HOME >> OP-ED

Without tackling caste, India will stay stuck

By Ding Gang Source:Global Times Published: 2016-3-2 23:28:01

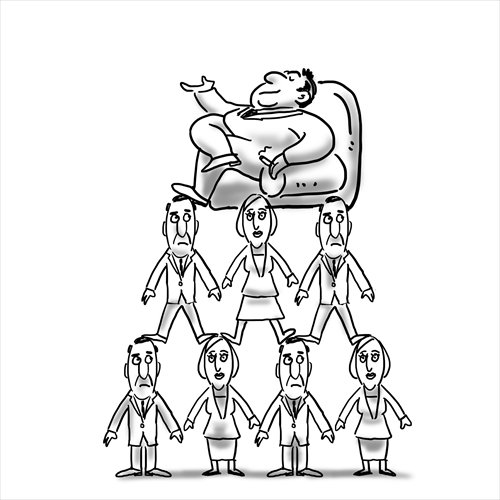

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Violent protests flared across the northern Indian state of Haryana late last month. The Indian government's move to grant public sector job quotas to more lower caste groups bred vehement discontent among the Jats, who are currently listed as an upper caste.

Similar riots have been seen before. Back in 2007, the Indian government planned to offer more education and employment opportunities to young people from lower castes, which, however, encountered strong protests from upper caste students and other social forces that reeled the country for more than 20 days.

The lower castes, most of whom are peasants, account for approximately 16 percent of India's total population. Whether they can gain equal status determines whether the nation will ultimately narrow its staggering wealth gap and eliminate urban-rural disparity.

India's caste system is claimed to be 3,000 years old and was officially abolished in 1947 when India gained independence. Since then, caste-related classification and discrimination have been viewed as illegal practices. The Constitution of India articulately stipulates, "The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them."

Nonetheless, the caste system still has tenacious vitality across Indian society. Each caste is a closed group of vested interests and there's a chasm between upper and lower castes. For instance, there's little chance for lower caste citizens living in rural areas becoming urban dwellers alongside upper castes.

Solving this conundrum inevitably needs more investment, especially in poverty-stricken villages. The Indian government should also adopt more forceful policies. Besides, other castes need to sacrifice their interests to some extent, which is the most difficult thing to do.

If the estrangement among various castes could not be broken or their differences fail to be removed, no investment will help promote equality.

Any help given to lower castes will sow strong dissatisfaction among the upper castes. But if the government averages its investment to all castes, it will undoubtedly deepen the rupture among them.

Another feature of the caste system in India is that it not only constitutes a cause of rigid social stratification and urban-rural gap, but also a reason to maintain social stability, because it cultivates the "nature" of lower castes to stay timid, complacent and to come to terms with their poverty.

However, India's social stability is established at the cost of inequality and restricts social mobility between different castes. Democracy is not a panacea to resolve this conundrum. Instead, the democratic system doesn't help dispel the rifts among different castes in practices, but reinforces their separation.

US economist and socialist Mancur Lloyd Olson, Jr. coined a concept called "distributive coalition" in his 1982 work The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities.

According to Olson, democratic institutions must spawn groups of vested interests. Through years of power accumulation, they will grow to be distributive coalitions, which will consolidate and defend their own interests via democracy.

The same principle applies to India's caste system. Every caste has its fixed social position. In particular, upper castes protect their own interests at all costs and even manipulate the political system to maintain their social status at the expense of the interests of lower castes.

Olson holds the pessimistic opinion that democracy cannot solve this issue; only revolution and external shock can break the deadlock.

India is not the sole country confronted with this intractable problem. Stratification of groups of vested interests is a common phenomenon across the diverse world. The reinforcement of distributive coalition tends to cause more social instability and even smother development in developing countries, which are suffering from colossal urban-rural gaps and overwhelming social welfare inequality.

The author is a senior editor with People's Daily. dinggang@globaltimes.com.cn. Follow him on Twitter at @dinggangchina

Posted in: Ding Gang, Viewpoint