Decades later, heirlooms for residency agreement still not honored

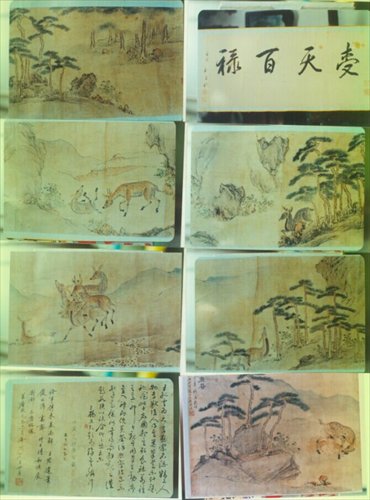

Ten Deers by Yuan Dynasty imperial court painter Wang Zhenpeng and the imperial edict which Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) gave to Xu's ancestors were part of Xu's heirlooms. Photos: Courtesy of Ren Fuxing

In August 2002, experts look at the annotated copy of Book of the Later Han, one of the most valuable items among Xu's heirlooms, in Shanxi Museum. Photo: Courtesy of Ren Fuxing

Twenty-six years ago, a government-run research society in Shanxi Province asked Xu Jinwei, a farmer, to donate the 293 pieces of his family heirlooms. Xu agreed on the condition that the government grant him a city hukou (residence permit) and a job in return. Decades have passed, and while the heirlooms are now under State ownership, Xu still hasn't got the status of his hukou changed. He also can't retrieve any of the heirlooms that his family protected for over 140 years.It was a gusty day 26 years ago, and wind carrying yellow dust whipped the small village of Dongjie in Wutai county, Shanxi Province. A minivan, fully loaded with antiques, paintings and works of calligraphy of the Xu family, left the home of farmer Xu Huiyun and her grandson Xu Jinwei, ostensibly headed for the Shanxi Culture Research Society in Taiyuan, the provincial capital.

On March 9, 1989, after a series of family discussions and negotiations with the research society, Xu Huiyun and her grandson donated 297 artifacts to the government-run research institution. The artifacts were the heirlooms of the family, who were descendants of Xu Jiyu, a high-ranking official and scholar in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

It was a decision that defied family instructions. "If you have to sell, sell property and land, not books, calligraphy or paintings," Xu Jiyu, the family patriarch, was recorded as saying before his death. And over the past century, Xu's descendants have tried their best at keeping the artifacts in top condition and had refused buyers when they showed interest.

What prompted them to make the decision was a promise to change the status of Xu Jinwei's hukou from rural to urban. This promise was made by officials from the provincial government and the research society.

In the 1980s, the government offered State-owned organizations limited quotas to change rural residency to city residency. City residency was sought because it usually meant better social welfare and higher social standing.

But that promise was never fulfilled, and the decision Xu Jinwei made 26 years ago would become the source of remorse that haunted him every day. Now 50 years old, his hukou status still hasn't changed, and he is unable to retrieve the artifacts he donated. What's more, 28 artifacts he donated went missing - they couldn't be found in the archive of any research society or organization.

Keeping the family heirlooms

"I'm the black sheep of my family," Xu Jinwei, standing in front of the grave of Xu Jiyu, says in remorse.

Xu is the seventh-great-grandson of Xu Jiyu, a high-ranking official and geographer during the late Qing Dynasty.

While political power helped the Xu family to gain prominence and wealth in the late Qing Dynasty, the following century saw it in decline, in part because Xu's reformist views were not in favor. Some went as far as calling him a traitor due to his open praise of Western government and democracy in his books.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Xu's tomb was smashed and raided by villagers, and his corpse was dug out and its clothes stripped off, according to an account by a witness in the village.

In the 1980s, Xu Huiyun, his fifth- great-granddaughter, found herself in a desperate situation. Her mother was over 90 years old, her daughter was blind, and her husband was sentenced to over 20 years in jail for serving in the army of Puyi (1906-67), China's last emperor, in the puppet state of Manchukuo. Arranging a good future for her grandchildren became her biggest concern.

The family's biggest asset was the heirlooms. Among the over one dozen paintings and works of calligraphy, the most valued one was Ten Deers, a painting by Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) imperial court painter Wang Zhenpeng.

In the 1980s, an interested buyer once offered a truck worth over 30,000 yuan, then a fortune in China, in exchange for the painting, but was turned down by Xu Huiyun.

It wasn't easy to keep the artifacts in good condition. Xu Jinwei recalls that during the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, he, still a teenager, would help his grandmother move the artifacts out of the basement every summer, when the temperature starts to rise, and dry them in the sun in their courtyard to prevent them from possible damage from moisture. The drying would last three days. All this had to be done in secret, in case other villagers found out about the artifacts.

After that, Xu would wrap the artifacts in oil paper and keep them in the basement again, "in case they got stolen or robbed," Xu recalled. "It was really difficult to keep these items in shape."

Donating the possessions

In the fall of 1988, Ren Fuxing, founder of Shanxi's Xu Jiyu Research Society, heard about the Xu's heirlooms. He approached the Xu family and asked to see the books and calligraphy.

"I was astonished [to see so many artifacts]," he recalled the first time he visited, when he marveled at the research value of these collections.

Ren then told his discovery to Liu Guanwen, vice president of the Shanxi Culture Research Society and the director of the Academy of Social Sciences in Shanxi Province. Liu then sent Ren and Cui Zhengsen, an associate, to buy the collections.

"We told them we would donate the heirlooms only if the government could give us a city hukou and find me a job," Xu Jinwei said.

Xu Huiyun also asked for a job in the legal system in the public sector for her grandson, hoping their heirlooms could bring about a better future to her family.

Ren tried to persuade Xu that she should ask for money instead of the hukou in the city and a job, but Xu declined. "Money only has temporary value. Household registration and a job lasts much longer," she told him.

Liu Guanwen agreed to Xu's demand and said the deputy governor of Shanxi Province approved the household registration proposition.

After the artifacts were donated, Xu's family began to wait.

Broken promise

The promised job and change in household registration never came.

Even though Xu Huiyun and Xu Jinwei made multiple inquiries about the household registration and job, they were never given a solid response. Ren Fuxing also wrote many letters to provincial officials, hoping they could fulfill their promises and help the family resolve its household registration issue, but all were in vain.

In 1999, Xu's family sued the Shanxi Culture Research Society and its vice president Liu Guanwen, in the hope of retrieving their donations. Back then, Xu Jinwei worked as a migrant worker in Taiyuan, hauling carts loaded with stones in construction sites. Each haul earned him 30 cents.

During the investigation, investigators found many of the artifacts were stored in the office and home of Liu Guanwen. In response to the judge, Liu said he had kept them there for research purposes.

During the first hearing, the Shanxi Culture Research Society presented a letter by the Shanxi Cultural Relics Bureau, saying that after Xu's donation, the State now owned the artifacts and couldn't return them. Taiyuan's intermediate court then ruled against the Xu family. The verdict was sustained by a higher court.

Since it was impossible to retrieve the artifacts, Xu's family could only ask for compensation. But they were not able to get a fair assessment of the value of the artifacts. In 2001, the Shanxi Cultural Relics Bureau assessed the value of the 293 artifacts at 79,080 yuan. "It was a joke how little that was," Ren said.

Moreover, 28 artifacts went missing, including family portraits, an annotated copy of Book of the Later Han, and valuable handwritten scripts. When the court asked the Shanxi Culture Research Society where the missing artifacts went, they weren't able to present any documents showing their whereabouts.

The police tried to interview Liu Guanwen many times, but he was in poor health condition and wasn't able to talk. In 2007, Liu Guanwen died. The Shanxi Culture Research Society soon washed its hands of responsibility. This killed the last hope of the Xu family to retrieve their heirlooms.

Ren said the Shanxi provincial government should accept responsibility for letting the case drag on so long.

"Liu Guanwen got the approval of a deputy governor of Shanxi Province before he started to accept the artifacts. Xu's descendants also believed in Cui Zhengsheng because he was a middle person for the deputy governor and Liu," he said in a statement.

But no matter what, Xu believes it's now impossible to get his heirlooms back. In retrospect, Xu Jinwei now thinks the whole incident was a scam. "They never wanted to fulfill their promises," Xu said.

The 50-year-old farmer now lives in financial hardship and is illness-stricken, and his family is supported by his wife washing dishes in a restaurant.

Tencent and Southern Metropolis Daily

Newspaper headline: A family betrayed