An interview with Chinese children’s book artist Zhu Chengliang

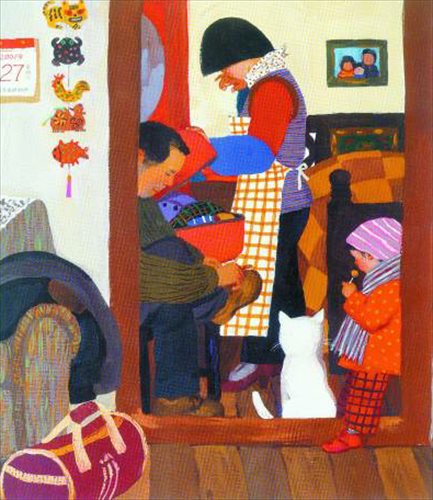

The bittersweet story of a migrant worker returning home to his wife and young daughter for a heartbreakingly brief holiday, Chinese children's book New Year's Reunion has resonated with readers from various regions and socio-economic backgrounds across China, where an estimated 200 million migrants must leave their provincial homes to work year-round elsewhere.

Despite this "floating population" being a phenomenon relatively unique to China, New Year's Reunion also touched the hearts of countless international families across the world, where it has been translated into multiple languages and won numerous awards since it was first published in 2008.

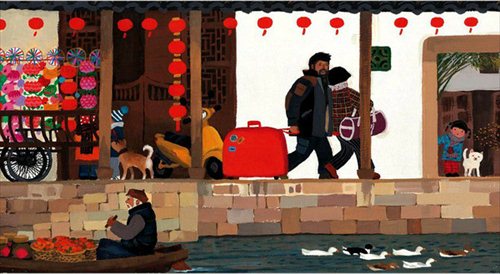

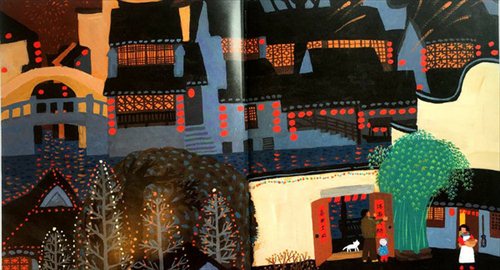

Chinese and Western readers alike agree that much of the book's success should be attributed to its prize-winning illustrator, Zhu Chengliang, who transformed author Yu Liqiong's sparse text into a poignant visual narrative rich with the evocative imagery of China's rural villages.

Zhu was born in 1948 in Shanghai, but spent his early adulthood as a zhiqing (educated youth) in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). There he developed an affinity for China's peasantry that carried over into his long career as an illustrator, preferring traditional artistic mediums and stories with rustic settings.

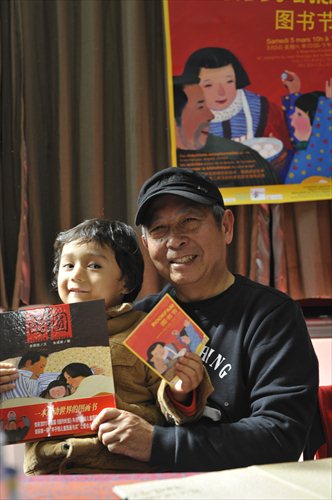

Though he is now semi-retired, Zhu can't help continuing to dabble in the arts. He recently attended a children's book fair in Shanghai, where the Global Times managed to pull him away for a few minutes from a queue of expat parents and toddlers eager for an autograph to discuss his background, his methodology and his approach to the genre.

Zhu Chengliang with a young fan at a Shanghai children's book fair Photo: Tom Carter/GT

GT: Who were your favorite illustrators growing up and how did they influence you?

Zhu: I grew up in the 1950s in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. At that time there were no high-level art exhibitions. We only knew our own local artists. He Youzhi (1922-2016), also born in Shanghai, was my most admired artist of lianhuanhua (hand-sized picture books). His careful observations of life depicted the ordinary people of Chinese society, the laobaixing. There was a children's library across the street from my primary school. I often went there to read lianhuanhua. At that time, my understanding of art was only from these books.

GT: You attended the Nanjing University of the Arts as an oil-painting major, but were sent down to the countryside in the 1960s. Did that experience impact your artistic style?

Zhu: Yes, it feels more familiar when I draw rural-life subjects for my picture books, especially when it's about villages in the Jiangnan (south of the Yangtze River) regions. But the difference between South and North China artistic styles is not very obvious to the average reader, so I don't put myself in any specific category.

GT: Do you use different mediums to evoke different feelings in each book? Describe your artistic process and the evolution of your style.

Zhu: Most of my picture books were written by different authors. So for different stories from different writers, the styles and materials of my illustrations were always different. I use the content of the story to come up with different artistic techniques (e.g. wood engraving, watercolors or gouache). None look the same. I try to adapt to the evolving content. Being picturesque is very important to a narrative. The books I choose, in addition to having a good story, have a sense of painting.

GT: New Year's Reunion has been translated into several languages. What about this book has affected so many cultures?

Zhu: Because the warmth of human nature goes beyond national boundaries, regardless of ethnic groups.

GT: December Porridge is set in the countryside, but hanging up dried meats and fish is still a common sight in urban Shanghai every winter. When you drew these scenes years ago were you conscious that many of these details would still exist today?

Zhu: Maybe it's becoming less common in big cities, but salting fish and meat will always be a traditional Chinese custom.

GT: Sweet Orange Tree is about young boys in the countryside getting into mischief. Do you think today's generation of Chinese children have lost that sense of freedom and exploration?

Zhu: Childhood in China differs between regions and between urban and rural areas. And most kids from the city are from only-child families, so they can't possibly have the same upbringing as children in the countryside.

GT: To draw New Year's Reunion, you returned to a village that you visited 40 years ago. For Flame, you went all the way to Lugu Lake in Yunnan. Do you travel every time you start on a new book?

Zhu: Yes, I go traveling first and collect examples of that place. It's the best way to turn words into pictures. Even if a book's text is brushed lightly, the picture must always be solid. Details are very important to me. For example, the rabbit lamp in New Year's Reunion was an important part of Spring Festival when I was young. Most of the pieces I have drawn are based on real subjects, real experiences.

GT: What are your thoughts on the lack of ethnic diversity in children's books by the global publishing industry, and the future of print picture books given the rise of digital apps and e-books?

Zhu: Printed picture books will always be popular. Parent-child reading begins with the picture books that they can hold in their hands. Every generation needs that and then passes it on to the next. Chinese picture books are pretty diversified now and our domestic artists are rising. Even though I'm older and slower now, I still hand-draw all my illustrations. Our spring is coming.

Chinese children's book artist Zhu Chengliang's illustrations Photo: From the Internet

Chinese children's book artist Zhu Chengliang's illustrations Photo: From the Internet

Chinese children's book artist Zhu Chengliang's illustrations Photo: From the Internet

Newspaper headline: Illustrating China