Activist challenges perceptions of Chinese immigrants in US

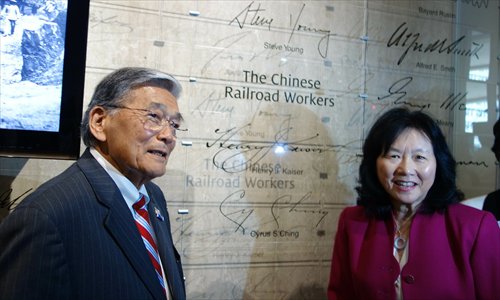

Connie Young Yu stands next to former US Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta during the ceremony that inducted Chinese Railroad Workers into the Hall of Honor, at the Department of Labor in Washington D.C. May 9, 2014. Photo: Courtesy of Connie Young Yu

Every time Connie Young Yu, 74, walks on what remains of the Transcontinental Railroad, she is moved to tears.

The 3,200-kilometer railway, built between 1863 and 1869, linked the eastern United States to the western part of the country. Over 12,000 Chinese laborers undertook this dangerous and difficult work. Around 1,200 laborers died in the process.

Those laborers were paid less than white workers, and had no legal protection. A lack of correspondence sent by these workers means that people know little about them, where they came from or what became of them.

For decades, Yu has been determined to unveil the untold stories of Chinese laborers' struggles in America.

At Stanford University's Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, one and half centuries after Chinese migrants labored on the Transcontinental Railroad, Yu and other experts shed light on their stories.

In May 2014 Chinese laborers were honored by being registered in the US Department of Labor's Hall of Honor in Washington D.C.

Yu and other activists fought for decades to see this day.

Early aspirations

Connie Young Yu was born in June 1941, six months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and lived in Whittier, California for the first six years of her life. When she was six months old, her father John C. Young left the family to fight in World War II for three and a half years. His father played an instrumental part in designing explosives used in the battle of Songshan in the China-Burma-India Theatre.

While her father was away, her grandparents helped to take care of her and were a major influence on her life. Her father felt it was his destiny to fight for the US alongside the Chinese. As a young child, Yu also felt this Chinese legacy, as her grandfather was a supporter and friend of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China.

In 1959, when she was at Mills College, a prestigious liberal arts college in California, she dreamed of writing the great American novel.

"I thought of myself then as a complete American, not as Chinese. At that time, in American society there was no interest in any cultures but white culture. It was a very monolithic society. There was lots of prejudice and discrimination," Yu told the Global Times.

She became more aware of her roots during her senior year in a seminar about Mark Twain, when she was encouraged by a professor to write her paper on Twain and his dealings with the Chinese.

Twain had been a reporter in San Francisco in the 1860s, and wrote about how upset he had been when he witnessed Chinese people being attacked on the streets while policemen just watched. Twain filed the story, but the editor said: "I can't put the story in the newspaper, it will offend our Irish readers."

When Yu wrote her paper, "Mark Twain and the Chinese," it brought back memories of discrimination against her parents and grandparents. It was only in 1943, when the US and China were allies during WWII, that the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese immigration to the US, was repealed.

Making an impact

In 1969, Yu's parents attended a ceremony marking the 100th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. In his speech, the then US Transportation Secretary John Volpe said, "Who but Americans could have blasted tunnels through the Sierras? Who but Americans could have built 10 miles of track in one day?" Yu's parents were very disappointed by what they saw as ignorant remarks.

Yu's mother suggested to Yu that she wrote about it. Yu published "The Unsung Heroes of the Golden Spikes," in the San Francisco Examiner. The article was about Chinese railroad workers, a subject familiar to Yu as her own great-grandfather had worked on the railroad. "After this article, I think I found what I wanted to do with my life. The whole idea is to be a mover and shaker in American society. To make an impact, to change the stereotypes about Chinese people. I was always an outsider. Suddenly, I became part of the process," Yu said.

At the time, the Vietnam War was raging. Yu became involved with the anti-war movement. While doing a radio program, she had many chances to interview people. It was all about getting the word out.

The fight continues

Yu writes about the Chinese, Japanese and Vietnamese immigrant experiences in the US. She has published works such as Chinatown San Jose and Profiles in Excellence: Peninsula Chinese Americans.

"I like stories and heroes. They are not heroes so much as great statesmen. They are grass-roots heroes who fought for the people. I want my kids to know about this."

She also wants people to know who the villains were.

"During the construction of the railroad, there were people that threw rocks at the Chinese workers and shouted, 'Chinese must go.' Some unions started an all-white anti-Chinese policy - the Segregationists, the KKK. We know their names, they are in the history books," she said.

Yu has interviewed the descendants of Chinese workers. Though there are no letters or diaries written by the workers to describe their experiences, Yu discovered other evidence of their struggles, such as certificates, residence permits and other documents. Her great-grandfather's certificate of residence is one such example.

"For me, it is proof of my ancestor living here. It is a paper trail of witnesses. It is a witness to our people. It is a witness to our struggle. "

For Yu, it is a struggle that has not ended.

"In America today, there is an ongoing struggle for fair wages and equal rights. Some new immigrants are suffering. America is seeing the same thing all over again. It has poor and oppressed workers. Understanding past struggles will empower each one of us," she said.

Newspaper headline: Setting the record straight