Islamic food, water, toilet paper cause concern about extremism

Chinese Muslims have been calling on the central authorities to legislate on halal food to ensure the quality and authenticity of such products. However, regardless of whether such legislation can be passed within the legal structure of a secular communist country, some argue that unified standards for halal food do not exist due to different culinary traditions of China's several majority-Muslim ethnic groups.

A woman prepares food in a Muslim food store in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province. Photo :IC

Earlier in May, a crowd of Muslims staged a protest in front of the government headquarters in Luoyang, Central China's Henan Province, over what they say is disorder in the administration of halal food.

Pictures posted online show police officers standing in formation in front of the government building facing men wearing taqiyah skullcaps and women in hijabs.

In a separate case, Muslims in Wenzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province, forced a Middle Eastern-style kebab stall owner to apologize for selling non-halal food.

They complain there are no national rules regulating halal food production and distribution, and that regional regulations haven't been strictly enforced either where there are such regulations.

The controversy about how legislation can ensure the authenticity of halal food has been decades in the making, but has been prominent for just over 10 years.

The push for legislation on halal food has faced opposition from some segments of society and the government, as people fear that giving a legal framework for halal food would be a slippery slope to more Islamic rituals seeping into secular laws. They argue the government should stay out of religious affairs.

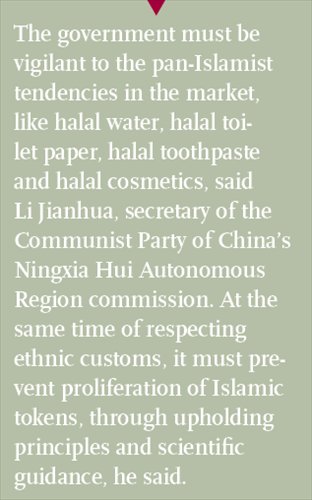

As a result of the opposition, this year for the first time the "Halal Food Management Ordinance" was not mentioned in the annual State Council Legislation Work Report which is published after the two sessions. From 2007 to 2015, the legislation was in the "Under research" category of the work report.

Halal is a term used to describe any activity or object which is permissible for Muslims to engage in or use. The rules surrounding halal food go far beyond not eating pork, also covering methods of slaughter and food preparation.

The government must be vigilant to the pan-Islamist tendencies in the market, like halal water, halal toilet paper, halal toothpaste and halal cosmetics, said Li Jianhua, secretary of the Communist Party of China's Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region commission during a religious works meeting in April. At the same time of respecting ethnic customs, it must prevent proliferation of Islamic tokens, through upholding principles and scientific guidance, he said, thepaper.cn reported.

China has a Muslim population of more than 23 million, mostly living in the country's north and northwest.

In recent years, among China's many food scandals, stories of so-called halal restaurants and food companies selling non-halal food have been common, such as using pork products in their desserts. It was discovered in 2011 that businesses in Anhui, Jiangxi and Fujian provinces were using an additive to make cheap pork look and taste like more expensive beef and selling the disguised swine as halal.

At present, only several provincial-level administrations like the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Shanghai have issued halal food production regulations, though many Muslims have complained that even in these regions the rules have been loosely enforced.

Besides food safety concerns, advocates of legislation cite the potential profits if China's halal food industry was able to compete globally. Internationally-recognized halal food standards are a prerequisite for this growth. Analysts say the global halal food market will grow to be worth $1.6 trillion in coming years, and Chinese enterprises should seize a share, especially at a time when China is seeking to strengthen its ties with Muslim countries under President Xi Jinping's strategic vision.

However, China's food safety scandals that continuously grab media attention have undoubtedly obstructed the path of halal food internationalization.

Professors Ma Yuxiang and Ma Zhipeng with the Northwest University of Nationalities, published an article in 2014 in China Hui Studies, suggesting the country make counterfeiting halal food a crime punishable by death. They also suggested that halal food enterprises should have at least 40 percent of their workforce be Muslim.

However, such suggestions have fed concerns and criticism over the State interfering in religious affairs. Critics say halal food legislation is in essence using the secular Communist administration for religious purposes, which would give religious organizations and practitioners de facto law-enforcement power.

On the other hand, many of the law's supporters view this issue from the perspective of ethnic unity. Chinese Muslims predominantly come from ethnic minorities like the Hui, Uyghur and Kazakh peoples, and often ethnic issues are intertwined with religious issues. Legislation on halal food is expected to boost unity with these ethnic groups.

"A Muslim can choose halal food according to the ingredients. But if someone demands food be transported separately, says they can't eat together with non-Muslims or demands specialized restaurants, this would be pressing against non-Muslims and an act of extremism," a netizen commented online.

Muslims debate

Responding to the debate, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission (SEAC) held a symposium in March and invited legal and religious experts to discuss halal food law. But Xi Wuyi, an expert on Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said since any new law will affect the rights and interest of all citizens, authorities should not make a decision based only on the thoughts of Muslim experts and those who support the law.

Some of those who object to the legislation are Muslims. A Uyghur commentator, who goes by the moniker "Mysterious Cabbage" on Weibo, said he believes the lack of consensus about halal food in the Muslim community means such a law will be impossible to pass and implement.

There are at least 10 Muslim-majority ethnic groups in China, but their different lifestyles and sects have led to distinct eating habits. For example, some ethnic groups eat horse meat, while others don't.

"Muslims have different understandings of halal food. Some have very high standards - they believe a chef in a halal restaurant needs to perform a full body washing ablution before cooking, and the restaurant mustn't sell any kind of alcohol. For some Muslims, however, as long as the raw materials are halal, the restaurant is halal," Mysterious Cabbage wrote in the article.

"And who will implement the law? Imams? Or legal authorities?" he wrote.

And as halal milk tea, halal sesame paste and even halal salt become increasingly common, others worry that these products, along with the standardization of halal food, will lead to religious segregation. They often quote Li Weihan, the head of the United Front Work Department from 1948 to 1964, who criticized this phenomenon. "It's a backward phenomenon. In current China, no ethnic group should isolate or antagonize itself from other groups," Li is quoted as saying.

In some areas in Northwest China where religious extremism is a problem, even kettles are labeled as halal. The trend worries those who oppose halal laws. "Halal food legislation, if it is successful, will make pan-Islamism a State-approved movement … Many religious understandings completely depend on the preferences of imams, and can easily be taken advantage of by extreme religious groups," an expert who requested anonymity said.

Different countries have adopted different ways of regulating halal food. In some countries where Muslims make up a significant chunk of the population, such as Singapore, religious organizations are responsible for regulating and authorizing halal food. In developed Western countries such as the UK, US and France, there are no laws on halal food since it is considered a religious issue, with halal certification generally managed by NGOs.

But religious slaughter, which some argue causes animals unnecessary suffering, has long been debated in these countries. Halal slaughter involves slitting an animal's throat with a surgically sharp instrument. Several countries, including Denmark and Switzerland, have issued laws banning halal slaughter.

An unnamed expert from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region said China should first consider its national conditions. "China isn't a theocracy, nor is it a Western secular state, but an atheist country where religious freedom is granted and every ethnic group and religion live peacefully and equally together. A halal food law doesn't suit China's conditions," he said.

He said the separation between politics and religion is the basis if any country wants to ascend to prosperity. "None of the five Muslim countries in Central Asia have halal food laws. Nor have any developed Western countries adopted such a law."

Phoenix Weekly - Global Times

Newspaper headline: Halal holdup