Villagers living near Vietnam border are still haunted by war’s legacy

Decades after China's war with Vietnam, occasional explosions that cost villagers legs, arms and even their lives are a painful reminder of the war's legacy. While some have taken it upon themselves to clear mines placed near the border by the Vietnamese and Chinese militaries, the army's mine-clearing operations continue after a 16 year break.

Wang Kaixue dismantles a landmine. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

At dawn, Wang Kaixue set off for a field that no other villager dares to stand on. It lies four kilometers away from his home in Balihe village in Yunnan Province, near the border with Vietnam.

This field is fallow and has become Wang's personal battleground because of the thousands of landmines that are buried in the area.

Upon arriving at the no-mans land, Wang, 46, left his cellphone on the edge of the minefield, and walked in with only a sickle in his hand.

On the steep mountainside, landmines and debris are easily spotted sitting on the ground. Instead of going straight for the visible mines, Wang stopped several meters away. Using the back of his sickle to gently push aside the soil under his feet layer by layer, he uncovered a landmine.

Wang then swiftly dismantled the deadly device. "The landmine that you can see is only a lure. Those buried around it are deadly," he said.

Wang describes removing mines as "performing surgery." A farmer who only finished two years of elementary school, Wang told the Global Times that he taught himself how to disable mines.

Of the 48 households in his village, 27 have had family members crippled or killed by landmines in the past three decades.

Balihe, in southeast Yunnan's Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, was one of the major battlegrounds during a series of conflicts China had with Vietnam from 1979 to 1990.

According to Yang Dekun, an official with the Wenshan civil affairs bureau, more than 100 border villages are still haunted by landmines and there are fresh casualties every year.

Wang Kaixue uses a sickle to push aside the soil. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

Personal mission

Over the course of little more than a decade, over 1.3 million landmines and 480,000 other explosives were buried by the Chinese and Vietnamese militaries in Yunnan. Across the region, there were 161 minefields, which occupied 289 square kilometers.

After two major mine-sweeping operations in the 1990s, all but 48 fields were removed. Now, there are around 70 square kilometers that are still dangerous and about 470,000 mines still buried, reported the Southern Weekly.

Wang vividly remembers how his father was killed by a landmine in 1981 when he was only 10 years old. He dropped out of school the day his father died.

"The lower parts of my father were all gone. I have hated landmines since then. But I was too young to do anything about it," he said. In 1986, when he was herding cows with his uncle, the two stumbled across a mine. His uncle lost a leg, while Wang only suffered minor injuries.

When he reached his 20s, he began to collect mines and study how they are put together. "If you are willing to use your brain and explore man-made stuff, you will learn how to dismantle it," he said.

In addition to his hatred of mines, Wang told the Global Times that another major incentive for him to face this danger is clearing the land.

"I'm a farmer. Farmers have strong feelings toward land. The land which is covered with landmines is so fertile that I can't just leave it wasted," Wang said.

He spent five years collecting and studying mines before going on his first clearance mission in 1994. Though there were other people in the village who wanted to learn how to disarm mines, he was unwilling to teach any of them.

"It's hard for others to imitate me. It needs some natural talents. Also, landmines are dangerous, I don't want the younger generation to take a risk," he said, adding that he hasn't been hurt on a mission yet.

According to him, every year he has removed at least 800 mines. He burns them afterwards. "Nothing grows where the mines are burned," he said.

Wang has cleared 130 mu (8.67 hectares) so far and has planted pear trees in the minefields, which he hopes will help his sons in the future. His boys are now working away from the village.

"I will stop my mission when I reach 50, as my eyesight will start to get worse and this will make my work dangerous," he told the Global Times.

A sign in Laoshan Mountain indicates a minefield is nearby. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

Broken villages

Laoshan Mountain, about 100 kilometers away from Balihe, was another main battleground in the Sino-Vietnamese War. In the mountain's village, 26 villagers have been injured by landmines.

While signs with skulls painted on them which were erected during the army's mine-sweeping operations clearly indicate which areas are mindfields, Laoshan resident Pan Yunting said that villagers still go into these dangerous areas to forage for herbs or collect firewood.

Around noon, Pan Yunting usually rests at home, waiting for his wife who works in the mountains to return.

His right leg was amputated after he was injured by a mine in 1995. He was chopping bamboo in the mountains when an explosive detonated due to a landslide.

Now he rests at home when it gets too hot, to avoid the sweat making his wound worse.

"Every day when my family members go out to work in the mountains, I feel worried. I feel relieved when they return home safely," Pan Yunting, 51, told the Global Times.

Pan's family grows tea in the mountains. They make about 1,000 yuan ($153) a year selling it.

Because he was disabled by a mine, the government gives him 2,560 yuan a year.

"I can't go somewhere else to work. I'm disabled and no one wants to hire me. Also, I've lived here for a long time, I don't want to move," he said.

Pan's younger cousin, Pan Yunxing, whose arm was amputated after he was injured by a mine, said that because many areas are off-limits, they have less land to farm. "Every time I go up into the mountains, I feel afraid," he said.

Pan Yunxing's son is his pride and joy because he is now at college in Wenzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province.

Like in villages all over China, Laoshan's young people are abandoning farming and looking for work in the country's cities.

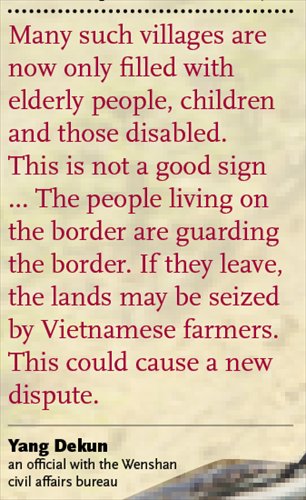

"Many such villages are now only filled with elderly people, children and those disabled. This is not a good sign," Yang said. "The people living on the border are guarding the border. If they leave, the lands may be seized by Vietnamese farmers. This could cause a new dispute," said Yang.

Pan Yunting sits in front of his home, who has an artificial leg. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

Army efforts

From 1992 to 1994, the PLA conducted its first mine clearance mission, which at that time was somewhat experimental. From 1997 to 1999, the second clearance mission was performed and the third mission began in November last year. Jiao Zhixin, an instructor with one of the four mine sweeping teams, told the Global Times that this will be the army's last mine clearance effort.

"Compared with our previous two operations, this time we will focus more on land that civilians need to farm and use. Also, we will work on the areas that are closer to the border," he said.

Jiao's team lives near Balihe village and they have cleared an area of 2 square kilometers so far. They make use of modern techniques, such as using drones to investigate minefields. "Before we depended on our eyes, but now with drones, we can have a thorough idea of the minefield's conditions," he said.

But Jiao noted that due to the region's mountainous terrain and dense vegetation, many of the army's new high-tech devices can't be used and are hard to move around.

"Besides, aside from mines, there are many other explosives like grenades and shells left on the ground. They make the mission even more dangerous," he said.

The mission - which involves 400 soldiers - is expected to be completed by 2017.

Calling for help

Balihe local Zhou Daocong said that he hopes his son will return from the city he works in one day.

"They can't make much money working outside and living costs are high in the city. I want him to return. We can work in the areas that are relatively safe," he said.

Zhou's right leg was amputated because of a mine in the 2000s. "I don't hate mines. Hatred has no meaning. I want a peaceful life," he said.

Pan Yunfa, 38, a village secretary in Laoshan, said that as the village slowly empties the border will become more vulnerable.

"The border need guards. But it's difficult for villagers to make a living here through farming. I think the government should attract investment and companies to the area and provide more job opportunities for us," he said.

"Besides, our village has some native products like tea, bamboo shoots and chickens. If some companies can come here to help us develop them as a brand, our living can be enhanced," he added.

Yang noted that due to inflation, government disability subsidies are not enough to cover their soaring living costs.

"But Wenshan is a poor prefecture. We are not able to give people a lot of money. I hope the central government can provide more help for us," he said.

Newspaper headline: That old home of mine