HOME >> OP-ED

Models best placed to defend their own health

By James Palmer Source:Global Times Published: 2015-12-28 0:43:01

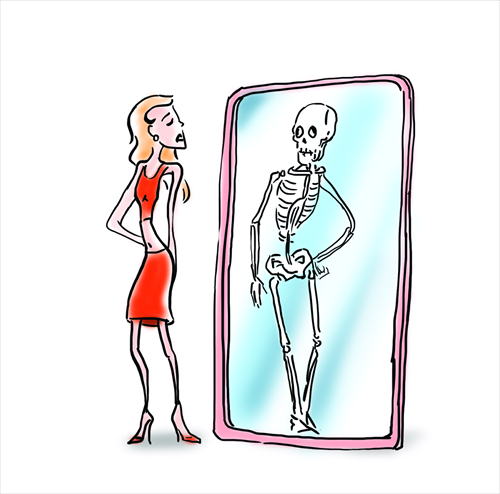

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

French models are famously skinny, but that might not survive a new law, passed last week, that forbids brands or agencies from using models with a Body Mass Index of below 18, classified as "underweight." The French fashion industry is up in arms, but it should recognize that it's the industry's own failings that created the demand for the law.Eating disorders are a major problem within the modeling world. The pressure to stay skinny and match a distorted view of what a woman's body "should" be is intense, and models are young, vulnerable, and far away from home. This is coupled with "advice" from the older men who dominate the industry that is often outright abusive. Former model Ainsley DeWitt records being told by a director to eat nothing and drink only water for two weeks, when she was at a weight that would have already had doctors worried. Kirstie Clements, an ex-Vogue editor, describes hearing a Russian model say "It is my job not to eat" - one of the few sentences she could speak in English.

Many models target diets of below 1,000 calories a day, a dangerously low level that can permanently damage health. In research, models score significantly higher than control groups on indexes for signs of eating disorders. The industry has done little to tackle the problem, and the average size of models appears to be shrinking each year. It's almost as if the middle-aged men who run the industry want to have a pool of psychologically and physically weakened women, many of them still teenagers, to draw on - or, some might say, prey on. The effects of this go beyond modeling. The average US model is thinner than 98 percent of American women; the prevalence of stick-figure models in media images helps fuel an environment in which eating disorders have reached worrying new heights, especially with the Internet. In China, such images add an extra burden to young women who are already under intense social and, often, parental pressure to "control" their weight.

We might, therefore, welcome the French move. It's one that Chinese lawmakers could imitate. But it seems to be to have severe problems. How is the women's weight going to be monitored? Is the blame going to end up being put on women themselves? Are models going to be forced into a pattern where they have to keep just the right weight, above an arbitrary line but with their bodies still distorted enough to please their patrons? What about the many women for whom a BMI of 18 is natural? Why are we putting so much trust in BMI, a much-criticized and, ironically, one-size-fits-all measurement?

And in an internationalized world like modeling, a national law may not do much. French magazines may end up simply hiring models in the rest of Europe. We see that situation already in China, where any attempt to regulate modeling would have to first begin with clearing up the industry and revising visa laws. The vast bulk of models in China are not working legally, not least because China provides no visa path for foreigners to work as freelance contractors. Instead they're being brought in on temporary visas, often with the collusion of large agencies both in China and abroad, and left legally and financially vulnerable.

Promoting healthier models needs to begin with cleaning up the modeling industry itself. The best place to start may not be with the agencies, but with the magazines and other media that use them. Pressuring media to adopt codes of conduct about ethical modeling that begins to crack down on the prevalent sleaze inside the industry would help to bring it under control. Vogue and some others have already pledged not to use models under 16.

Unionization would also be a powerful weapon. Models are vulnerable because they're short-term contractors whose fortunes rise and fall with casting directors. Actors used to be in a similar position, before Equity and other unions emerged in the 1920s to help defend their rights. Equity UK has already opened up to models and successfully negotiated agreements to protect their rights; the more models are represented collectively, the more the industry will have to take into account their wellbeing, or pay the price.

The author is an editor at the Global Times. jamespalmer@globaltimes.com.cn

Posted in: Viewpoint