Byzantine red tape holds up Sino-Indian ties

Illustration: Shen Lan/GT

The world is becoming a global village in which people are traveling beyond borders like never before. However, the bilateral exchanges between India and China have long been small compared to the size of the two countries, which together account for more than a third of the world's total population. According to an Indian official, in 2013 only 680,000 Indian nationals went to China, which even less Chinese of just 175,000 made the reverse journey. These numbers could hardly reflect the increasing political and economic importance attached to the relations between the Asian giants.

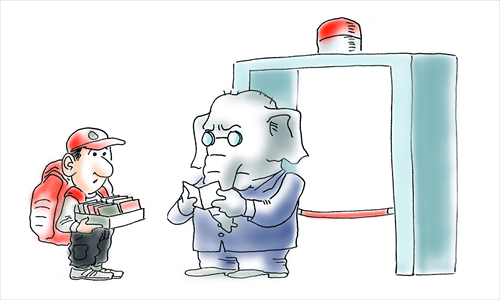

Among other things, India's Byzantine visa regime as well as its cumbersome and delayed procedures are a major challenge for foreign tourists. As a result, India only saw 6.5 million tourists in 2012 despite its amazing landscape, enormous population and vast territory, whereas tiny Dubai, with a fraction of the landmass and people of India, attracted more than double that amount every year.

When it comes to China, India's diplomatic distrust results from the border warfare back in the 1960s and the lingering disputes add an extra layer of complicity. This has rendered China a particular target for the recalcitrant Indian officials. For example, India's security establishments were explicitly against extending a more accessible visa to Chinese citizens, fearing the latter's "espionage" and "visa misuses" might compromise India's security.

Fortunately, Prime Minister Narendra Modi overruled these objections and announced a trailblazing visa scheme for Chinese tourists in May 2015, streamlining the process with online application and quick authorization. This move has brought new dynamics to the bilateral relations almost immediately. For example, tourist arrived in India on e-visa increased from a mere 2,705 during October 2014 to 56,477 in October 2015, registering an astonishing growth of 1,950.9 percent. Among more than 100 countries eligible for India's e-tourist visas, China was one of the top 10 contributors, accounting for almost 3 percent of this incredible four-digital growth.

The new tourist visa scheme has made impressive inroads, but the Sino-Indian visa regime was still far away from ideal. Chinese nationals' conference and business visas to India, for example, still feature overcautious arrangements and rampant procrastination.

As these visas required approval from India's Ministry of Home Affairs on a case-by-case basis, the process has been largely ambiguous and subject to hidden and arbitrary rules. Besides virtually endless checklists of supporting documents, Chinese scholars and businessmen often have to wait for a very long period of time and, if fortunate enough, get their visa only shortly before the intended date of departure. Many of them are simply not lucky enough to have their visas approved and miss the business or academic event all together.

The burdensome procedures and seemingly arbitrary nature of India's visa regime have become a visible bottleneck for the two to widen their cooperation and interaction. As China puts forward its "One Belt, One Road" initiative, regional and country studies have gained great popularity in top Chinese universities. However, when it comes to Indian as well as South Asian studies, these universities are very reluctant, because many of them had undergone great frustrations in forming partnerships with their Indian counterparts or sending their scholars and students there.

For instance, in the academic conference of Kumarajiva 2011 held in Delhi, only half of the Chinese scholars invited were lucky enough to eventually be present, whereas the other half were either denied academic visas or delayed.

In the same vein, tired of applying for business visas, many Chinese businessmen simply use tourist visas instead. However convenient it may be, this kind of practice often deprives these businessmen of the legal protections they should be entitled to. As New Delhi pursues the ambitious "Make In India" strategy while China is in a position to move its world-class production capacities abroad, India's intransigent visa bureaucracy may backfire badly as it hurts itself more than it bothers China.

Every cloud has a silver lining. As a series of recent events have played out, India's visa regime vis-à-vis China may once again undergo major transformation. India's intelligence agencies and security establishment have long been hardliners on the issue. However, even they seemed to loosen their footing at the end of the day.

In November 2015, Rajnath Singh became India's first union home minister to visit China in a decade. After he met Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and the Minister of Public Security, Guo Shengkun, both sides agreed to form a ministerial-level conference mechanism to gear up interaction concerning the security-related fields.

While boundary disputes and the historical episode demand careful management and are unlikely to be solved shortly, it is wise for both capitals to look beyond and explore the new possibilities. Just as Modi braved objections to free up e-tourist visa for Chinese nationals, it also takes courage to break the time-honored intransigence of the security establishment. With both Asia giants determined to deepen the security cooperation, a more user-friendly visa regime is actually the low hanging fruit. After all, visa rules should be reflective of changing political and economic realities.

The author is a visiting scholar at Tsinghua University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn