DNA research uncovers Dead Sea Scrolls mystery

Source:AFP Published: 2020/6/3 18:48:40

DNA research on the Dead Sea Scrolls has revealed that not all of the ancient manuscripts came from the desert landscape where they were discovered, according to a study published on Tuesday.

The parchment and papyrus scrolls contain Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic and include some of the earliest-known texts from the Bible, including the oldest surviving copy of the Ten Commandments.

Research on the texts has been ongoing for decades and in the latest study, DNA tests on manuscript fragments indicate that some were not originally from the area around the caves.

"We have discovered through analyzing parchment fragments that some texts were written on the skin of cows and sheep, whereas before we thought they had all been written on goat skin," said researcher Pnina Shor, who heads the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) project studying the manuscripts.

"This proves that the manuscripts do not come from the desert where they were found," she told AFP.

The researchers from the IAA and Tel Aviv University were unable to pinpoint where the fragments came from during their seven-year study, which focused on 13 texts.

The Dead Sea Scrolls date from 3BC to AD1.

Many experts believe the manuscripts were written by the Essenes, a dissident Jewish sect that had retreated into the Judaean desert around Qumran and its caves. Others argue that some of the texts were hidden by Jews fleeing the advance of the Romans.

"These initial results will have repercussions on the study of the life of Jews during the period of the Second Temple" in Jerusalem that was destroyed by the Romans in AD70, said Shor.

Such archaeological research remains a sensitive subject in Israel and the Palestinian territories, as findings are sometimes used by organizations or political parties to justify their claims to contested land.

Beatriz Riestra, a researcher who took part in the study, pointed to "differences at the same time in the content and the style of calligraphy, but also in the animal skin used for the parchment, proving they are of different origin."

In total, some 25,000 parchment fragments have been discovered and the texts have been continuously studied for more than 60 years.

"It's like piecing together parts of a puzzle," said Oded Rechavi, a professor who led the Tel Aviv University team.

"There are many scrolls fragments that we don't know how to connect, and if we connect wrong pieces together it can change dramatically the interpretation of any scroll," he said.

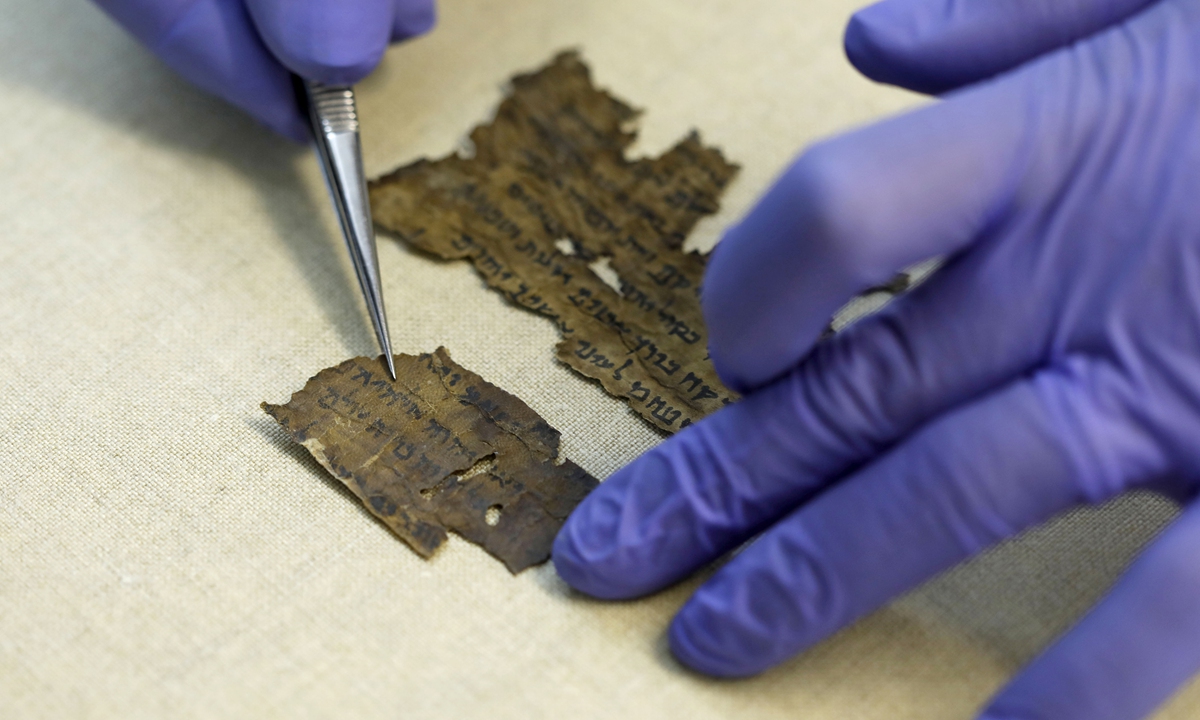

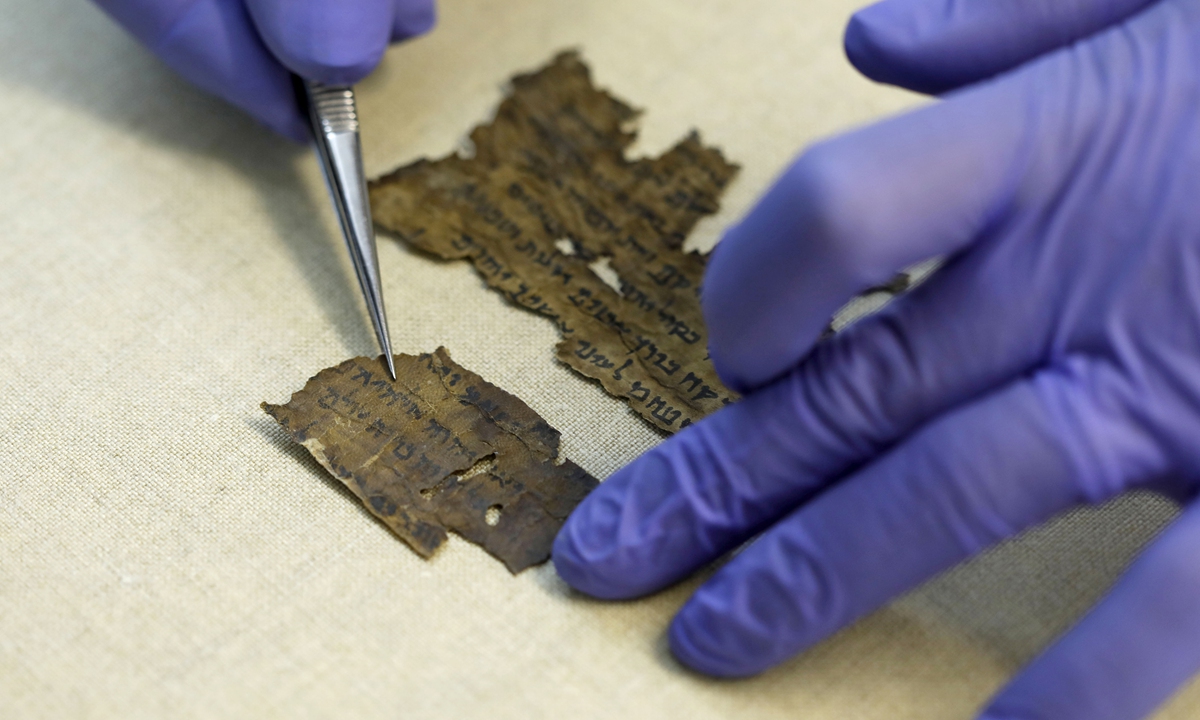

A conservator of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) shows fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls at their laboratory in Jerusalem. Photo: AFP

Numbering around 900, the manuscripts were found between 1947 - first by Bedouin shepherds - and 1956 in the Qumran caves above the Dead Sea that are today located in the Israeli-occupied West Bank.The parchment and papyrus scrolls contain Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic and include some of the earliest-known texts from the Bible, including the oldest surviving copy of the Ten Commandments.

Research on the texts has been ongoing for decades and in the latest study, DNA tests on manuscript fragments indicate that some were not originally from the area around the caves.

"We have discovered through analyzing parchment fragments that some texts were written on the skin of cows and sheep, whereas before we thought they had all been written on goat skin," said researcher Pnina Shor, who heads the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) project studying the manuscripts.

"This proves that the manuscripts do not come from the desert where they were found," she told AFP.

The researchers from the IAA and Tel Aviv University were unable to pinpoint where the fragments came from during their seven-year study, which focused on 13 texts.

The Dead Sea Scrolls date from 3BC to AD1.

Many experts believe the manuscripts were written by the Essenes, a dissident Jewish sect that had retreated into the Judaean desert around Qumran and its caves. Others argue that some of the texts were hidden by Jews fleeing the advance of the Romans.

"These initial results will have repercussions on the study of the life of Jews during the period of the Second Temple" in Jerusalem that was destroyed by the Romans in AD70, said Shor.

Such archaeological research remains a sensitive subject in Israel and the Palestinian territories, as findings are sometimes used by organizations or political parties to justify their claims to contested land.

Beatriz Riestra, a researcher who took part in the study, pointed to "differences at the same time in the content and the style of calligraphy, but also in the animal skin used for the parchment, proving they are of different origin."

In total, some 25,000 parchment fragments have been discovered and the texts have been continuously studied for more than 60 years.

"It's like piecing together parts of a puzzle," said Oded Rechavi, a professor who led the Tel Aviv University team.

"There are many scrolls fragments that we don't know how to connect, and if we connect wrong pieces together it can change dramatically the interpretation of any scroll," he said.

Posted in: MID-EAST