Returning doctor explores field of head transplants

Ren performs surgery on a pig. Photo: Courtesy of Ren Xiaoping

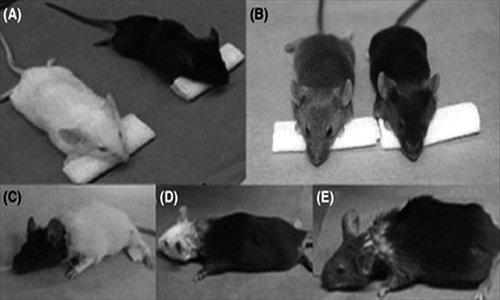

White, black and brown mice before and after head transplants. Photo: Courtesy of Ren Xiaoping

Ren Xiaoping. Photo: Courtesy of Ren Xiaoping

Ren Xiaoping, sitting in his office in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, in Heilongjiang Province, handed out advice as he checked a patient with a slipped disc. Talking with an accent typical of Northeastern China, he then told her the location of the hospital pharmacy and sent her on her way.

The patient probably didn't know that her doctor, apart from offering consultation to patients on normal bone and spinal injuries, harbored an ambitious plan - to transplant human heads. Since 2013, at his lab in the Harbin Medical University, the 53-year-old Harbin native and his team of around 20 have already conducted hundreds of hours-long head transplants, using over 1,000 mice, in an effort to find ways to prolong their lives after they awoke from surgery.

The Chinese-American doctor, who went to the US about 20 years ago, returned to China in 2012, attracted by China's rapid science development, its eagerness to prove itself in the most cutting-edge fields of science and technology and its generous funding for medical research.

When the mice wake up, they breathe normally, blink and move their whiskers, Ren wrote in a research paper published in the journal CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, which also includes photos of a mouse with a white body and a black head, and a black mouse with a white head. Ren said some of the mice only live for three hours after the head transplant, while others live for up to one day.

Unexpected fame

Ren became famous worldwide earlier this year, after Italian surgeon Sergio Canavero announced plans to work with him on the world's first human head transplant in as early as 2017. Ren later clarified that transplanting human heads is not yet on his timetable, although the two scientists are collaborating and sharing research.

Their unorthodox research focus, however, soon grabbed the attention of the media and academia. Some media dug out Ren's mice experiments and called him the modern Frankenstein, and some experts slammed the feasibility and morality of the transplant. Netizens discussed heatedly what would happen if a man is given a woman's body, or if their child will inherit the body donor's genes.

Ren admits the intricacy and complexity of the operation. While most transplants only concern organs, head transplants - or, in effect, body transplants - involve multiple organs and the spinal cord, the large bundle of nervous tissues that connect the brain and the spine. Whether one person's spinal cord will be compatible with another's is still a difficult problem yet to be solved in modern science. Other difficulties include whether cells in an amputated brain can survive the long surgery.

But Ren is confident that he can crack these hard nuts one by one, and that his research will eventually benefit mankind as a whole. "For people who are affected with incurable, fatal diseases, the possibility of a head transplant offers them the hope to survive," he said. He added that 10 volunteers, who are mostly paralyzed or suffering from severe illnesses, have already approached him, expressing their willingness to have the transplant when it is ready for human testing.

While some experts estimate that human beings are still decades, or even centuries away from head transplants, Ren said he wants to make it a reality much sooner than that. "I want to speed up the experiments. After all, the purpose of medical science lies in application - if the research doesn't have practical use, it's meaningless." he said.

Returning to China

In 1996, Ren, aged 33 at the time, was already the vice director of the orthopedic department at the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, focusing on the reattachment and reconstruction of amputated fingers or arms. "In many cases, the amputated arms of patients are so badly injured that they can't be reattached. Naturally I started to pursue research in limb transplantation," he told the Global Times.

Young and promising, the university sent him to train in the University of Louisville in Kentucky, US which had a history of training and working with Chinese doctors. During his five years of research there, Ren helped create a feasibility model of large animal limb transplantation to allow the modulation of immune-system reactions. In 1999, doctors in Louisville performed the first hand transplant in the US, partially based on Ren's research. That experience put Ren at the frontier of medical development, and his income soon grew from $2,100 a month to over $4,000.

The rest of his story is typical of Chinese scholars who were sent to the US in the 1980s and the 1990s in an effort to speed up the country's development in science and technology. Ren didn't return to China as promised, and stayed in the US where he pursued his research interests. "Twenty years ago, most Chinese people who went to the US would be surprised at the infrastructure and quality of life there. The research environment was also much better," Ren recalled.

In 2004, after eight years in the US, he obtained US citizenship, a choice which he said mostly owed to his older daughter, who was applying for medical school at the time and needed citizenship to secure scholarships and other opportunities. Ren dismissed it as a decision that wasn't of much importance. "It actually brought me lots of trouble. Also, getting US citizenship doesn't mean I'm not Chinese. People can always change their citizenship, but inside I always think of myself as Chinese," he said.

In 2012, Ren returned to China alone, leaving his wife and daughters in the US. Harbin Medical University promised 10 million yuan for his research. He has also secured funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and another local foundation.

"Whether a country's national government is willing to offer funding and support is critical to the progress of the experiment. In the US, it would be far more difficult to get funding for research so specific and sensitive as this," he said.

Ren said his next step would be doing head transplants on monkeys, but has not yet fixed a timetable for this surgery.

Newspaper headline: On the cutting edge