Chinese students in US get first taste of demonstrations

Nervous protesters

As Chinese-Americans across the US protest the manslaughter conviction of NYPD officer Peter Liang, Chinese students in the US have been conspicuously absent from the demonstrations. Some expressed concerns about a political form they've never come across, while many are indifferent about social issues and American politics.

Protesters hold a rally in support of former NYPD officer Peter Liang in Brooklyn, New York City, February 20. Photo: CFP

Ann never really paid any attention to demonstrations prior to going abroad to the US. Her parents specifically told her to stay away from political gatherings.

But last Saturday, the 28-year-old Chinese PhD student in Boston took part in demonstrations that swept across the US to defend Peter Liang, the Chinese-American New York police officer who has been in the center of attention and heated debates for the past few weeks.

Rookie cop Liang was convicted of manslaughter and official misconduct on February 11 over the 2014 death of Akai Gurley. The unarmed black man was struck in the chest by a bullet accidentally discharged by Liang when the officer was spooked by a noise while patrolling the unlit stairway of a public housing building in Brooklyn. Liang faces up to 15 years behind bars.

At first Ann was worried that the demonstration would be chaotic or even dangerous, but she found that it was peaceful and the protesters were calm. The organizers had applied for a permit and the demonstration was limited to a park.

There were no conflicts at all, the police were friendly, and from octogenarians to toddlers, everybody walked in an orderly manner while shouting slogans.

While being part of the event was an eye-opener for Ann, she was one of only a few Chinese students who took part in the demonstrations. Most still shy away from these activities - some worry about the safety of protests, while others are disinterested in the internal affairs of a foreign country.

Calling for justice

Wang Tian is proud of the fact that his words were read by over 10,000 people in the US in just four hours.

The Los Angeles-based organizer of protests against Jimmy Kimmel Live! and ABC in 2013 over comments he felt were prejudiced against Chinese said he read about Liang and immediately sent out a WeChat public message to call for demonstrations.

Within a few minutes, he received phone calls from many friends that he met during the 2013 demonstrations. Within hours, people started chat groups and talked about organizing demonstrations in 15 cities. The protests quickly consumed all his free time, as he received more than 9,000 new messages in a matter of hours.

Wang has long been active in organizing demonstrations in the US. He said it was due to his childhood experiences that he insists on fighting discrimination and "pursuing justice and equality."

Wang Tian left China in 1994, when he was 10 years old. He first migrated to Singapore, then Australia, then the US. He said he was regularly bullied because of his race.

When Wang migrated to the US he felt liberated. He says in the US, people can express their discontent, but are bound by law to refrain from violence. He's gradually grown to appreciate demonstrations as a way to voice his concerns and pursue justice.

Orderly parades

No exact data was available at this point, but Wang estimated 100,000 people participated in demonstrations nationwide.

According to media observers, most of the people who participated were mobilized by associations for Chinese-Americans that are organized according to which of China's provinces they or their forefathers came from and local Asian-American chambers of commerce, but few Chinese students were involved partly because they weren't reached by these groups.

Ann was one of the few students who took part in a demonstration in Boston. She secretly went to the protest without telling her parents, who had specifically warned her against attending this sort of event long before she went to the US.

"I was afraid I might freak out my parents if they had known I took part in this," she said. "They specifically said I shouldn't follow others into political activities on the streets, even before I went to Beijing for college."

Ann said if she had recently arrived in the US, she may not have had the courage to join this demonstration either. But after living in the US for about three years, and feels she has a more nuanced understanding of the social environment and feels quite secure.

She read about Liang's case on social media and was touched when she saw Liang bow his head in despair as the verdict was announced. She felt sympathetic towards Liang, but didn't know what she could do.

A few days later, she read on Facebook there will be a demonstration in Boston Park and joined the chat group. The next day, she found herself protesting with 2,000 other people and felt overwhelmed.

"It was an interesting experience," she said. "Under the American social system, there's a channel for the general public to voice their concerns. It doesn't create chaos, but instead, it releases anger and resentment."

The demonstrations taught Ann about American society. She saw the protestors as fighting for equal rights for all minorities in the US. She also feels she has a better understanding of how Asians can fight for more political power and status in the US.

Her words are echoed by Cindy Lin, a PhD student in Philadelphia.

Like Ann, Lin felt the demonstrations were orderly and well-organized. Participants made flyers they would distribute to people along the streets and explain the protest to them. As a result, many people came up to ask what's going on and some joined in along the way.

But very few participants were Chinese students, Lin said. Most people were older immigrants. Ann expressed similar observations.

"This concerns their rights more," Ann said. "If you regard yourself as an American citizen, of course you'd care more about America's social issues and rights."

Playing by the rules

Wang admits in the past protests he's organized that he's only seen few Chinese students getting involved. Most of the participants were people who have been in the US for more than five years, who understand how things work.

He believes because many students have just come to the US and experienced little or no discrimination, not like the abuse Chinese communities have suffered in the past, so they don't understand why people march on the streets for a "small matter."

Besides, some are not familiar with how demonstrations work and might be afraid.

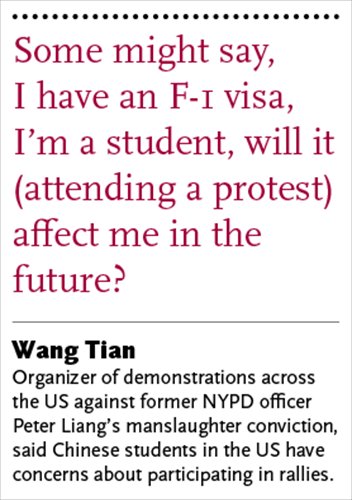

"Some might say, I have an F-1 visa, I'm a student, will it (attending a protest) affect me in the future?" he said. "But they don't understand, it's a common thing in the US and anybody can participate, as long as you don't break the law."

Another reason may be varying views of whether "Chinese" constitutes a race or a nationality. Liu Weidong, an expert on American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times in an earlier interview that first-generation Chinese in the US often feel a strong bond with the term "Chinese," but this often weakens over the course of a few generations.

Liu said that while the Chinese government and academia often use the term "Chinese" to refer to people of Chinese descent all over the world, the Chinese public often sees foreign-born Chinese as foreigners.

On the other hand, many Chinese students see themselves as guests in another country, and doesn't think these racial issues matter to their personal rights.

In the comment section of an article on Liang's case published prior to the demonstrations in the North America Student Daily, a social media news portal, some expressed disagreement. Some Chinese students showed that they do not link themselves closely to the Asian-American community.

"I think the reason Chinese students aren't participating is that Chinese-Americans discriminate against us the most," one comment read.

"I think this demonstration for Liang is a matter of the Chinese fighting for the right of an American," another read.

Fang Liang (pseudonym), a mechanical engineering PhD student at Princeton University, has been in the US for nine years. In his experience, students who have only been in the US for a couple of years generally don't care about American politics or social issues.

People like him, who have American friends and want to stay in the US in the long term, are more likely to see these matters become as important. This year, he has closely followed the presidential campaign, and can fluently debate with his American friends about the candidates.

When the demonstrations happened, he was out of town. Otherwise, he would've definitely taken part in them.

"If you want to actively participate in their society, you should play by their rules," he said.

Newspaper headline: Joining Asian-Americans, Chinese students in US get first taste of demonstrations