Grown-up children of migrant workers more likely to be jailed

As millions of migrant workers travel to find jobs in cities around China, a great number of children have been left in their rural homes without the proper parenting they urgently need. This has resulted in a significantly higher crime rate among these children when they grow up. Worryingly, this problem is being passed to the next generation, as left-behind children leave their own children behind.

A prison for juveniles is seen behind barbed wire in Fuzhou, Fujian Province. Photo: CFP

Dressed in a blue prison uniform with a conspicuous armband around his left arm which indicates that he is under "strict supervision," Deng Hui (pseudonym) doesn't look like he wants to make friends.

Most of the time he is quiet but whenever he feels a little offended, Deng's guard will immediately fly up and he will prepare to fight.

A few months ago, Deng beat his team leader with a brick after the man criticized him. He was placed under strict supervision after this act of revenge.

Before being locked up, Deng was a member of a motorcycle gang who robbed people on the streets.

Deng is just one of many former left-behind children - whose parents left them with relatives to seek work in cities - who have gotten in trouble with the law.

While inside prison, Deng's identity as one of the first-generation left-behind children has drawn interest from experts.

"The number of migrant workers in prison who were once left-behind children is about 20 percent higher than the number of non-left-behind migrant workers in prison," said Zhang Dandan, an assistant professor at the National School of Development of Peking University, in a Phoenix Weekly magazine report.

As more and more reports concerning left-behind children's high rate of incarceration have been published in recent years, Zhang decided to spend two years researching and interviewing jailed former left-behind children.

Their childhood experiences have had a serious long-term influence on these prisoners, who often display violent tendencies, emotional instability and the feeling that they have been treated unfairly, according to Zhang.

This problem is cyclical, with an invisible intergenerational succession underway that is passing these problems onto their left-behind children.

Liu Xinyu, founder of On the Road to School, an NGO which provides financial and psychological help to left-behind children, told the Global Times that "Now the government's and society's support for left-behind children is concentrated in offering them financial support, like buying schoolbags for them.

However, this is the wrong direction. The psychological problems those children have is the more urgent problem."

Underage inmates stand behind bars. Photo: CFP

Shadow of an unhappy childhood

"My father died half a year after I was born. My grandparents did not tell me the reason for his death," Deng told the Phoenix Weekly.

But according to prison guards, Deng's father was imprisoned when he was 2 years old and later escaped and disappeared.

Throughout his childhood, he never got the chance to communicate with his parents, and had to depend on his grandparents.

This insecurity has shaped his character. "I can't get along with other prisoners. I'm introverted and easily angered," he admitted.

Some 51 percent of Zhang's interviewees in jail reported that they resent that their parents didn't look after them during their childhood.

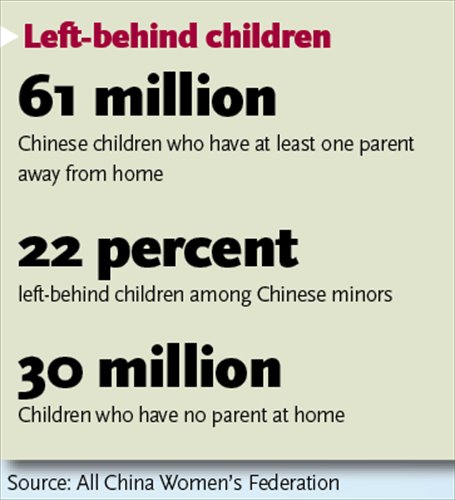

Statistics from the All China Women's Federation showed that currently there are 61 million children in China who have at least one parent away from home, accounting for 22 percent of all the country's minors. About 30 million children have no parent at home.

Liu told the Global Times that based on their survey of left-behind children, they estimated that about 10 million such children don't see their parents all year round, and 2.6 million don't even receive a single annual phone call from their parents.

"They are literally orphans in soul. They are unable to get emotional nourishment from their parents," said Liu.

A study by the Shandong Academy of Social Sciences in 2010 revealed that left-behind children are 11 percent more likely to commit crimes than children whose parents live with them.

"Some students leave school before they finish their compulsory education and without a good education and guidance from adult guardians, these children go the wrong way," Xiao Hui (pseudonym), a teacher in a primary school in Liupanshui, Southwest China's Guizhou Province said in a previous Global Times report.

"The crime rate among left-behind children is high. Some children began by stealing around their villages and some end up doing more serious crimes, like murder," she said.

In Zhang Dandan's research, robbery and intentional injury were the most common crimes committed by the young prisoners.

Lasting scar

From October to December 2014, On the Road to School surveyed 3,000 left-behind children across China about their psychological condition. The survey revealed that some 70 percent of them have psychological problems of varying severity.

Data from the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences showed that about 34 percent of left-behind children have suicidal tendencies. Among them, 9.7 percent have attempted to commit suicide.

"This shows that they don't care about their own life, so they are more likely to treat other people in the same way. So many of them go on the criminal road," said Liu.

On June 9, 2015, four left-behind children in Bijie, Guizhou drank a bottle of pesticide and died at home.

"I vow to die before I'm 15 years old. Death has been my dream for years and now, I want my life to return to zero," read the suicide note of the 13-year-old, the oldest of the four.

When Liu and his team talked with left-behind children about what they dream of being in the future, most of them said they did not harbor a dream. "They did not know the meaning of their lives and felt a great sense of inferiority," he said.

In Zhang's research, after these people are put behind bars, psychological intervention had little effect.

"What they have lost during childhood and the psychological damage they received are hard to cure," explained Liu.

Once, two college students majoring in psychology that were left-behind children told Liu that even though they tried to use psychological methods to combat their childhood trauma, they were still unable to truly recover from it.

Although most criminals can talk about their experiences and are able to reflect on how they shaped the people they are today following compulsory psychological treatment, many still refuse to admit their criminal guilt.

Deng still denies his involvement in robbery. "They needed to find a scapegoat," Deng said.

According to the police, Deng was not only actively involved in robbery but also got two women involved in the gang.

Yao Yiqiu, a migrant worker and one of the first-generation left-behind children, used a knife to threaten his victim during a burglary but claimed that he was just "offering a hand." Wu Jinsen, who abducted women and forced them into sex work overseas, still thinks he "was just playing for fun."

The prison officers said that on many occasions, even after these people get released, they soon end up back in jail.

Passing problems on

Recently, Deng received a letter from his grandparents, asking him for money to cover his 8-year-old son's tuition fees.

The couple are in their 70s and don't have much income.

"I don't have money, so just don't let the kid go to school," he replied in the letter.

This is what prison psychologists are concerned with most. When these prisoners go into prison, they leave their children behind, passing on the psychological problems that helped land them in prison in the first place.

A prison guard said that he thinks that China is only seeing the tip of the iceberg now. As people started to leave their hometowns for work in around 1996, now most left-behind children are under 20.

"When they grow up and enter society, it will be a very worrisome issue," the officer said.

In Zhang Dandan's survey, most of her interviewees were born between 1975 and the early 1990s. During this period, just 9 percent of minors nationally were left-behind children. When she surveyed nine provinces in 2011, 43 percent of children had been left behind.

To combat these problems, China's State Council released guidelines on the protection of left-behind children in February.

It states that government and village committees should know the situation of left-behind children and ensure that they are properly taken care of. A heavy emphasis is also put on parent's primary responsibilities.

Governments can cooperate with charities and voluntary bodies to provide services, and a system of reporting, intervention, assessment and aid will be established, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

To Liu, this is a step in the right direction but is not far-reaching enough. "The road is difficult as so far there is no comprehensive way to thoroughly solve their problems," he said.

On the Road to School's program now covers 64 schools in 18 provinces and has reached more than 27,000 children. "It does bring some positive changes to left-behind children. But this is not enough."

"What we aim for is to develop a system that can be replicated by others that can help the left-behind children at a fundamental level," he noted.

Phoenix Weekly contributed to this story

Newspaper headline: Left behind bars