Teachers defend Chinese schools, but say lessons can be learned

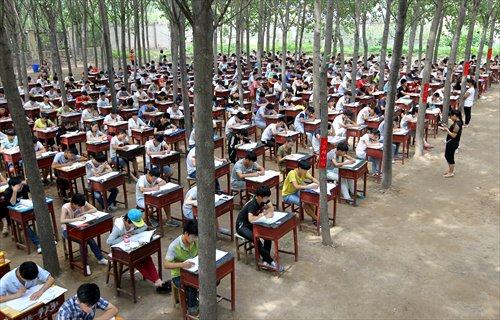

Students of a school in Xinxiang, Henan Province take a test in a forest on July 3 so that teachers can monitor them and the environment may be more relaxing than classrooms. Photo: CFP

Two Chinese teachers who were featured in the controversial BBC documentary Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School have again stirred up discussion, after they complained that the show didn't reflect reality and one of them called schools in both countries "testing factories."

The comments made by Yang Jun, a Chinese teacher who has taught for decades in China and Britain, followed a piece written by Guardian commentator Simon Jenkins in which he described Chinese schools as "testing factories."

"Grades are everything, and the core of UK education is no different to a 'testing factory,'" Yang Jun told the Xinhua News Agency on Monday.

"Schools will not renew contracts with teachers if a student performs badly in their A-levels or General Certificates of Secondary Education (exams UK students take at 16)," added Yang.

'Unrealistic' experiment

The show had five Chinese teachers heading to Bohunt School in Hampshire to teach 50 teenagers for four weeks. The classes followed "traditional Chinese teaching methods," starting at 7 am and finishing at 7 pm and included flag-raising ceremonies, morning exercises and extended evening self-study sessions.

"What is shown in the documentary isn't the whole picture," said Li Aiyun, a teacher from Nanjing Foreign Language School who participated in the BBC project, saying she told the show's producer many times that such "traditional methods" are not used in top Chinese high schools nowadays.

She added that her school, in East China's Jiangsu Province closes at 4 pm and class sizes are generally smaller, unlike the 50-pupil classes shown in the film.

"Actually the education in different areas in China varies hugely, and none of the five teachers are from so-called 'traditional schools,' and in no way could they represent the whole picture of Chinese education," said Li, People's Daily reported Wednesday.

As a TV program, the documentary must primarily attract audience attention rather than providing an academic exploration of Chinese education, Chu Zhaohui, a researcher at the China National Institute for Educational Research, told the Global Times.

However, Sam Bagnall, executive producer of the program and creative director of BBC Current Affairs Television, emphasized that the comparison made in the film was fair in an interview with the Chinese-language branch of BBC in August.

The Chinese education presented in the film is "typical" and "traditional," and "hardworking" is a common stereotype of Chinese students, said Sam.

Making notes

China should have a clear understanding of its education system, where it is now and where it is heading to, Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute told the Global Times.

A critical perspective of education is needed, said Yang. "The Chinese spirit of hard work and respect for knowledge, teachers and the elderly should be taught, and also the wide range of knowledge and social skills of UK students."

"The [test factory] comparison of Chinese education and UK education is groundless, each of the two countries has good and bad players in the education sector and each school itself has its advantages and shortcomings," Wang Daji, a retired teacher from Chen Jinglun Middle School in Beijing, told the Global Times.

Wang, responding to criticism that Chinese students are unhappy and burdened with stress, said that the definition of "happiness" must be clarified, as the happiness one feels from joking and playing is different from the happiness that one feels after achieving something through hard work. "Learning is a happy process, and the pursuit of grades does not contradict with personal growth," added Wang.

The conclusion that Chinese teachers are too harsh on their students and the teaching approach lacks flexibility and shows an insufficient knowledge of education in China, said Chu.

Chu said many high school teachers he knows "respect pupils' individual natures and encourage diversity," but that their ideas are held back by the reality of strict teacher evaluations and parents' demand for high grades.

Li said she hopes to introduce UK teaching methods to China, such as respect for individual differences, and schooling that encourages confidence and critical thinking.

"There is no perfect teaching approach. Both 'student centered' and 'teacher led' teaching styles are effective if applied at the right time to the right group," wrote Yang in her article.

Newspaper headline: Just testing factories?