situation, the two forces are still at each other's throats and tens of thousands of refugees have been displaced.

Through the battles in and surrounding the northern special region, Pheung aims at recovering his governing power in Kokang and gaining recognition from the Myanmar government, in a bid to seek legal political status and personal safety. Nonetheless, the government will certainly not allow Pheung to retake Kokang easily and therefore has assembled massive forces to strike the ethnic army. Meanwhile, it also expects such heavy strikes to deter the Kachin Independence Army, the Ta'ang National Liberation Army and other ethnic militias.

Thein Sein's government, which came to power in March 2011, has emphasized national reconciliation as a significant goal. To this end, the government has engaged in protracted negotiations with varied ethnic armed forces. Though both sides have made some concessions and reached a consensus on most terms of a nationwide peace agreement, they have failed to reach a firm conclusion.

The most critical reason lies in that government troops insist articles in the peace accord should not violate the 2008 Constitution and existing laws. Plus, several ethnic armed groups hope to control local resources and public security out of their own interests, which the central government finds difficult to accept. Therefore, the long-awaited peace agreement remains a mirage.

The clashes between government troops and the Kokang ethnic army took place in the Kokang territory and its surrounding areas, which have relatively little influence upon Myanmar's inland regions as well as the general elections later this year. Owing to a sluggish economy, lack of weapons and a demoralized army, the MNDAA is unable to sustain prolonged and large-scale battles but can only launch guerilla attacks. But given the thick forests and bumpy roads of northern Myanmar's Shan Hills, government troops find it hard to completely wipe out the MNDAA.

In addition, government forces cannot afford to be engaged in a large-scale military campaign in the light of the general elections slated for October 2015. It is predicted that conflicts between government troops and ethnic armed forces in northern Myanmar will not stop any time soon and the two sides will keep fighting while negotiating. Both sides are pursuing future bargaining chips on the negotiation table through success on the battlefield. For them, fighting and negotiation are both means to an end.

Since Myanmar declared independence in 1948, the last six decades have proved that force cannot solve the country's ethnic issues. The Myanmar government troops and the various ethnic armed forces should recognize the realities of the current scenario, render mutual understanding toward each other and go on with peaceful negotiations to address disputes. On the one hand, ethnic armed forces will get nowhere by attempting to control all the powers and resources within their territories. On the other, blind suppression imposed by government troops will fail to convince ethnic armies.

A proper power-sharing and interests-distributing mechanism is key to resolving the chronic conflicts.

The author is a professor at the School of International Studies at Yunnan University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn