Chinese-Filipino community tries to heal rift as South China Sea spat worsens ties

Faced with economic troubles caused by increasing tensions between China and the Philippines, ordinary Chinese-Filipinos are trying to mend relations between the two nations, as memories of official discrimination linger.

A Filipino-Chinese Friendship Arch in Manila's Chinatown. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Meah Ang See remembers being told "go back to your country" a few years back by some Filipinos, at a time when there was a lot of discrimination against the country's ethnic Chinese community. She felt amused, not angry.

"I was born here, I'm a Filipino. I can't even speak Chinese," she said.

She is the managing director of Bahay Tsinoy, a museum dedicated to the history of the Chinese-Filipino community. The museum was established in the Kaisa-Angelo King Heritage Center building in Manila and documents the history, livelihood and contributions of the Chinese in the Philippines. It has become a symbol of ties between the two countries, attracting officials, scholars and tourists from both nations.

The kind of ethnic tension see faced has a long history in the Philippines and these problems have resurfaced once again as disputes over territory in the South China Sea have escalated between the two countries in recent years.

However, many prominent figures in the community have started trying to repair the friendship between the two countries, starting with introducing ethnic Chinese to ethnic Filipinos to foster new relationships.

A child jumps up in front of a Chinese-owned store that sells feng shui charms, crystals and healing stones in Manila. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Past of discrimination

The Chinese community in the Philippines has faced heavy discrimination historically, said See.

Chinese started migrating to the Philippines as early as the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). At that time most Chinese in the archipelago were food vendors or ran small businesses, but during the Spanish colonial period there were strict laws that limited what kinds of jobs ethnic Chinese people could do in the country.

Under American rule, an anti-Chinese law was passed which meant Chinese-Filipinos were banned from migrating to the US.

Even after the Philippines became independent, this anti-Chinese mindset was still there. People in the Chinese community lived very separate lives from ethnic Filipinos, with their own shops, restaurants, hospitals and schools.

This social separation was mirrored at the official level.

"Back then, when Chinatown caught on fire, the Philippine government fire department would not send a fire truck," See said. "They said, 'You live in your own town, you should put out your own fires.'"

Gradually, fire associations were established in Chinatown and the community equipped its own fire trucks to make sure that they could keep themselves safe. The tradition still exists - when the Global Times reporter visited Binondo, where the Manila Chinatown is located, there were many fire trucks that had the words "fire association" written in Chinese on them.

Some Chinese-Filipinos have decided to fight against this discrimination. Among them is Tessy Ang See, the founder of Bahay Tsinoy.

The museum was established in 1999. The word "Tsinoy" is a local colloquial term meaning "Chinese-Filipino."

In 1975, the Philippine government finally gave citizenship to Chinese-Filipinos. While the standing of the community has improved, discrimination has not totally been eradicated.

With all the history of discrimination and insecurity, the Chinese community today seeks to avoid conflicts and hopes to improve relations, so there can be a stable environment for exchanges and business.

A Jeepney (a popular means of transportation in the Philippines) rides through the streets of Manila's Chinatown. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Affecting the common people

Since disputes over the South China Sea escalated in 2012 between China and the Philippines, Chinese-owned businesses have taken a hit. There were protests in 2012 after Chinese and Filipino ships stood off at Huangyan Island. Many Chinese-Filipinos, whether or not they care about politics, have suffered along with the relations between the two countries.

Carlos Chan, CEO of food and beverages producer Oishi in the Philippines, told the Global Times previously that after 2012 many Chinese tourists stopped coming to the Philippines. As a result, the country's tourism and food industries took a hit. Hotels, restaurants and tourism agencies received less income, and many Chinese-Filipinos worked in these industries at the time due to their links with China.

Huang Dongxing, a Chinese-Filipino media correspondent, said he has tried to hold cultural and media exchanges between the two countries, but unfortunately his plan to start a Chinese-language TV station in the Philippines was kiboshed by the 2012 protests.

Herman Tiu Laurel, the host of the Manila-based Global News Network (GNN), told the Global Times he got into a quarrel with a reader on Facebook over the GNN's representation of China and issues related to the South China Sea disputes.

"After months of arguing, he said to me, 'You go back to your country, you go back to China!' and I said to him, 'My home is here in Asia, but where are you living? You live in the US!'" Laurel said.

Besides people who have business links with China, people of Chinese ancestry who are living in the Philippines are hoping for improved relations.

A Chinese-Filipino woman, who preferred to remain anonymous and runs a pharmacy in Manila's Chinatown, said she's been in the Philippines for more than 20 years and considers it her home.

She wants the relationship between China and the Philippines to improve, she said, adding that this is a wish shared by many in the Chinese community here, because they have family, friends and businesses in both countries.

Bridging understanding

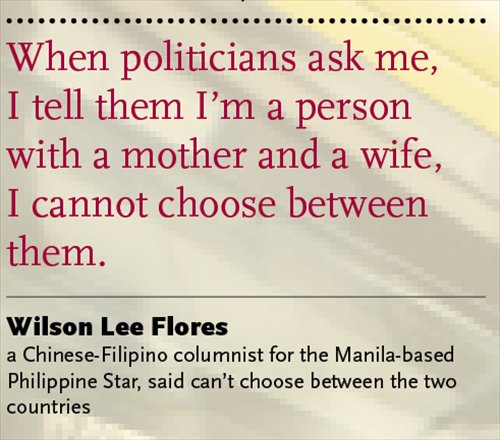

Many Chinese-Filipinos are starting to host events, exchanges or trying to improve the impression people in both countries have of each other. Wilson Lee Flores, a columnist for the Manila-based Philippine Star and a well-known figure in the Chinese community, said no matter which way relations between the two countries go, the ordinary people will always be the ones that are most affected.

He took himself as an example, saying he can't choose between the two countries, and that's why he hopes relations will keep improving, so that people don't need to choose.

"When politicians ask me, I tell them I'm a person with a mother and a wife, I cannot choose between them," he said.

Oishi has held a number of cultural exchanges, inviting Philippine scholars, media or businessmen to China and vice versa. He told the Global Times that every time people go on these trips, they feel amazed about the things they see and what they learn.

Flores has just come back from such a cultural exchange to Shenzhen, South China's Guangdong Province. Last week, he spoke on a TV show about what he saw, to a mostly ethnic Filipino audience. He talked about the high-technology centers in Shenzhen, about the factories, and businesses there and the city's prosperity.

Bahay Tsinoy is also playing an important role in growing intercultural links. Often Chinese and Filipino scholars, media and tourists come to visit the museum.

Public opinion and media presentationis another area people are pushing for change in.

Chito Sta. Romana, former ABC bureau chief in Beijing and now the president of the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies, said he holds the media in the two countries accountable for inflaming people's emotions.

"In 2012 there were some protests, but they were very small, they've been blown out of proportion in the media," he said.

George T. Siy, secretariat of the Anvil Business Club and chairman of the Association of Young Filipino-Chinese Entrepreneurs, said he is working on a project that can hopefully change how media and people view each other.

He hopes to establish an institute that hires professors and media analysts to research China, and publish reliable reports.

"The media in this country like to quote 'institutes' and professors," Flores said. "Many times the institutions are biased when it comes to China. So why not establish our own institute with more balanced research and let the media quote that?" he said.

"The view on the relationship has always been on the positive side by the people. Our relationships with China are mostly with the people," See said. "For example, there are a number of Tsinoy businessmen who have opened factories in China. The biggest is Carlos Chan of Oishi."

Flores said he is happy to see all the exchanges going on between the two countries and he hopes the Chinese community can play a bigger part in this.

"We are faced with a great task, we have an opportunity to be the bridge," he said.

Rose Quito, an ethnic Filipino that owns a cigarette and beverage business based in Pasay City, southwest of Manila, told the Global Times on Monday that she is not that up-to-date on the South China Sea issue because she thinks it's a matter between the Philippine and Chinese governments.

Quito said she is more concerned with her own life, as well as how she will be treated if she would travel to China, a trip that she hopes she can take in the near future.

When walking on the streets or taking taxis, the Global Times reporter was often asked by ordinary people "Where are you from?" When the reporter replied "China," she was met with a positive response. Locals told her they would like to visit the Great Wall and the Forbidden City, and that they think China is a successful country.

Newspaper headline: Caught in the crossfire